For more than 60 years, the dense forests of Patuxent River State Park have cradled a secret.

Vines and tall grasses hid the homes of a Black family who triumphed over the horrors of slavery, built a thriving community and launched the AFRO-American newspaper chain.

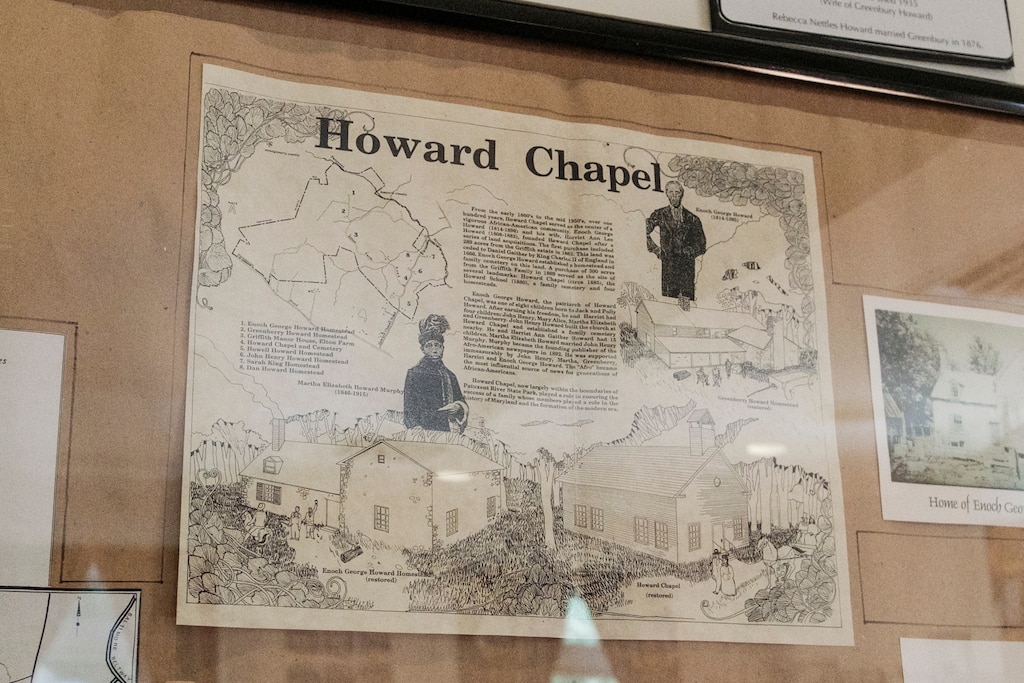

Born enslaved in 1814, patriarch Enoch George Howard was a gifted farmer who could coax bountiful harvests from northern Montgomery County’s tobacco-depleted land. He was also a gifted businessman who convinced his enslaver to allow him to grow and sell his own crops.

Howard saved up to secure his family’s freedom in the early 1850s. Then, as the Civil War raged, he paid $3,000 for Locust Villa, the house in which his wife and children had been enslaved, and its 290 surrounding acres.

The family made their former captors’ estate their home, and, some believe, a stop on the Underground Railroad. They purchased 300 more acres, started a school for Black children, and helped many other Black families establish homesteads nearby.

Enoch George Howard gave the land to establish a church, Howard Chapel, which also became the name of the community.

One of the couple’s daughters, Martha Elizabeth Howard Murphy, helped her husband, John H. Murphy Sr., launch the pioneering AFRO-American newspaper chain, which is still led by their descendants. Their son, Carl J. Murphy, went to Harvard and obtained a doctorate from a German university before taking over the AFRO.

“The Howard family in one generation experienced the full arc of the African-American experience,” said Angela Crenshaw, director of the Maryland Park Service.

Yet when Crenshaw’s predecessors at the park service obtained this parcel of land in the early 1960s, they had little interest in the Howard family story. They saw the land as prime hunting grounds. In time, the earth began to swallow the historic structures.

But in the past decade, a new triumph began to unfold here.

A historian digging around land records rediscovered the Howard properties and built excitement among other state workers. Around the same time, the executive director of Afro Charities came across a well-worn scrapbook that set her on a journey to share the story of the Howards, her ancestors.

