Baltimore has become the center of the worst drug crisis ever seen in a major American city, an examination by The New York Times and The Baltimore Banner has found. The city’s death rate from 2018 to 2022 was nearly double that of any other large city — a fact not known by several top leaders, including the mayor and the deputy mayor, who used to lead the city’s Health Department.

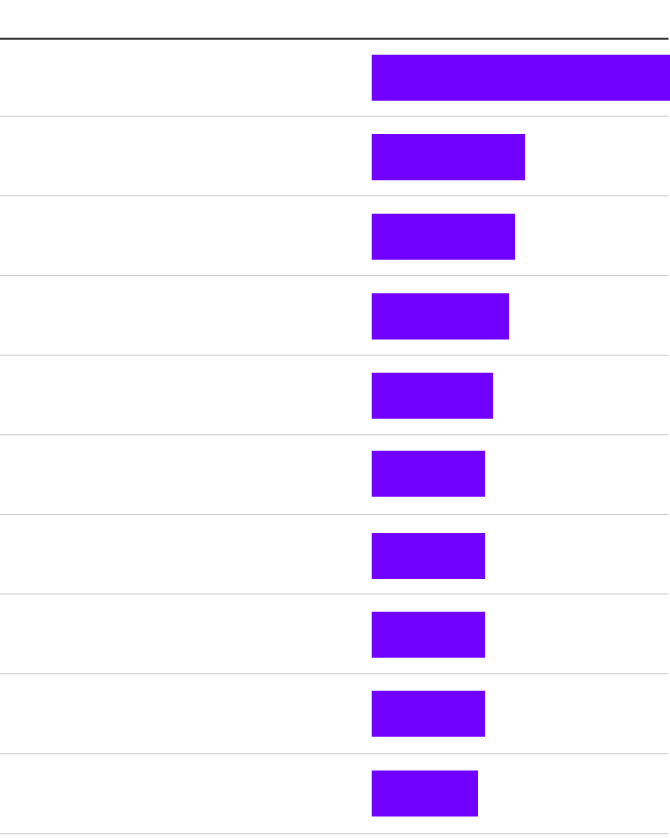

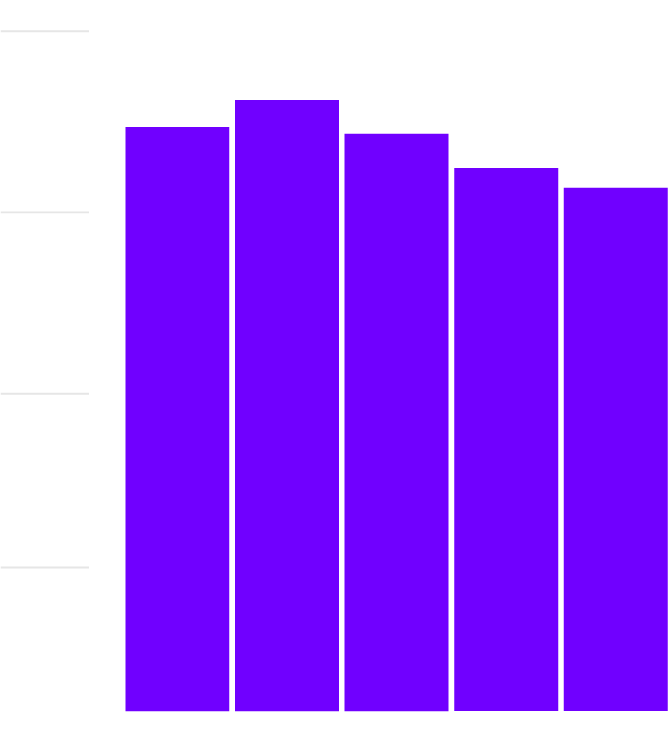

An extraordinary outlier

From 2018 to 2022, Baltimore’s fatal overdose rate far exceeded that of any other large American city. In listings for counties, the major city is shown in parentheses.

