People in Baltimore have been dying of overdoses at a rate never before seen in a major American city.

In the past six years, nearly 6,000 lives have been lost. The death rate from 2018 to 2022 was nearly double that of any other large city, and higher than nearly all of Appalachia during the prescription pill crisis, the Midwest during the height of rural meth labs or New York during the crack epidemic.

About the series

The reporters examined the city’s response to rising overdose deaths as part of The New York Times Local Investigations Fellowship. This is the first part in a series exploring Baltimore’s overdose crisis.

A decade ago, 700 fewer people here were being killed by drugs each year. And when fatalities began to rise from the synthetic opioid fentanyl, so potent that even minuscule doses are deadly, Baltimore’s initial response was hailed as a national model. The city set ambitious goals, distributed Narcan widely, experimented with ways to steer people into treatment and ratcheted up campaigns to alert the public.

But then city leaders became preoccupied with other crises, including gun violence and the pandemic. Many of those efforts to fight overdoses stalled, an examination by The New York Times and The Baltimore Banner has found.

Read More

Health officials began publicly sharing less data. City Council members rarely addressed or inquired about the growing number of overdoses. That the city’s status became so much worse than any other of its size was not known to the mayor, the deputy mayor — who had been the health commissioner during some of those years — or multiple council members until they were recently shown data compiled by Times/Banner reporters. In effect, they were flying blind.

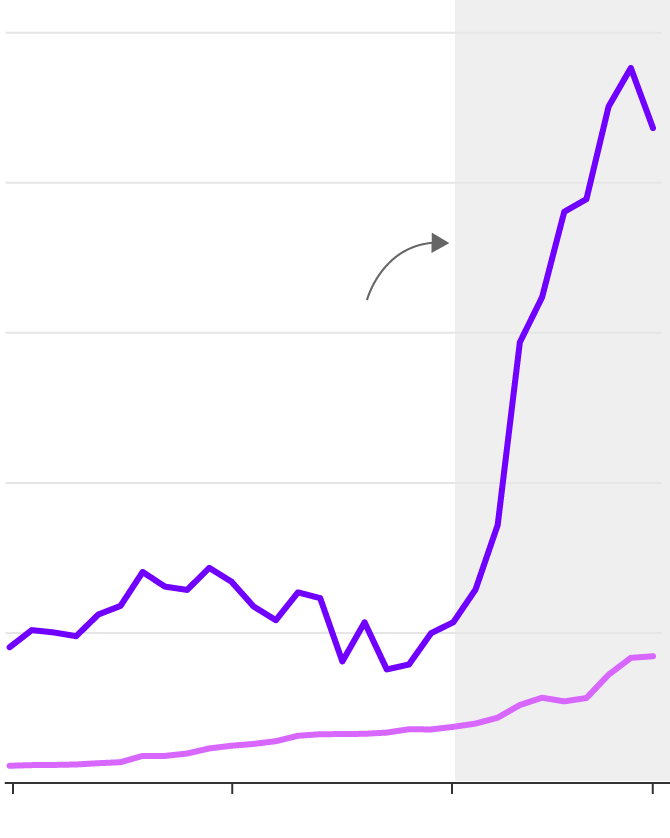

A rapid increase in overdose deaths

Baltimore’s fatal overdose rate has quadrupled since 2013. It dipped in 2022, but preliminary data for 2023, not shown below, indicates overdoses were on track to rise again.

200 deaths per 100,000 people

Baltimore

160

Overdose deaths have

surged because of fentanyl

and other synthetic opioids.

120

80

40

National

1993

2003

2013

2022

200 deaths per 100,000 people

Baltimore

160

Overdose deaths have

surged because of fentanyl

and other synthetic opioids.

120

80

National

40

1993

1998

2003

2008

2013

2018

2022

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention • Molly Cook Escobar/The New York Times

Little of the urgency that once characterized the city’s response is evident today. Since 2020, officials have set fewer and less-ambitious goals for their overdose prevention efforts. The task force managing the crisis once met monthly but convened only twice in 2022 and three times in 2023. By then, fewer people were being revived by emergency workers, fewer people were getting medication to curb their opioid addiction through Medicaid and fewer people were in publicly funded treatment programs.

