Medical malpractice attorney Stephen L. Snyder believed he had stumbled upon an enormous scandal: The University of Maryland Medical System’s organ transplant program was giving patients high-risk kidneys at by far the highest rate in the country, he alleged in 2018.

Kidneys in poor condition were being transplanted with high rates of failure, and at a higher clip than other similar hospitals, Snyder determined after consulting with experts. He came to the conclusion that there was “no legitimate explanation except profit over safety.”

“You are playing with fire,” Snyder wrote in prepared notes for a meeting with hospital officials.

What Snyder did next — allegedly demanding a $25 million payoff in exchange for keeping quiet about his findings — resulted in an FBI investigation and federal criminal extortion charges. The case has been pending for four years and is scheduled for trial Tuesday.

The underlying situation at UMMS that Snyder threatened to expose, however, has largely escaped public scrutiny.

At a pretrial hearing last month, federal prosecutors asked that the case not dwell on the hospital system. “The University of Maryland is not on trial,” Assistant U.S. Attorney Matthew Phelps said.

But Judge Deborah Boardman said information about problems at the hospital were relevant to Snyder’s “state of mind” as he jockeyed for a payday. The former chief medical officer targeted by Snyder, Dr. Stephen Bartlett, is among those expected to be called to testify.

In a statement, UMMS officials said that in the years since Snyder approached them, the overall number of kidney transplants has decreased “due to our refined waitlisting criteria and donor organ selection.” And data shows the percentage of high-risk kidneys being used has decreased. The hospital said its patient outcomes have improved “significantly” and that they have “more insights and resources available to guide us in these decisions.”

Legally secret medical mistakes

Not all bad outcomes involve medical mistakes. But the Snyder case provides a rare window into what happens when someone alleges serious lack of judgment or other error in the nation’s hospitals, something that John Hopkins University researchers once estimated is so significant that it may be the third leading cause of death in the nation.

Some states have made changes to increase transparency, but in Maryland the errors remain legally secret, protected by a law aimed at encouraging hospitals to report what went wrong to state regulators, who then work with the hospital on improvements — all out of public view.

Patients, or patients’ relatives, who allege serious injury also typically keep quiet about the details of serious injuries if they reach a monetary settlement with a hospital. Shepherding that process is typically an established medical malpractice lawyer such as Snyder.

Federal data shows there were 246 medical malpractice claims made in Maryland in 2023.

Malpractice cases seldom make it to court.

Those who want to evaluate the general performance of a specific hospital can turn to various rankings, consumer satisfaction surveys and, in the case of transplants, a public registry.

All of UMMS’s transplants are done at the University of Maryland Medical Center. A national database called the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients shows the center’s one-year survival rate of kidney transplant patients to be in the middle of the pack nationally. It’s an improvement, the medical center notes, but still trails those of programs at Johns Hopkins and the Walter Reed National Military Center.

Dr. David Leeser, who was chief of UMMS’s kidney transplant program until 2017, said the hospital’s “approach was to transplant as many people as you could possibly transplant” and that over the last 20 years it has been known for taking risks in order to help patients other hospitals would turn away.

“Programs that are moving the needle, and pushing the field forward, are always going to walk on a line with their outcomes compared to programs nationally,” Leeser said. “You’re taking risk, and your outcomes may not be quite as good. But you’re also getting more patients transplanted.”

Leeser, who is now chief of kidney and pancreas transplantation at East Carolina University Health, said that critics are viewing the data rigidly, and that can be misleading.

UMMS spokeswoman Tiffany Washington said transplantation is “a complex field” and that the hospital “continuously reviews and refines its processes using the latest available data.”

“As our practices evolve, our values and fundamental goals have remained the same — to save more lives in the face of a persistent organ shortage and high waitlist mortality,” she said.

Data from the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network suggests the hospital has adjusted course in recent years. The number of overall transplants has declined, while high-risk transplants — previously two or three times higher at UMMS than at Johns Hopkins Hospital — has leveled off as a proportion of them.

Snyder case, UMMS allegations

The Snyder case has already shed light on some of UMMS’s secrets.

The University of Maryland paid settlements on two cases brought by Snyder and his clients, according to court documents in his case. One client was the wife of a man who died after transplant surgery, and the other was a woman paralyzed after undergoing transplant surgery.