COUNTY (CITY)

DEATHS PER 100,000

Baltimore

170

Knox, Tenn. (Knoxville)

86

Davidson, Tenn. (Nashville)

81

Philadelphia

78

Jefferson, Ky. (Louisville)

69

64

Marion, Ind. (Indianapolis)

Camden, N.J. (Camden)

64

San Francisco

64

Montgomery, Ohio (Dayton)

64

59

Franklin, Ohio (Columbus)

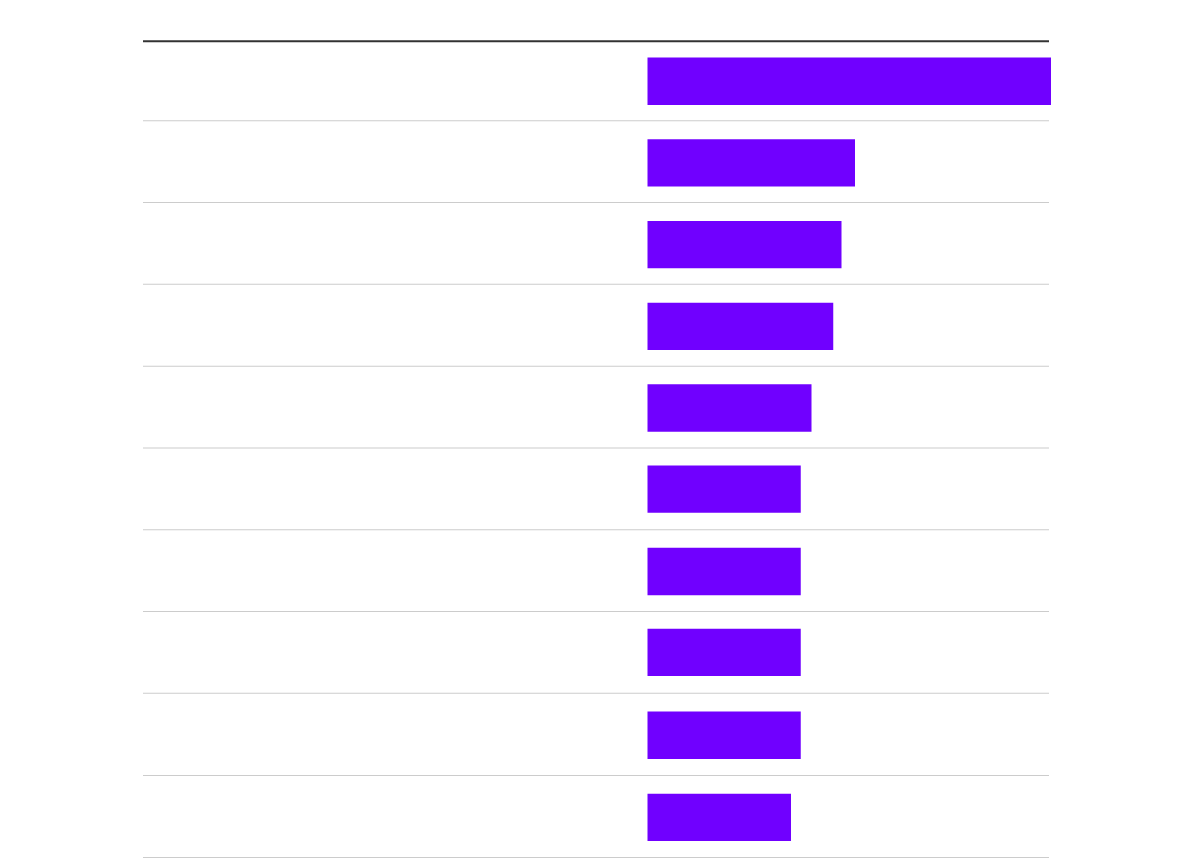

COUNTY (CITY)

DEATHS PER 100,000

Baltimore

170

Knox, Tenn. (Knoxville)

86

Davidson, Tenn. (Nashville)

81

Philadelphia

78

Jefferson, Ky. (Louisville)

69

Marion, Ind. (Indianapolis)

64

Camden, N.J. (Camden)

64

San Francisco

64

Montgomery, Ohio (Dayton)

64

Franklin, Ohio (Columbus)

59

Figures represent deaths caused by drug poisoning for counties of 400,000 or more.