In an interview, Mayor Brandon Scott defended the city’s response. He knows that Baltimore has had a severe problem with drug addiction for decades, he said, and while the analysis may provide a better understanding of its scale, it will not change his administration’s approach.

“This is an issue that we’re doing a lot of work on and that we can and will do more work on,” Scott said, “but we also know requires a lot, lot more resources” than the city has.

When shown the mortality figures, other city leaders and health experts reacted with alarm.

It’s “really shocking,” said Dr. Joshua Sharfstein, a former Baltimore health commissioner and now a vice dean at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, adding that the deaths were “unprecedented in the city’s history.”

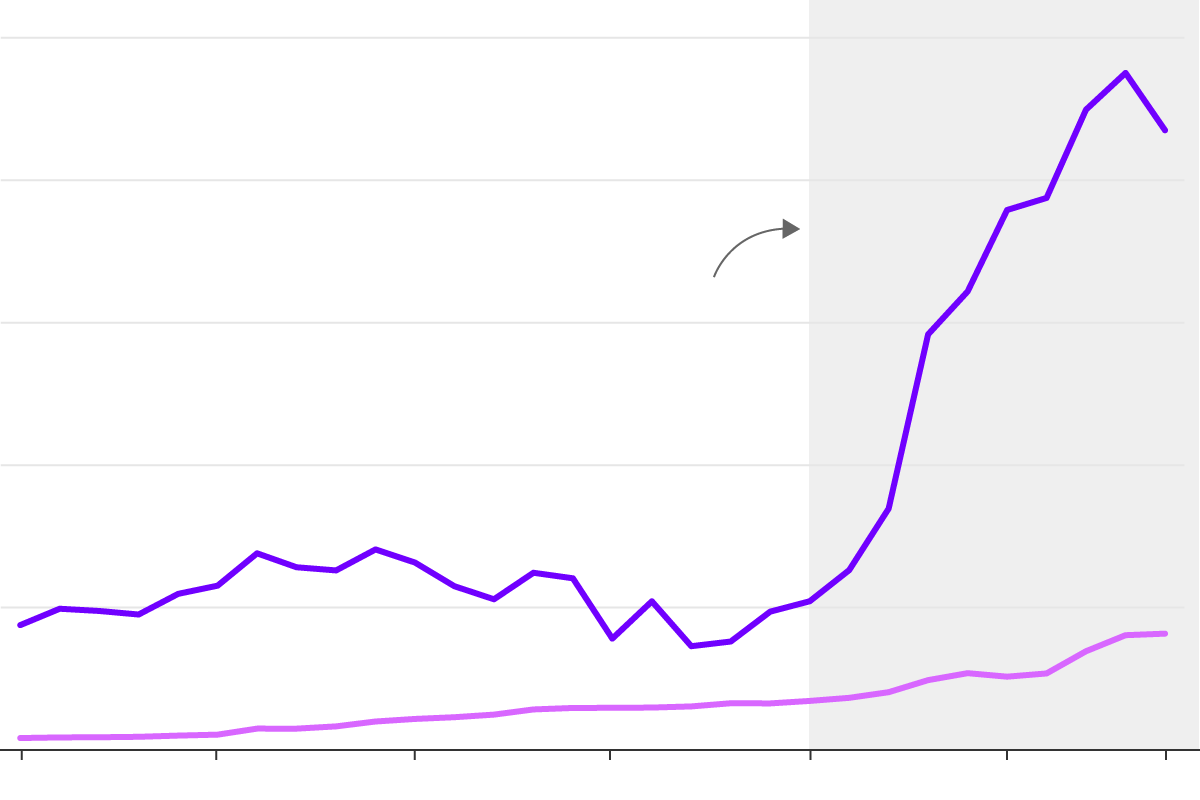

An extraordinary outlier

From 2018 to 2022, Baltimore’s fatal overdose rate far exceeded that of any other large American city. In listings for counties, the major city is shown in parentheses.

