The overgrown, grassy lot on a stretch of Philadelphia Road near Interstate 95 could become home to most any business: a bank, barbershop or beauty salon.

But a hexagon-shaped sign declares the White Marsh property’s future use: “Evans Funeral Chapel and Cremation Services.”

Actually opening a crematorium, though, hasn’t proved so easy. For more than two years, funeral home owner Charlie F. Evans and nearby residents have been locked in a battle over the property.

Some nearby residents worry emissions from the crematory’s incinerators could compromise their health. And in that car-intensive part of Philadelphia Road, they worry additional traffic from funeral services could pose a safety hazard.

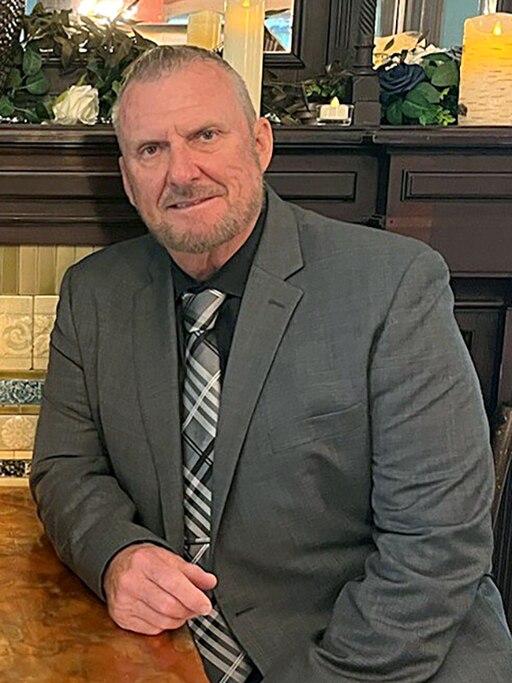

Evans, who owns the lot just south of New Forge Road, contends that the opponents are blowing these issues out of proportion. Funerals and visitation don’t take place during rush hour, for example, he said.

And while incinerators emit particulate matter, cars and fireplaces put out more smoke particles than a crematory, he said, citing data from Matthews Environmental Solution, the company that makes his cremation system.

The yearslong spat underscores the tense relationship between local residents and developers over whether top officials are too friendly to builders. Earlier this year, Baltimore County Council member David Marks downzoned the property to prevent the installation of a crematory, but a county agency already had signed off on the proposed facility.

“This seems to be yet another instance where developers seem to win at every chance,” said Marks, a Republican who represents District 5, which includes the crematory property.

Local residents, like Heather Patti, who leads the White Marsh-Cowenton Improvement Association, have made their case to lawmakers and state environmental officials, mobilized neighbors and spoken at public hearings.

“We intend to use every appeal option,” Patti said. The association has brought the dilemma to the Court of Appeals, where there is still a pending appeal. Patti says they are feeling a financial squeeze from the legal fees.

On Nov. 13, she and others protested the plans at a public meeting held by the Maryland Department of the Environment, which enforces state rules about emissions. It recently extended a 30-day public comment period begun Nov. 21 until Jan. 21.

Evans said he has shelled out more than $2 million for this project and costs grow as the dispute lingers.

“Every time you do something with the county they have a little fee for it,” said Evans, whose business also has locations in Forest Hill, Monkton and Parkton. “It doesn’t take long for it to add up. … The meter still runs.”

Patti suggested Evans should cut his losses and sell the property.

The dispute comes as cremation surges in popularity among families priced out of burials and conflicts over crematories have increased. In 2023, 60.5% of Americans who died were cremated, about twice the rate at the turn of the century, according to the National Funeral Directors Association.

In North Baltimore, residents have been pushing back against a proposed Vaughn Greene crematorium since 2020. Baltimore’s zoning panel and a judge have approved that project, but the city is still pursuing rezoning efforts that could prohibit crematories near residential neighborhoods.

Coming soon?

In White Marsh, the paint on Evans’ “Coming soon!” sign is starting to fade. The grassy lot appears unkempt.

It’s a loss for the community, Evans said. If residents succeed in blocking the project, they could deprive eastern Baltimore County of a useful service, he added.

“Let’s say I live in White Marsh and I want to have my dad cremated. This means my dad has got to go outside of our community,” he said.

“I bet you if I wanted to put a bar up there though,” Evans mused, “it would have been in two years ago.”

A tense meeting

As dozens of residents gathered in the mid-sized church across from Evans’ empty lot on a November evening, some waved signs reading: “No crematorium where we live.”

“Look around. Nobody wants them here,” said Mark Hauf, who sits on the board of the neighborhood association.

Evans said he was surprised the neighborhood couldn’t muster more than 100 people.

State environmental officials tried to ease some of the residents’ concerns.

MDE representative Matt Hafner zipped through a slide presentation highlighting state and federal regulations for crematories. Such rules prevent crematories from emitting visible plumes of gas except water vapor, Hafner said. And the state prohibits the discharge of toxic air pollutants at levels that endanger public health.

Evans said his facility would meet all of these requirements.

But residents made it clear they still believed the crematorium was a health hazard, and that the state was going to let it slide.

“Remember way back when, when we were all told, probably by an air-quality person or somebody from OSHA, that asbestos and lead paint were safe?” Hauf said.

Hauf worries that smoke emissions from the crematory, coupled with exhaust from vehicles on nearby I-95 would increase the area’s vulnerability to cardiovascular disease.

Miriam Garrity, a 76-year-old grandmother, said she was concerned about possible mercury and carbon monoxide emissions that could cause delayed illnesses.

And Andy Dudak Jr. worried that pacemakers and other implants in burning bodies could release toxic pollutants into the air.

Scant research

Pete DeCarlo, a smoke emissions researcher at Johns Hopkins University, said crematory systems generate a negligible level of smoke particles, especially compared to vehicles. Most cremation systems, including the ones that Evans uses, have safeguards that largely block noxious particulate emissions, he said.

“That’s not to say that they don’t have a valid concern,” DeCarlo said.

Prolonged exposure to combustion can cause adverse health impacts, though research that links crematorium emissions to health problems is scant.

“We have to look at things in proportion to what other sources of exposure exist,” DeCarlo said. “If anyone’s burning wood in their backyard and has a little backyard fire pit, those are massive amounts of emissions that come out that which we all kind of just accept and often enjoy.”

As for implants, Jennifer Wright, a supervising crematory operator at another Evan’s crematory location, said pacemakers are always removed because they can be explosive and corrosive if heated. Hip transplants and other similar metal objects aren’t removed, but do not melt during cremation.

The Maryland House of Delegates and state Senate filed joint emergency bills earlier this year that would prohibit “locating a new crematory within 1,000 feet of an assisted living or nursing facility, a property that primarily serves children, or a residential property that is designed primarily for human habitation.”

The proposed crematory in White Marsh would sit across the street from several homes.

“That ought to be enough for everybody to step in and stop this thing because we’re not going to stop it once it’s built,” Hauf said.

Evans has provided tours of one of his crematories, but isn’t sure what more he can do to change residents’ minds.

“They’ve made up their mind,” he said. “They don’t want to listen.”

Comments

Welcome to The Banner's subscriber-only commenting community. Please review our community guidelines.