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention • Molly Cook Escobar/The New York Times

The city once had an aggressive overdose prevention strategy, but as officials became preoccupied with other crises, many of their efforts stalled.

Read More

Reporters for The Banner teamed with The Times’ Local Investigations Fellowship, which gives local journalists a year to pursue an investigative story about their communities. They reviewed thousands of pages of government documents and interviewed more than 100 health officials, treatment providers and people who have been addicted to drugs to examine the city’s response.

Here are five takeaways from our reporting.

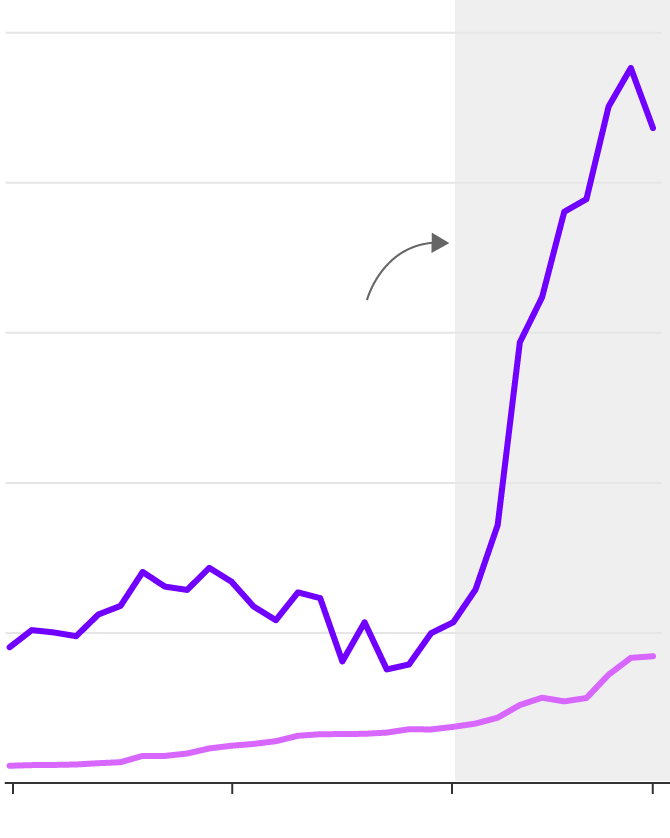

Baltimore’s fatal overdose rate has always been high, but fentanyl drove it to unheard-of levels.

Baltimore has long been known as the United States’ heroin capital — a reputation cemented by the HBO series “The Wire” — and for decades it has had one of the highest fatal overdose rates of any large U.S. city. But the synthetic opioid fentanyl, up to 50 times more potent than heroin, has taken over the city’s drug supply, and the death rate has shot up. These days, nearly all illegal opioids available in the city contain fentanyl, and heroin is almost impossible to find.

Three people die on average every day. Here’s what happened to the city’s fatal overdose rate:

A rapid increase in overdose deaths

Baltimore’s fatal overdose rate has quadrupled since 2013. It dipped in 2022, but preliminary data for 2023, not shown below, indicates overdoses were on track to rise again.

200 deaths per 100,000 people

Baltimore

160

Overdose deaths have

surged because of fentanyl

and other synthetic opioids.

120

80

40

National

1993

2003

2013

2022

200 deaths per 100,000 people

Baltimore

160

Overdose deaths have

surged because of fentanyl

and other synthetic opioids.

120

80

National

40

1993

1998

2003

2008

2013

2018

2022

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention • Molly Cook Escobar/The New York Times

We sued for records to understand Baltimore’s unfolding epidemic.

Maryland’s Office of the Chief Medical Examiner refused to provide autopsy reports that identified who died, where they died and how they died.