COUNTY (CITY)

DEATHS PER 100,000

Baltimore

170

Knox, Tenn. (Knoxville)

86

Davidson, Tenn. (Nashville)

81

Philadelphia

78

Jefferson, Ky. (Louisville)

69

64

Marion, Ind. (Indianapolis)

Camden, N.J. (Camden)

64

San Francisco

64

Montgomery, Ohio (Dayton)

64

59

Franklin, Ohio (Columbus)

COUNTY (CITY)

DEATHS PER 100,000

Baltimore

170

Knox, Tenn. (Knoxville)

86

Davidson, Tenn. (Nashville)

81

Philadelphia

78

Jefferson, Ky. (Louisville)

69

Marion, Ind. (Indianapolis)

64

Camden, N.J. (Camden)

64

San Francisco

64

Montgomery, Ohio (Dayton)

64

Franklin, Ohio (Columbus)

59

Figures represent deaths caused by drug poisoning for counties of 400,000 or more.

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention • Molly Cook Escobar/The New York Times

Councilman Mark Conway, who leads the city’s public safety committee, described the deaths as “completely unacceptable” and said he would have called for hearings if he had known how much Baltimore was an outlier.

The numbers are “horrifying,” said Dr. Laura Herrera Scott, Maryland’s health secretary since 2023, adding, “We haven’t deployed the right resources in the right places.”

To examine Baltimore’s response to overdoses, journalists for The Times and The Banner reviewed thousands of pages of government documents and interviewed more than 100 health officials, treatment providers and people who have been addicted to drugs. Taken together, the records and interviews reveal the extent to which the city’s leaders failed to grapple with the enormity of the crisis.

State and city agencies track deaths, reporting the overall count to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. But Maryland and Baltimore officials, often citing medical privacy concerns, have not published more detailed information on overdoses that is readily available elsewhere. That secrecy has hindered awareness of the epidemic and responses to it, former city employees and community workers said.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

The state’s Office of the Chief Medical Examiner refused to provide full autopsy reports until The Banner won a lawsuit compelling the agency to disclose the information, which identified who died, where they died and how they died.

Those who were lost represented a cross-section of Baltimore: line cook, lawyer, bus driver, engineer, machinist, teacher, restaurant owner, carpenter, veteran, physician, salesman and admissions coordinator for an addiction recovery center. There were retirees and the jobless.

Some victims were heartbreakingly young: Since 2020, at least 13 children under 4 have died after being exposed to drugs, according to the reports. Black men in their 50s to 70s died at the highest rates.

A few overdose deaths drew headlines, but most were invisible to the public.

William Miller Sr., 65 — who founded Bmore Power, an organization that hires people who have used and dealt drugs to give out the overdose antidote Narcan — was discovered in his bathroom in 2020, one day before the birth of his grandson. A single empty gel capsule, commonly used to package powdered drugs, was in the trash can.

He had been shot and survived HIV, hepatitis C and decades of overdoses before becoming a community activist. Concealing his relapses so that others wouldn’t be discouraged cost him his life, said William Miller Jr., his son.

Jaylon Ferguson, a 26-year-old linebacker for the Baltimore Ravens, fatally overdosed on cocaine and fentanyl, according to his autopsy, in an acquaintance’s home in 2022. It was a day before he planned to fly to Louisiana to belatedly celebrate Father’s Day with his fiancée and three children. On the first anniversary of his death, they brought stuffed animals to his grave.

Bruce Setherley, 43, told his mother, Mona, that he was on his way to an addiction program in 2022. She assumed the providers had taken his phone because she didn’t hear from him. Weeks later, he was found dead in an abandoned rowhouse. Mona Setherley now wears a silver bracelet engraved with the word “love” in her son’s handwriting. “I keep waiting for him to come home,” she said.

City Council members described losing friends and seeing people slumped over on the streets. The mayor recalled coming home late one night to find his neighbor passed out on the steps of her apartment. He called 911.

“That happens every day,” he said, “but knowing that, we have to figure out ways to do more.”

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

The sharp increase in deaths came as the city has faced numerous challenges: a shrinking population, tensions over policing following the death of Freddie Gray, turnover at City Hall, as well as rising shootings among young people and Covid-19.

“We have done a great job of trying to focus on multiple epidemics at the same time,” said Scott, a Democrat who took office in late 2020 and is expected to have an easy path to re-election this year.

Many residents say they don’t see the government doing enough. The city needs to be more proactive in aiding people with addiction, said the Rev. Derrick DeWitt, whose church hosts recovery support group meetings in the West Baltimore neighborhood of Sandtown-Winchester.

“These are not the people who say, ‘I need help,’ and go on a bus to go get it,” he said. “You got to bring it to them. You got to hold their hand. The addiction has done so many things. Overdose is the final step.”

