Peter Biar Ajak thought he was meeting with arms dealers in a Phoenix warehouse in late February.

He’d traveled across the country — Ajak lives in Montgomery County — to try on a bulletproof vest and helmet, inspect weapons and handle two different rifles. The supplies would be shipped to South Sudan soon, and Ajak had plans to spark a revolution.

“I’ve got to be leading from the front, not the back,” Ajak said during the inspection.

But Ajak, an internationally recognized peace activist, was not meeting with arms dealers. He and his co-defendant were meeting with undercover agents from the U.S. Department of Defense and Homeland Security Investigations. They are accused of conspiring to violate sanctions and smuggling goods from the United States. Federal prosecutors allege Ajak sought to supply weapons to military generals in South Sudan, wage an armed effort to topple the government and seize power.

Ajak has pleaded not guilty and is detained in Arizona.

This story of how Ajak, now 40, came to face federal charges in a country that twice welcomed him as a refugee is reconstructed from court documents, including a warrant and affidavit for a search of his Maryland home, public remarks, media reports, social media posts and other sources.

Before facing these charges, Ajak lived a complicated and at-times tragic life. He’s been a refugee and trained as a child soldier. He’s been a student at Cambridge, an economist for the World Bank and a fellow at the Harvard Kennedy School. And he was made a political prisoner in his home country.

In an emailed statement, Ajak’s Arizona-based attorney, Kurt Michael Altman, called Ajak “a remarkable man with a remarkable history.”

“He [Ajak] is an idealist who believes peace is the answer. He looks forward to his day in court and is confident that those who believe peace and freedom are the paths to prosperity will have his back,” Altman wrote.

Early life

Ajak was born just months after the Second Sudanese Civil War broke out in 1983. While his village stayed untouched by the war for a few years, there was an attack in 1989. Ajak and his family walked hundreds of miles to a refugee camp in Ethiopia.

While there, Ajak’s father enrolled him in the “Red Army,” a group of refugee children recruited by the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement.

He was at the Ethiopian refugee camp, learning Marxist ideology and training in survival techniques with the Red Army, for two years.

In 1991, the government that supported the Sudanese refugees collapsed, and Ajak and his family returned to Sudan. The next year, he arrived at a refugee camp in Kenya, where he remained until 2001.

Life in the U.S.

The Lost Boys of Sudan began arriving in the United States in late 2000. A 16-year-old Ajak arrived in Philadelphia in January 2001. He carried with him nothing but immigration papers declaring him a refugee and a chest X-ray that proved he did not have tuberculosis, according to the Philadelphia Inquirer.

Ajak began working to catch-up with his peers in school — and worked part-time loading packages to earn money to send back to his mother.

He did well in school and attended LaSalle College. After graduating in 2007, he enrolled in the Harvard Kennedy School and earned a master’s degree.

While still a student, Ajak told the Kennedy School magazine he was eager to return to Sudan. He said he might work for a defense ministry in a hypothetical South Sudan — the country would not become independent until July 2011.

Return to Sudan

After graduating in 2009, Ajak moved back to Sudan where he worked for the World Bank until South Sudan won independence in 2011. Salva Kiir Mayardit became president when the country was formed, and there have not been elections since.

Ajak entered government work after the country’s independence as a senior advisor to the Minister of National Security.

“Being in South Sudan, you’re part of building something new,” Ajak said in a 2016 VICE Sports documentary. “If I succeed in making even a small difference in South Sudan, it’s much more meaningful to me than whatever I would have done in the United States.”

He was part of the VICE documentary because he once organized wrestling tournaments to bring people together in Sudan.

His time in government ended within a few years — the minister he advised was fired, so Ajak pursued a doctorate at the University of Cambridge.

When another civil war broke out in South Sudan, Ajak began building the South Sudan Young Leaders Forum, a group that encouraged older political leaders to exit public life. He became increasingly vocal and critical of the government.

Political prisoner and return to the U.S.

On July 28, 2018, Ajak was arrested at Juba International Airport in South Sudan. He said he was not initially told why and was detained in the National Security Service’s infamous “blue house.”