The Baltimore Banner sued to get them, and a judge ruled in our favor. The reports provide a vivid picture of how the losses from overdose have spread across the city. They showed that fatal overdoses had occurred on every third city block, that bodies had been found in view of some of the city’s most iconic institutions, and that at least 13 children under 4 had died since 2020 after being exposed to drugs.

Baltimore was at the forefront of innovation in public health. But city leaders focused on other problems, and their response became disjointed.

The city had a long history of innovative public-health strategies, and when deaths from fentanyl began to increase, health officials responded with urgency. They set ambitious goals, distributed Narcan widely, experimented with ways to steer people into treatment and ratcheted up campaigns to alert the public. The efforts won an award from a national group of health officials in 2018.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

But the city faced challenges, from the indictment of a prior mayor in 2019 to tensions over policing following the death of Freddie Gray. Most recently, it has had to contend with rising shootings among young people and COVID-19.

Health officials began publicly sharing less data. City Council members rarely addressed or inquired about the growing number of overdoses. Since 2020, officials have set fewer and less ambitious goals for their overdose prevention efforts. The task force managing the crisis once met monthly but convened only twice in 2022 and three times in 2023. By then, fewer people were being revived by emergency workers, fewer people were getting medication to curb their addiction through Medicaid and fewer people were in publicly funded treatment programs.