A dangerous high

For nearly all of the past three decades, Baltimore has had one of the highest fatal overdose rates of any large U.S. city. But for most of that period, even as the HBO series “The Wire” helped cement the city’s reputation as the U.S. heroin capital, the death rate was much closer to the national average than it is today.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

Officials have long tried to solve the city’s drug problem with arrests and aggressive policing. Baltimore was also at the forefront of innovative public health strategies to address addiction. In 1994, the city’s Health Department was among the first in the nation to start a legal syringe exchange to stop the spread of HIV and other blood-borne illnesses.

Beginning in 2006, the city and state spent millions to expand access to buprenorphine, one of the most effective opioid addiction treatments. Fatal overdoses dropped, and Baltimore seemed to be getting a handle on its heroin problem.

Around the same time, pharmaceutical companies were inundating pharmacies across the country with addictive pain pills. Four hundred thousand pills of opioids like oxycodone started arriving in the city every week. Some patients from both inside and outside the city began selling their pills in Baltimore, expanding the illegal drug market and making it easier for people to get hooked on opioids or to relapse, said Sharfstein, who was city health commissioner from 2005 to 2009.

In a written statement last week, the mayor’s office said that the current fentanyl crisis had been triggered by the influx of pills from drug makers and distributors, and that The Times and The Banner’s reporting on the city’s response amounted to “misguided victim blaming.”

The claim about the drug makers echoes a lawsuit the city is pursuing against more than a dozen companies, set for trial in September. But the prescription pill epidemic was far less severe in Baltimore than elsewhere in the country. Baltimore received a fifth as many pills per capita as some areas, Drug Enforcement Administration records show. Oxycodone was the cause of relatively few deaths in the city, according to CDC and state data.

The death rate remained relatively low until the mid-2010s, when fentanyl flooded illegal drug markets across the country.

Frequent drug users describe being high on fentanyl as a carefree, sometimes euphoric stupor, followed by a painful withdrawal — nausea, anxiety, sweat and flulike symptoms — that drives them to use again.

Dealers began spiking heroin with fentanyl, which is up to 50 times more potent and can be manufactured from cheap chemical compounds. They also began mixing fentanyl in cocaine, pressing it into fake prescription pills and selling it on its own. Drug-testing data shows that it is now all but impossible to buy illegal opioids in Maryland that have not been mixed with it and other dangerous additives like xylazine, which makes naloxone — the generic name for Narcan — less effective. These days, heroin is rarely found.

Because fentanyl is combined with other substances, the distribution of the opioid’s granules is uneven. One hit may be just enough to get high. The next could be deadly.

In 2010, the overdose death rate was near a 20-year low: 29 deaths in the city for every 100,000 residents. By 2015 the rate had doubled, then doubled again three years later. By 2021, it was 190 per 100,000, and three people were dying on average every day.

‘A broken world’

Yvonne Holden, 67, gazed up at the two-story rowhouse where she had grown up in Northwest Baltimore, just down the street from Pimlico Race Course, home to the Preakness Stakes. The porch roof is sagging, the front door boarded up. Abandoned by her family after a fire decades ago, the structure is no longer safe to live in, but her brother, who declined to be interviewed, still calls it home.

He is in his 50s and has long battled addiction. Standing there, Holden considered the impact of drugs on those closest to her. Two siblings contracted HIV from needles and died within a week of each other in 1999. Her best friend passed away from heart problems after long-term cocaine use. Another friend overdosed last year, probably on fentanyl, and cannot speak clearly or use the left side of his body; she now helps care for him.

Holden herself used heroin, and then a mix of methadone and whatever prescription pills she could get, for decades while raising four sons and working as a nurse technician at hospitals across the city. In 2010, with intensive treatment and support from her church, she was able to stop getting high.

In her one-bedroom apartment, where quotes from Scripture hang on nearly every wall, she leafs through her collection of Bibles each day. “It shows you how to live in a broken world,” she said.

On her windowsill, Al Holden, her son, smiles in a baby portrait, all chubby cheeks and tiny fists.

He loved watching boxing videos and dreamed of starting a landscaping business with his brothers. Instead he cycled in and out of prison. On Sept. 21, 2021, a few weeks after he was released for the last time, he was planning to celebrate his 50th birthday with a cookout for family and friends. Yvonne Holden stopped by the house where he was staying that morning, but he said he wanted to rest before the party. As she left, she told him she loved him. “I love you,” he said back.