Snyder alleged the hospital pressured doctors to perform lucrative transplants and that quality was slipping before the chief medical officer, Bartlett, left the program in 2018 after nearly three decades, according to court documents.

The hospital has not said why he left and denied accusations leveled against the program. Bartlett declined to comment for this article.

Kidneys available for transplant are rated on a scale called the Kidney Donor Profile Index, or KDPI, which considers 10 different factors in evaluating how well a kidney is expected to work. The scale goes from 0 to 100. Over 85 considered especially high risk.

Snyder approached UMMS after meeting with a transplant recipient who had received a kidney with a KDPI rating of 97. Snyder said the kidney was also infected with several dangerous viruses, and had been rejected by 250 other institutions.

“It was a kidney that [the surgeon] said he would implant in his wife. It was a kidney that failed the first day,” Snyder wrote in his prepared presentation, now a court exhibit. “And it’s a kidney that ultimately resulted in [the recipient’s] death. And [the recipient] was healthy, not on death’s doorsteps.”

“It was a kidney that had the University of Maryland not misrepresented the status of this kidney would have never been accepted under any circumstances,” Snyder continued. “No one in their right mind would have accepted this kidney and [the recipient] paid for it with his life. [The recipient] accepted this organ because of the clear and intentional misrepresentation and omission of facts.”

Asked whether UMMS concealed the condition of the organs from the patients, Leeser did not directly respond, instead saying that getting any transplant was a better outcome than dialysis. “A 20-year-old Chevy Silverado may not look great but if well-maintained, it will get you where you need to go,” he wrote in an e-mail. “Isn’t being above ground the point?”

Another Snyder client suffered spinal paralysis during a pancreas transplant. Dr. Antonio Di Carlo, of Temple University Hospital, consulted for Snyder on that case and concluded that UMMS found the patient too high-risk because of coronary disease, but still preformed the pancreas transplant in January 2017.

Moreover, Di Carlo said, data showed UMMS doctors were displaying poor judgment and taking excessive risks.

Another consultant, Dr. Jesse Schold, who previously oversaw outcomes monitoring and quality evaluation in kidney transplantation at the Cleveland Clinic, told Snyder that candidates for kidney transplants at UMMS had a 38% higher risk for mortality than expected for such a program, and that its use of low-quality, high-risk kidneys was almost twice the national average.

The program’s problems were known within medical circles, Di Carlo said, and provided names of surgeons who were attempting to leave. He added that he knew of one surgeon who was hastily promoted due to the vacancies. So many were leaving or trying to leave that DiCarlo said he had difficulty keeping track of them. Snyder’s presentation asserted that “six board certified doctors are gone, two demoted.”

Snyder put much of the blame at the feet of Bartlett, who is now affiliated with the University of Illinois.

A post-Bartlett change

A person familiar with how the transplant program was run, who was granted anonymity to speak freely, said they agreed with Snyder’s assessment that there was overuse of deficient organs, but said that soon after Bartlett left, the pendulum swung the other way due to the costs of such transplants.

“A bad outcome does translate into higher costs in a lot of cases,” the person said.

“It’s all about money,” they continued. “They took a 180. But neither approach is really in the best interest of patients.”

Another person familiar with the program, who also spoke anonymously, shared views more in line with the hospital. One described the heightened use of organs as a mission to save the lives of more, often sicker, patients, and the shift to fewer transplants as an issue with budgeting for hospitals in the state generally.

Hospitals in Maryland have limits on how much money they can make from patient care, so they can do only so many costly transplants. State regulators, however, say no hospital has brought the issue to their attention.

It’s also unclear if any quality issues persist in UMMS’s transplant program. The federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services is supposed to recertify programs every five years; The last time the agency evaluated the medical center, however, was in 2015.

CMS found deficiencies, including a lack of criteria to show if living kidney donors were suitable and if donor and recipient blood types properly matched. The hospital submitted a plan to correct the issues. Another survey of the program is pending, according to a statement from CMS.

Snyder had accused the hospital of misleading patients who were vulnerable because of their health status and limited educational background, while withholding critical information from them. He had a text message from Bartlett acknowledging the hospital was “on [the] hook for fraud and punitive damages,” according to court documents.