And Crenshaw, the state park service’s first Black leader, has made it her mission to correct many wrongs.

Freedman’s State Historical Park was established by the state legislature in 2022 from a 1,000-acre parcel within Patuxent River State Park. Within the next decade, visitors will be able to explore the homes on the old Howard Chapel property, fields and trails where the remarkable family forged its legacy.

But much work remains before the site can be open to the public. And chapters of the family’s singular story continue to be discovered.

Thriving community of free Black people

Between 1830 and 1860, Maryland slave owners sold more than 20,000 people to Southern cotton plantations, ripping families apart, destroying marriages and tearing children from their parents’ arms.

The passage of the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850 made Black life even more bleak. Those who sought freedom could be recaptured even in states that forbade slavery, and free Black people were often seized and sold without a chance to defend themselves.

The lives of free Black Marylanders were bound by harsh conditions. They could be re-enslaved for minimal and spurious infractions, such as “vagrancy” or failing to pay a debt.

Yet somehow against these challenges, Enoch George Howard built a small empire. He purchased his freedom in 1851, then bought the freedom of his wife, Harriet Lee Howard, two years later from a member of the Gaither family, the namesakes of Gaithersburg. She purchased their older children: John Henry, Mary Alice, Martha Elizabeth and Greenbury W. A fifth child, Maria, was born free in 1854.

State records show Howard grew rye and oats, kept cattle, horses and pigs and plowed his land with two pairs of oxen. He also had significant investments and frequently loaned money to other Black families.

When Howard died in 1895, a grandson wrote in his obituary in the AFRO-American that he lent “a helping hand to any of his race who deserved help.”

“Many of those now owning property in Montgomery and Howard Counties owe their present holdings to Mr. Howard’s help,” the grandson, George B. Murphy Sr., wrote.

The Howards made their home the hub of a thriving community of free Black people who provided for and protected each other, much like the residents of Zora Neale Hurston’s Eatonville, Florida.

Montgomery County had a significant population of Quakers who were opposed to slavery and helped those seeking freedom. Still, it was a dangerous place to be Black, both before and after the Emancipation Proclamation. In 1845, white men fired on a group of 70 enslaved people seeking freedom, wounding several; they condemned the leader to death. Three Black men were lynched in the county between 1880 and 1900.

The community that grew up around the Howard family kept each other safe, engaging in what activists now call “mutual aid” or “collective care.”

“This was a community of freed men and freed women,” Crenshaw said “They farmed. They stayed together.”

‘What long, happy days we had’

Sister Constance Murphy, an Anglican nun and a great-grandchild of Enoch George and Harriet Lee Howard, wrote in her memoirs about childhood visits to Howard Chapel in the early 1900s.

Each summer, her parents would drape cloth over the parlor furniture in their Baltimore home and head down to the farm of Constance’s great uncle and great aunt, Greenbury W. Howard Sr. and Rebecca Howard.

Constance and her siblings roamed the family’s hundreds of acres, admiring “horses, cows and pigs and turkeys and chickens, all sorts of grain and fruits, and even a choice plot of tobacco,” she wrote.

So many attended the community’s small church, Sister Constance wrote, that families worshipped at home every other week to reduce crowding.

On Sundays at home, Sister Constance’s father would play Bible readings and hymns on the phonograph, then lead prayers. Afterward, the children tossed horseshoes with their father or explored.

“What long, happy days we had on that farm,” wrote Sister Constance, who died in 2013 at the age of 109.

Other Black Baltimoreans joined the Murphys in escaping the heat and harsh discrimination of the city to visit the Howard Chapel community.

The society pages of the Afro-American chronicle generations of trips to Enoch George Howard’s estate, Locust Villa.

“Mrs. Archie Johnson, and son, and Miss Carrie Dublin, passed through the city this week en route to New York having spent the summer at Locust Villa, Montgomery County,” read a tidbit from a 1906 edition of the Baltimore Afro-American.

History lost and rediscovered

In the middle of the last century, the land passed from Howard descendants to two other families before arriving in the care of the park service.

As rangers focused on hunting and fishing, tree roots muscled under the foundations of the Howard homes. Vines stretched up stone walls. Vandals carted away the cornerstone from Locust Villa.