When she returned less than an hour later, he was kneeling at the side of his bed, head bowed as if in prayer, dead of a fentanyl overdose. His family performed CPR. Holden, who often gives out Narcan on the street with other church members, had none with her that day.

While waiting for the medical examiner’s office to retrieve his body, Holden’s relatives gathered in the backyard with a cake and sang happy birthday to him one last time.

Years of tumult

Alarmed by rising overdose deaths in 2014, Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake created a task force to plan a response.

The city’s health commissioner, Dr. Leana Wen, widely distributed Narcan before it was available without a prescription, and the Health Department trained police officers and the public in how to use it. The department also opened a “crisis stabilization center,” a place to find help after an overdose. It created an alert system to send aid groups to overdose clusters and piloted a “real time capacity tracker” to help patients and doctors find open treatment slots.

The city issued detailed plans and prioritized public awareness. One effort, promoted on billboards and bus stops, was a website called DontDie.org, designed to “knock people over the head” about the risk of fatal overdoses.

Wen described the initiatives to Congress and spoke on a panel with President Barack Obama. In 2018, a national group of health officials honored the department.

Even then, coordinating a response across city agencies was difficult, said Amanda Latimore, a Health Department epidemiologist at the time.

The city’s Law Department was resistant to agencies sharing overdose data, she recalled in an interview, sometimes citing the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, or HIPAA, the federal law that protects patients’ medical information. Assembling the data she needed to understand trends in overdoses and treatment took “almost an act of God,” she said, and happened only because Wen and her team had a near-singular focus on the topic.

As overdose deaths continued to accelerate, the next mayor, Catherine Pugh, drew criticism when she objected to the proliferation of treatment centers within neighborhoods, saying that people needing help for addiction would have a better chance if they were removed from Baltimore’s drug-afflicted communities and “put on a plane to Timbuktu or somewhere.”

Wen left the agency in October 2018. Pugh resigned the next year in a corruption scandal, the second mayor criminally charged in a decade.

By the time Scott was elected, in November 2020, an interim mayor had been in place for a year and the Covid pandemic was in full force. Scott, previously City Council president, had for years pushed for supervised drug consumption sites as a way to prevent overdose deaths. They have never been approved in Maryland.

Baltimore also had one of the country’s highest homicide rates, and Scott’s administration prioritized reducing shootings. (When homicides fell by 20% last year amid a national decrease, Scott credited his administration’s efforts.)

While there were three times as many drug deaths as homicides, some of the overdose initiatives began to fade away during those tumultuous years.

The capacity tracker was hardly used: Only six out of 160 addiction service providers ever posted their wait times. The city now says the effort has been abandoned.

So has the “Don’t Die” public awareness campaign. The website stopped working sometime around February 2023, according to the Internet Archive. At some point, the Health Department stopped updating the overdose pages on its website altogether, and did not resume for years.

(Tell us about your experience with addiction treatment programs in Maryland.)

The multiple crises, and resulting turnover from mayor to mayor, had “lasting ramifications” for city agencies, said Conway, the councilman.

“I wonder if changes in leadership and lack of focus or guidance has resulted in a lot of these things falling apart,” he said. “And you end up with the situation where you don’t know what you don’t know, and you don’t know that these programs even existed or that they stopped existing.”

Scattered efforts

Baltimore’s overdose response involves a number of city agencies and community groups, many of which receive government funding. Emergency workers rush to scenes of suspected overdoses and revive thousands of people every year, with a special crew giving Narcan and pamphlets to people they find nearby. Johns Hopkins doctors run a mobile medical clinic out of a van in collaboration with the city. The Health Department recruits local celebrities to raise awareness at schools.

The state and federal governments spend hundreds of millions of dollars each year combating drug addiction in Baltimore. Medicaid’s annual spending on treatment programs grew significantly in recent years, reaching $245 million last June.

A publicly funded nonprofit whose board is led by the city health commissioner, Behavioral Health System Baltimore, or BHSB, also gave out more than $50 million a year in grants for drug and mental health treatment, with most of that money coming from state and federal funds. The organization said it did not track its addiction and mental health spending separately, because services overlapped. But a Times/Banner analysis shows that its spending earmarked for drug treatment dropped by about $5.5 million from 2019 to 2023, though some of the decline was explained by Medicaid’s beginning to cover certain services.