Ajak later recalled hearing fellow prisoners scream as they were tortured, and the uncertainty of whether he would be next.

After months in prison, he was brought before a judge and accused of crimes against the state. He was convicted on June 11, 2019, and sentenced to two years at Juba Central Prison.

Ajak’s arrest and conviction drew international outcry. He was pardoned in January 2020 and moved to Kenya for medical treatment and a reunion with his family.

Over the summer, Ajak and his family fled to the United States. The same president who had pardoned him had ordered Ajak kidnapped or murdered, Ajak said. He was, for the second time, a refugee.

He and his family eventually moved to a home in Montgomery County.

Ajak continued his political advocacy, and has been a fellow at the Belfer Center, a fellow at the National Endowment for Democracy and adjunct faculty at the Africa Center for Strategic Studies of the National Defense University.

In 2021, he spoke at the Summit for Democracy hosted by the United States. While speaking about his experience as a political prisoner, Ajak said freedom “does not come on its own.”

“It requires people willing to fight for it, to defend it, to risk their lives for it,” he said.

Revive South Sudan and criminal charges

In a manifesto posted Aug. 14, 2023, Ajak announced the formation of the Revive South Sudan Party. In the video, Ajak said the party envisioned a peaceful future for South Sudan. Inquiries from The Baltimore Banner to the party went unanswered.

Ajak began speaking with the undercover agents in the federal investigation that would lead to his indictment months later, on Nov. 2, 2023. The following narrative that lays out the allegations against Ajak are from charging documents, a search warrant for his Bethesda home, a criminal complaint and detention documents.

On that day, Abraham Chol Keech, a co-defendant in the case, introduced Ajak to undercover federal agents he’d been speaking with. Keech described Ajak as someone who was not initially convinced that violence was the right approach to changing things in South Sudan, but had since changed his mind.

Days later, on Nov. 8, Ajak said he was looking for “basically a coup” of the South Sudanese government, and that he wanted to “knock it over and rebuild a new country.”

Ajak said he would be the new head of government and prime minister, and that he has “the backing of the State Department, implicitly.”

A State Department spokesperson said the United States does not support violent or undemocratic change to the government in South Sudan or elsewhere in Africa.

There were multiple times during the course of the investigation that one of the undercover agents brought up sanctions against South Sudan and mentioned the scheme to move weapons into the country was illegal.

Ajak or Keech dismissed those concerns. Ajak said sanctions would be “lifted immediately” after the coup.

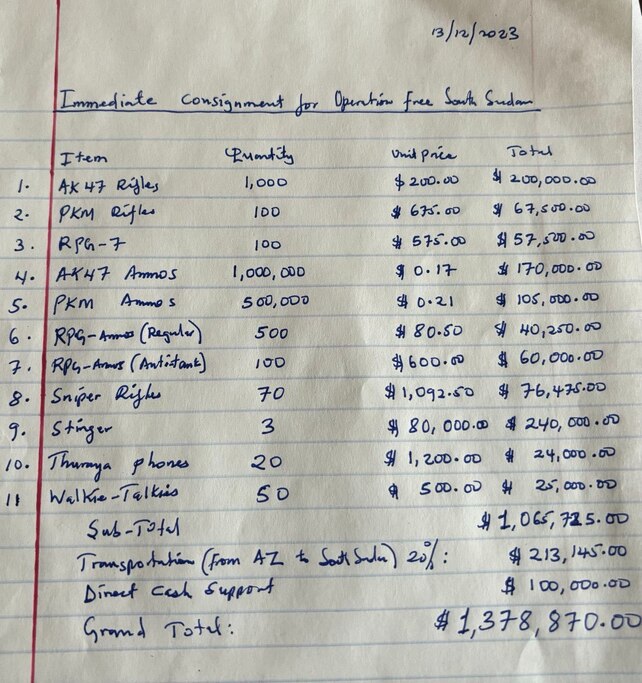

In late December 2023, Keech sent a photo to Ajak and one of the undercover agents showing a handwritten list of weapons labeled “Immediate consignment for Operation Free South Sudan.”