Hunters littered shotgun shells around Greenbury Howard’s fine stone home. The living room where Sister Constance listened to gospel hymns on the phonograph became scrawled with graffiti, snakes weaving through the ceiling beams.

About a decade ago, Peter Morrill, then a historian with the Department of Natural Resources, was perusing a state property database when he came across entries about the Howard family homes and cemeteries.

After reading the family’s fascinating history, he hiked into the Patuxent River State Park to see what remained.

He was delighted to find that despite decades of neglect, Greenbury Howard’s house still stood strong. Traces of whitewash clung to the stone walls; Aegean blue paint stained the trim. Inside, an ornate, though corroded, tin, ceiling remained. Bits of pottery lie on the kitchen shelves. Beams of American chestnut, more than 150 years old, remained sturdy.

Morrill brought other historians and state workers to Howard Chapel, building excitement about the properties. Then two rangers who felt a duty to preserve and protect the history, Shea Niemann and Erik Ledbetter, became Patuxent’s manager and assistant manager. They soon looped in Crenshaw, who had been instrumental in opening the Harriet Tubman State Park on the Eastern Shore in 2017.

The rangers were struck by the inspiring history that past leaders had ignored.

“It took many, many decades for the park system to be able to talk about difficult histories,” said Morrill, now a historic planner for the park service.

In 2020, Niemann organized a group to cut down the tall grasses, vines and trees that had encroached on the Howard family homes.

Crenshaw and others began sketching out a plan to create a park that would tell the story of the Howard family and the free Black community they nurtured.

Creating Freedman’s park

Plans for the park were formalized in 2022 with passage of landmark legislation to update and improve Maryland’s state parks, The Great Maryland Outdoors Act. The legislation established Freedman’s State Historical Park to “educate the public about and preserve and interpret the lives and experiences of Black Americans, both before and after the abolition of slavery.”

The same year, the park service underwent a major shake-up following The Banner’s publication of an investigation into long-running complaints of harassment, bullying and intimidation at Gunpowder Falls, Maryland’s largest state park.

Crenshaw, one of the department’s most prominent and highly-regarded rangers, was named director of the park service in 2023, becoming the first Black person to lead the organization.

Crenshaw, who wants to increase access to the more that 90 properties managed by the park service, is passionate about the Howard family story and the insight it provides into the lives of Black Marylanders.

“I’m exceedingly moved by this place,” she said. “I want Black people to be comfortable in nature. I want people to come here to see our history, to know that African American history is American history.”

The sites that will make up Freedman’s Historical State Park are under development and not yet open to the public. Early work has been funded by grants and park budget appropriations.

Historic building preservationists have stabilized Greenbury Howard’s house, removed an asbestos-filled addition and are repointing the stone masonry.

The structure requires extensive additional work. The ruins of Locust Villa must be stabilized. The sites of the church and school must be marked. The wooden home of Greenbury’s brother, John, also must be preserved and maintained. Educational signage, maps and publications must be created.

Meanwhile, a team of historians is preparing a detailed report on the land and the families who lived there. And there is much to learn from the many Howard descendants who remain in the area.

‘Hard to get and dear paid for’

Savannah Wood had been back in Baltimore for a few months in 2019 when she came across a faded, brittle scrapbook.

That the scrapbook was more than a century old was not surprising. Wood had recently become the executive director of Afro Charities, charged with preserving, protecting and expanding access to millions of documents, photos and clippings that The Afro’s journalists had compiled over more than 130 years.

For Wood, exploring The Afro’s archive also meant journeying into her own family’s past. Her great-great-grandfather was John H. Murphy Sr., a Civil War veteran who merged the AFRO-American with two other papers, building them into a media empire that began chronicling Black life just after Reconstruction.

Inside the scrapbook were condolence letters marking the death of Martha Elizabeth Howard Murphy, Wood’s great-great-grandmother.

Spellbound, Wood read about her ancestors. Born enslaved, Martha Murphy had inherited land from her father, Enoch George Howard, sold it to her brother, and had loaned her husband the $200 he needed to purchase the Afro-American.

Intrigued by this ancestral land, Wood reached out to the park service and received an enthusiastic response from Ledbetter, Patuxent’s assistant manager. He filled her in on the park service’s research and asked her for help connecting with other relatives.