The job of coordinating all these efforts belongs to the city Health Department. The department runs the state-mandated Overdose Prevention Team, which is tasked with sharing data, identifying problems and developing a citywide strategy. The group cut back to meeting just a few times a year. In 2020, it released a three-year plan that it described as “intentionally brief,” given the pandemic. One goal: Become “more action-oriented.” Another: List the ways people could get Narcan. Since then, it has not published updates or a new plan.

In a statement, the Health Department said the committee had working groups that met more frequently but declined to say how often, or which goals it had achieved, citing the lawsuit involving the pharmaceutical industry.

The 900-person department itself had only three full-time positions in 2022 to work on drug addiction and mental health which doubled to six in 2023 with state funding, according to budget documents.

The city pays for just one of those positions. It spends very little of its revenue on the Health Department’s mental health and addiction budget: a yearly average of $1.5 million since 2016. (In a statement, the mayor’s office said this figure did not include the cost of overdose prevention programs run by other agencies or other parts of the Health Department. The staffing figures would also not include employees working on those programs.)

The department last presented data on overdose deaths to the City Council in 2020. The numbers it showed then were from 2017 and 2018, when the fatality rate was a quarter less than it is now. Even after a local television station, WBAL, reported last year that a San Francisco Chronicle database showed Baltimore was a large outlier, many of the officials Times/Banner reporters interviewed said they were unaware.

Dr. Letitia Dzirasa, a deputy mayor who had been health commissioner from 2019 to 2023, said in an interview that she knew the rate in Baltimore was the highest in Maryland, and higher than in other large cities in the region, but did not know its ranking nationally among all counties. Her successor, Dr. Ihuoma Emenuga, declined repeated interview requests.

On occasion, there were signs in public that the response was disjointed. In 2021 and 2023, Councilwoman Danielle McCray, head of the health committee, called meetings for city agencies to talk about fighting overdoses. She asked how the Police and Fire Departments were sharing information about overdose hot spots. Representatives of those agencies had no satisfactory answers, McCray said in an interview.

She asked whether the city could create a dashboard tracking the number of overdoses. A Health Department representative said that the department was working on it but that the state’s restrictive data-sharing rules made it hard. The city would ultimately launch one last year — eight years after it first said it should build one.

“We just need to all work together on this issue with a greater sense of urgency,” McCray said in the interview.

All the while, some treatment efforts were reaching fewer people than before.

The number of patients in the city’s public treatment system, which helps poor and uninsured people with addiction, dropped by almost 5,500, or 16%, in 2023 from 2020, even as the amount of money being spent on it soared, according to state data. The number of Medicaid patients on drugs that treat opioid addiction, long a staple of Baltimore’s response, also fell by thousands.

State officials said that the pandemic, and a policy change in 2020 that allowed Medicare to cover payments for medication, might have contributed to the drops.