Snyder vowed to roll out a press blitz to expose the hospital and drive patients elsewhere. He name-checked high-profile cases from recent years involving other area hospitals.

Then he pitched himself as just the man to solve a PR crisis like the one he was threatening to create.

“The consulting agreement would provide that Snyder would defend future cases against the hospital,” a legal expert consulting for Snyder wrote in a document included in court records. “In 2018, there was a likelihood of multiple additional cases and no attorney knew the strengths and weaknesses of these types of cases better than Snyder.”

Snyder said he could work for them as much or as little as they wanted, joking that he could serve as a janitor. The hospital went to the FBI, which surreptitiously recorded him. Snyder was first brought up on disciplinary charges by the Maryland Attorney Grievance Commission, then later indicted by federal prosecutors.

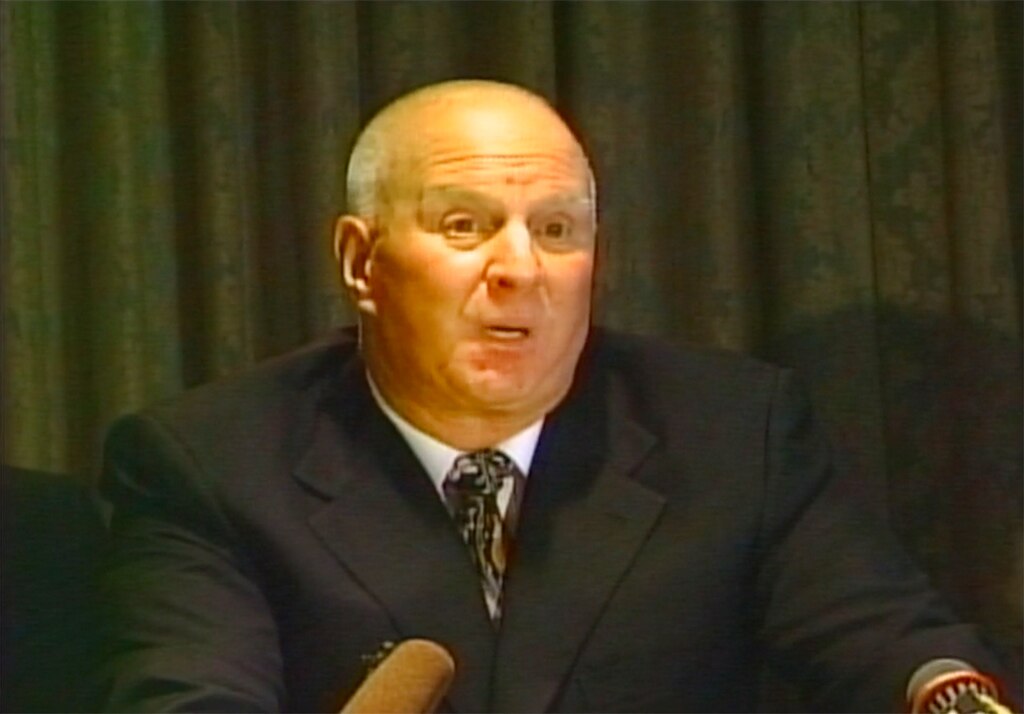

The 77-year-old Snyder implored Boardman at a hearing last month to throw out the case before trial, saying he was innocent and “not well,” referring to his health. The judge declined, as she has previously.

The skilled civil attorney is representing himself, and he has struggled with the very different complexities of criminal court.

Regardless of Snyder’s fate, the trial itself could be vital to drawing attention to the secrecy that allows problems at hospitals to persist, said Anna Palmisano, head of the advocacy group Marylanders for Patient Rights.

She said the group’s members have been “stonewalled” by hospitals when seeking answers about suspected medical errors. And no one knows how regulators respond to specific potential errors.

“The bottom line,” she said she suspects, is that regulators are failing to provide “active oversight of our health care facilities, resulting in a decline in quality of care for Maryland patients and an increase in medical errors.”

The Banner’s Greg Morton contributed data reporting to this article.

Comments

Welcome to The Banner's subscriber-only commenting community. Please review our community guidelines.