The list included 1,000 AK-47 rifles, 3 Stinger missile systems, 100 RPG-7 rocket launchers, 70 sniper rifles and more than 1 million rounds of ammo. The plan would involve moving the weapons from Arizona to another African country not named in court records, disguised as humanitarian aid to avoid sanctions.

From there, the weapons would move into South Sudan.

On Christmas Eve, Ajak posted a video message and called for 2024 to be the “year of freedom when the people of South Sudan will take their country back.”

Final stages

On New Year’s Eve, Ajak made an address under the Revive South Sudan Party again. He said 2024 would be a year to “seize our country” and warned that anyone who rules by the sword can also die by the sword.

“2024 is a year we are not joking,” Ajak said in a video posted on YouTube. “We are prepared to act in a significant manner.”

He began meeting with potential financiers, according to a criminal complaint and an affidavit attached to a search warrant for Ajak’s home. Ajak left his Bethesda home and traveled to New York City, where he checked into a meeting called “South Sudan Strategy Session” at the office of an unnamed law firm on Jan. 24, 2024.

The next day, Ajak messaged one of the undercover agents and said he wanted the weapons in South Sudan by March 30. He said he needed a helmet, bulletproof vest and rifle for his personal use.

“Because I’m obviously going to be leading this mission,” Ajak said, he needed “something really dependable and something that is easy and something that is pretty bad ass.”

On Feb. 8, Ajak met with two people in a condo building on 61st Street in New York. The next day, he told one of the undercover agents, “We are getting the funding” and arranged a payment schedule after raising the concern that if he paid “all the money and then you don’t deliver, then we are fucked, right?”

Over a series of meetings and calls, Ajak, Keech and the undercover agents arrived on a final plan and a contract was drawn up. The plan involved a fake invoice for “consulting services” related to “human rights” in refugee camps in South Sudan.

On Feb. 16, one of the undercover agents sent the weapons contract and the “fake” consulting contract. The plan called for shipping the weapons via air cargo from the U.S. to Africa, then moving them on a truck convoy into South Sudan.

By then, the weapons order had ballooned to include 200 rocket launchers, 10 Stinger missile systems and more than 3 million rounds of ammo.

They set up a payment plan. The first $275,000 cleared in the undercover agents’ bank account on or around Feb. 20. By Feb. 26, $2 million had been deposited.

Keech, Ajak, a person identified as an “associate” of theirs who is a “weapons expert,” and the undercover agents met at the Phoenix warehouse on Feb. 22.

During that meeting, where Ajak tried on armor and handled rifles, the undercover agents reiterated the illegality of shipping the weapons to South Sudan.

Ajak signed and initialed copies of the weapons contract and the “fake” contract.

The next day, Keech and Ajak agreed to travel back to Phoenix for another inspection on March 1.

Where things stand

Instead of a weapons inspection, Ajak and Keech were arrested by Homeland Security Agents in Phoenix on March 1.

After he was read his rights, Ajak said he wanted to get people to protest and anticipated a situation where the South Sudanese government would “probably shoot people down,” sparking “a revolution.”

Advocating for elections hadn’t worked, and “something different needed to be done,” he said.

Ajak admitted to signing the contracts, said he was aware of the arms embargo and said he caused the money to be transferred, according to the government’s pretrial detention memo. He said he planned to travel to South Sudan and abandon his immigration status in the United States. He said he was meant to become interim president when the current government was overthrown.

He said that he would receive $8 million in financing to establish a democracy, including $2.2 million to bribe the military.

Ajak and Keech were indicted in the United States District Court for the District of Arizona on March 6. Ajak pleaded not guilty during an initial court appearance on March 15, according to online court records.

Ajak’s attorney argued in court filings that he is not a flight risk or danger to his community. His only passport was taken when federal agents searched his Bethesda home on March 1.

A trial is scheduled for early August. If convicted on all three charges, Ajak faces up to 50 years in prison.

Comments

Welcome to The Banner's subscriber-only commenting community. Please review our community guidelines.