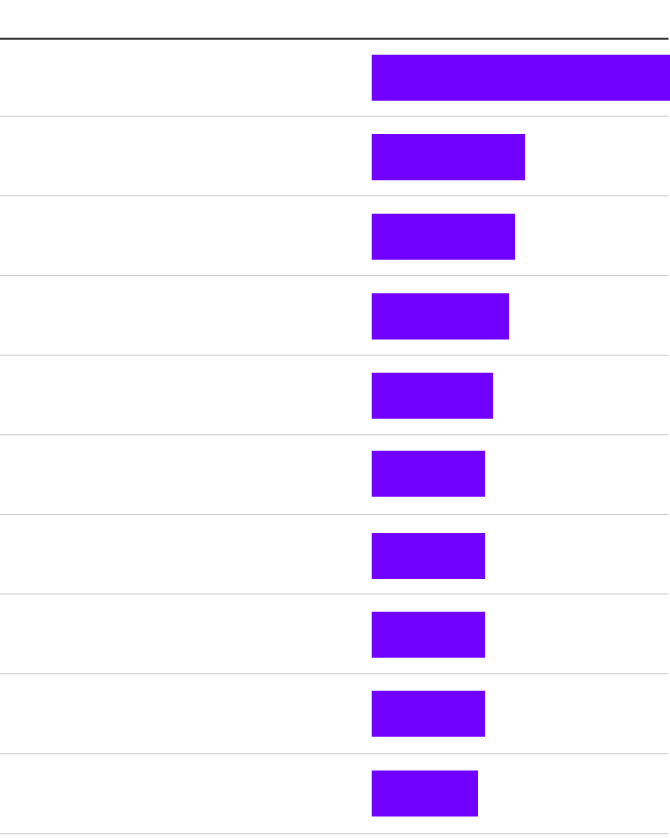

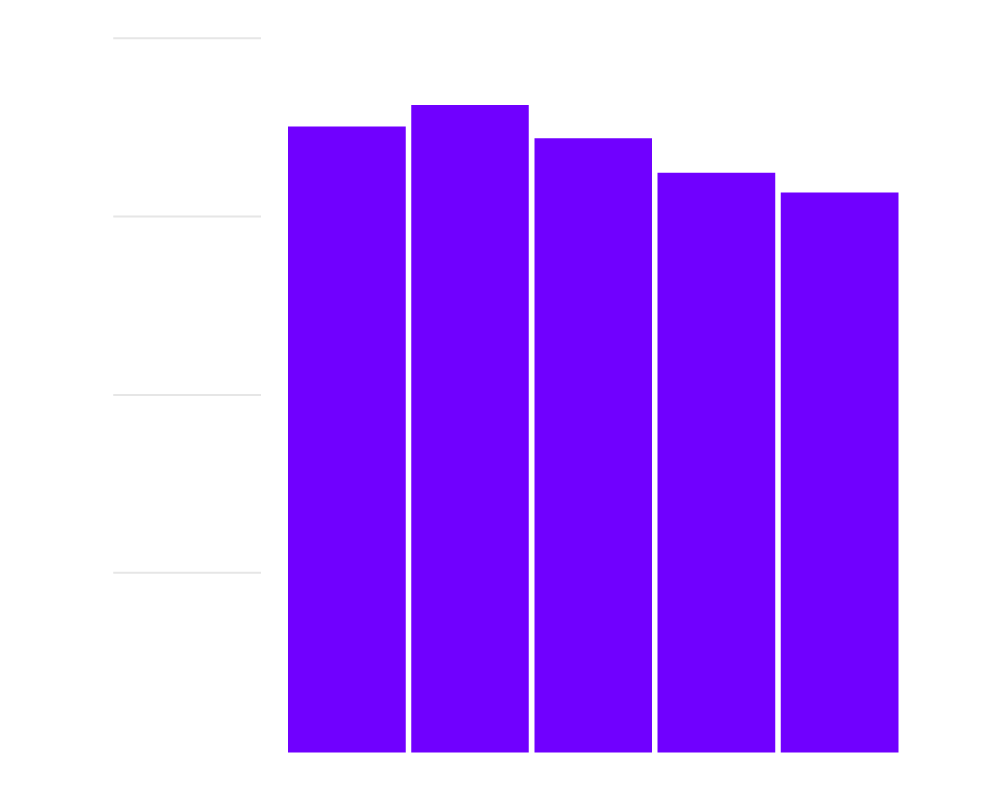

Fewer people getting medication support

Medications that help patients control their cravings for opioids are effective. But the number of Medicaid patients getting them in Baltimore have dropped, even as the number of people fatally overdosing has shot up.

20,000 people

18,158

15,681

15,000

10,000

5,000

2018

2019

2020

2021

2022

20,000 people

18,158

15,681

15,000

10,000

5,000

2018

2019

2020

2021

2022

Source: Maryland Department of Health • Molly Cook Escobar/The New York Times

City officials did not always seem to know what to make of their own statistics.

The number of people being revived from overdoses annually by emergency workers dropped by nearly 1,000 in 2023 from 2018, while deaths rose significantly. It is not clear why that happened, said James Matz, assistant chief of emergency medical services for the Fire Department. “I don’t know the answer for that, I’ll be honest with you,” he said in an interview.

Dr. Herrera Scott, the health secretary, said Maryland’s overdose response needs to be based on a sophisticated understanding of the data. She acknowledged that the department had had challenges with data sharing previously, but said the state was now using data to better target its efforts and planned to start publishing information about deaths in specific neighborhoods.