Wood drove to Patuxent River State Park, left her car at the nature center and hiked through the woods to get to her family’s former property.

“It was fascinating just to imagine that this had been so close to me, growing up in Baltimore all this time, and I didn’t know about it,” she said.

A multimedia artist, Wood was inspired to create a documentary named after one of the parcels of Howard family land, “Hard to Get and Dear Paid For.”

While the full documentary is in development, Wood has created a short film that explores the project’s themes.

“To the land, the past is present,” Wood narrates as the fields and forests and cemeteries surrounding the old Howard homes scroll past.

“The trees have kept watch. My DNA splits around their roots, feeding wild rose brambles from long-disintegrated remains. Did they recognize me when I came back?”

Deep roots in local Black history

Another Howard descendant, Sandi Williams is the executive director of the Sandy Spring Slave Museum and African Art Gallery, a few miles from the new state park.

A great-great-granddaughter of Enoch George Howard, Williams lives in the same area where her family has resided for more than 200 years.

She has an encyclopedic knowledge of the area’s history and greeted by name nearly everyone who passed by the museum on a recent Saturday.

“As the Black community here is changing, it’s important to know the history,” said Williams, who also is also an assistant principal of Wheaton High School. “A lot of newcomers think we just moved here.”

Williams is among hundreds Howard descendants who gather for reunions every other year. Photos in the museum show celebrations held near Howard Chapel and in Canada, where two family members fled to freedom.

Sandra Smith, 81, of Toronto, is a descendant of one of those freedom seekers. Her great-grandfather, Thomas John Holland, was a son of Leatha Howard Holland, Enoch George’s sister. At 16, with his mother’s encouragement, he walked the 360 miles to the Canadian border, then swam across the Niagara River.

A retired principal, Smith visited Locust Villa during family reunions, and felt a connection to her ancestors.

“You touch things and know they touched the same thing ... or walked on the same path,“ she said. ”There’s a feeling of groundedness, of belonging."

Crenshaw envisions The Sandy Spring Slave Museum and African Art Gallery as a stop on a driving tour of sites related to the new park that’s in the works. Other stops include the Sandy Spring Museum, the Underground Railroad Experience Trail and the Sandy Spring Odd Fellows Lodge, a historic Black fraternal organization.

The Freedman’s project, and the park service, suffered a great loss over the summer when Ledbetter, who had devoted years to unearthing Howard family history, died suddenly.

Plans are further complicated by the current assault on accurate depictions of Black history. The Trump administration ordered some national parks to remove exhibits related to slavery, The Washington Post reported this week.

But Crenshaw said Maryland is committed to developing its newest state park.

“The federal government is going to do what it’s going to do,” she said, but the park service has received support from Gov. Wes Moore’s administration “to accurately tell stories about African American history in the state of Maryland.”

Peace. Peace. Rest.

When she leads small tours — of Howard descendants, potential funders, Black outdoors advocates — Crenshaw likes to point out how Greenbury Howard built his home on a bluff. In his later years, he would have been able to look out his window and see the small graveyard where his parents were buried and where he would one day rest.

When Crenshaw and others first walked out here, tall grasses hid the graves of the Howard family. Since then, workers have trimmed back the vegetation, cleaned and straightened the headstones and replaced a fence.

Experts used ground penetrating radar to determine the placement of the remains, Crenshaw said. “Everyone is where they’re supposed to be,” she said.

Crenshaw takes visitors through a cornfield as they approach the cemetery, inviting them to look up and listen to the wind rustling the corn.

Visitors often have a strong reaction to the cemetery, Crenshaw says. Some break down in tears.

When Crenshaw first visited the cemetery, she noticed pieces of blue and white sea glass sitting near the headstones. Upon further research, she learned some African Americans lay sea glass on their ancestors’ graves to wish their spirits a gentle return to Africa.

In the center of the cemetery stands a stately marble obelisk marking the resting place of Greenbury W. Howard Sr. Farther back lie the graves of the couple who started it all, Harriet Lee Howard and Enoch George Howard.

On her headstone is Psalm 23, “Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil: for thou art with me.”

His says simply, “Peace. Peace. Rest.”

Comments

Welcome to The Banner's subscriber-only commenting community. Please review our community guidelines.