In his annual State of the City address in March, Scott said he was creating an overdose prevention cabinet. His administration, which announced the plan after reporters began asking city officials about overdoses, provided few details, except that the cabinet would include top city leaders.

A national outlier

Other parts of the country with lower death rates have addressed overdoses more aggressively.

In Portland, Oregon, the city, the surrounding county and the state declared a 90-day state of emergency this year; agency leaders met daily to coordinate services and share data. In San Francisco, a 2021 mayor’s emergency declaration led to outreach efforts in a particularly hard-hit area and what has been described as a supervised drug consumption site, which the city closed the following year after pushback. Both places have hundreds of fewer deaths each year, even though they are significantly larger than Baltimore, which has a population of roughly 570,000.

Some states and counties have seized on strategies that experts say can make a difference.

Vermont, for example, created a “hub and spokes” model that connects addiction centers to a network of prescribers, such as family doctors, who work together to get people the help they need. It now serves about 12,000 patients a year.

Baltimore started its own “hub and spokes” pilot in 2017. But in 2023, one of the city’s two treatment hubs served only 88 patients. The other organization is no longer using that model.

Some cities send teams of trained professionals, such as recovery specialists, EMTs and sometimes law enforcement officers, to knock on people’s doors 24 to 72 hours after they overdose to offer connections to treatment and other help. Those initiatives in Houston; Louisville, Kentucky; and Montgomery County, Ohio, each reach hundreds of people a year.

Studies show the effort can work; one tracked people the Houston team contacted over three months and found that more than half stayed in treatment and none overdosed again. In Baltimore, the city’s emergency rooms offer connections to care and resources. But the only team that reaches out to those who refuse to go to a hospital after an overdose was given the names of just 50 people by emergency workers last year, according to Gabby Knighton, executive director of People Encouraging People, which runs the group.

People struggling with addiction in Baltimore are often left to find help on their own.

Vernon Hudson Jr., 54, first took opioids as a defensive end on Virginia Tech’s football team, when he was given a painkiller after a knee injury. He returned to Baltimore from college with a growing addiction and no football career. He cycled from relapse to recovery for more than two decades.

In December 2021, he sniffed a powdered drug and then overdosed while driving, crashing his Mustang into the front steps of a church. He regained consciousness in the back of an ambulance after being administered naloxone. Racked with shame, he refused to go to a hospital.

With the help of a support group, he has since stopped using drugs. But in the ambulance, at the time of his overdose, no one offered to connect him to any treatment resources or social services, he said. After he asked to get out of the vehicle, he said that no one from the city checked up on him again.

Cheryl Phillips and Eric Sagara contributed reporting. Susan C. Beachy and Kirsten Noyes contributed research. This article was reported in partnership with Big Local News at Stanford University.

Resources

People experiencing mental health or substance use crises can call or text 988 or visit 988LifeLine.org at any time to connect with a trained counselor.

Naloxone, or Narcan, is a life-saving overdose reversal drug. Learn how to use and where to get naloxone for free from the Maryland Department of Health.

About the analysis

The Times and The Banner analyzed anonymized data about every death in the United States between 1989 and 2022 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The data, obtained under an academic license through the reporter Nick Thieme’s affiliation with Columbia University, shows demographics and causes of death. Fatalities from 1968 through 1989 were collected from a separate data set the C.D.C. publishes.

Fatality rates in this article measure deaths that occurred in Baltimore, not deaths of Baltimore residents, and are calculated across the country by dividing the total number of overdose deaths that occurred in each jurisdiction by its population. For that reason, totals will differ from those in the C.D.C.’s online database, C.D.C. Wonder, which measures deaths by place of residence and also excludes deaths of people who live in U.S. territories or outside the United States.

The C.D.C. reports data by county, and the analysis identified large U.S. cities by looking at counties of at least 400,000 people. Baltimore City is reported as its own county. Overdose fatalities are those in which the underlying cause of death is listed as drug poisoning.

The Banner also sued the Maryland Office of the Chief Medical Examiner to obtain autopsy data, which allowed reporters to explore detailed geographic patterns of overdose within the city.

Death rates are not calculated for U.S. territories or Washington, though rates for both are significantly lower than in Baltimore.

Comments

Welcome to The Banner's subscriber-only commenting community. Please review our community guidelines.