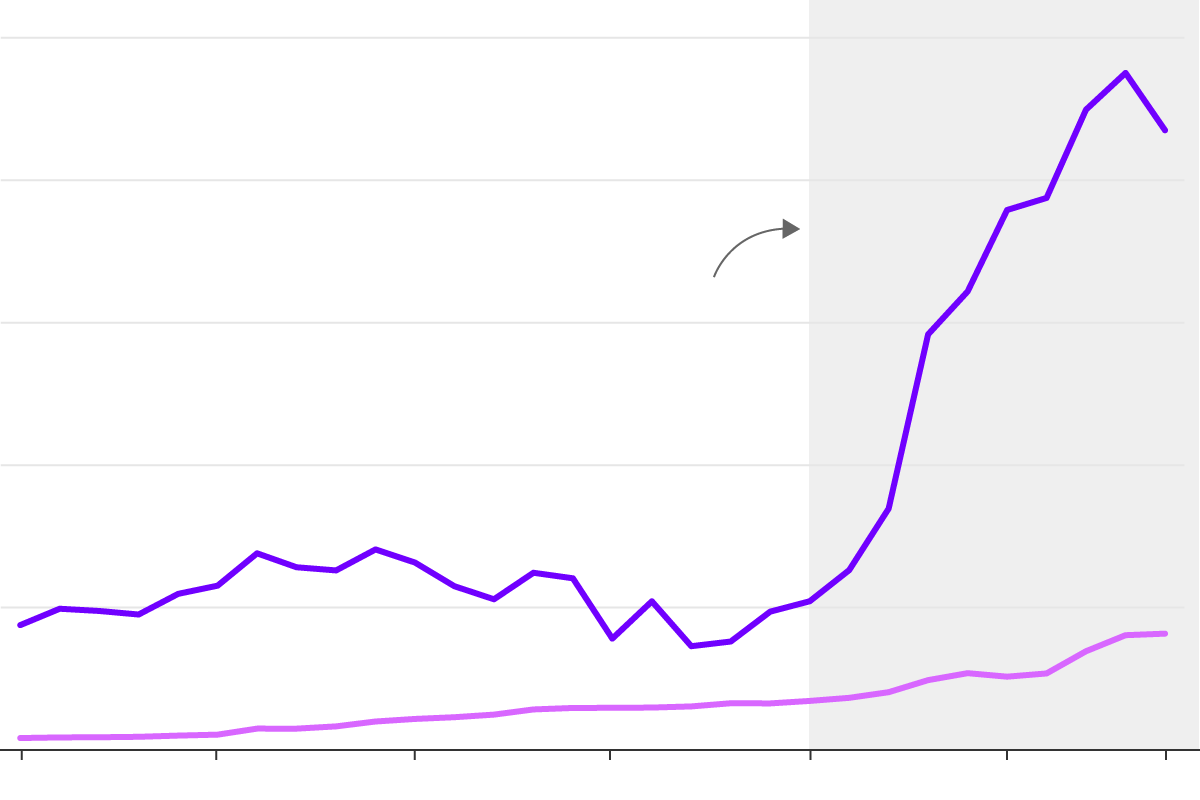

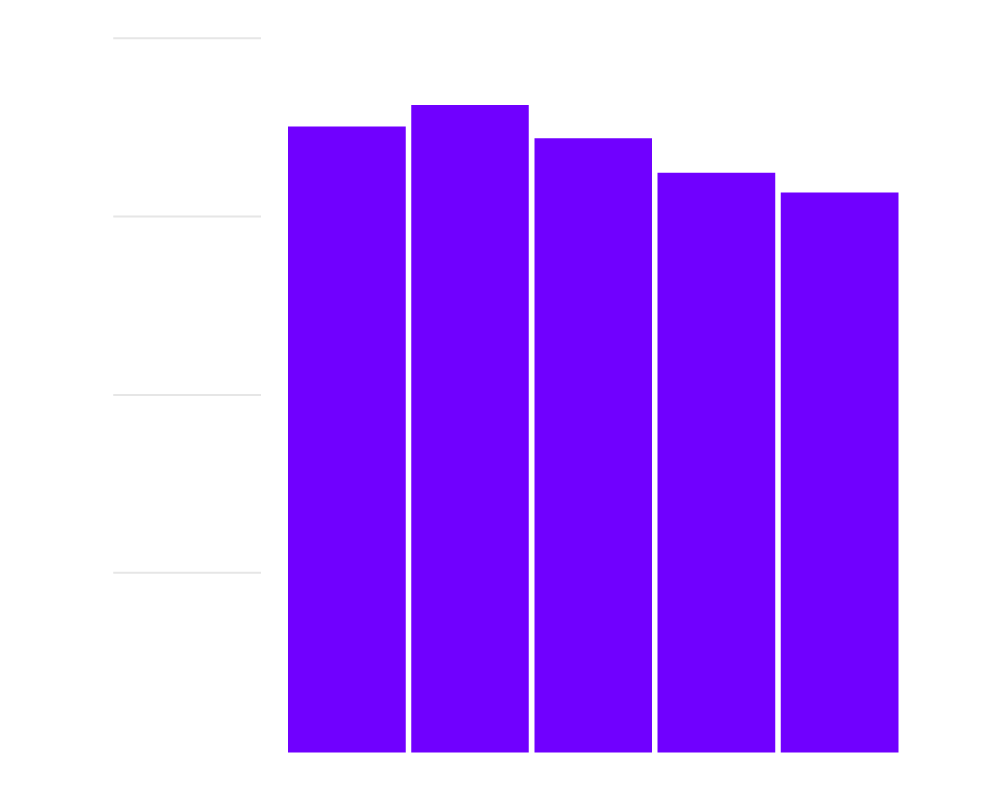

Fewer people getting medication support

Medications that help patients control their cravings for opioids are effective. But the number of Medicaid patients getting them in Baltimore have dropped, even as the number of people fatally overdosing has shot up.

20,000 people

18,158

15,681

15,000

10,000

5,000

2018

2019

2020

2021

2022

20,000 people

18,158

15,681

15,000

10,000

5,000

2018

2019

2020

2021

2022

Source: Maryland Department of Health • Molly Cook Escobar/The New York Times

City leaders and health officials had a wide range of reactions to what we found.

- Mayor Brandon Scott defended the city’s response. “We have done a great job of trying to focus on multiple epidemics at the same time,” he said, adding that the city would do more but needed additional resources. His office blamed pharmaceutical companies, which the city is suing.

- Councilman Mark Conway, who leads the city’s public safety committee, described the deaths as “completely unacceptable” and said he would have called for hearings if he had known how much Baltimore was an outlier.

- It’s “really shocking,” said Dr. Joshua Sharfstein, a former Baltimore health commissioner and now a vice dean at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, adding that the deaths were “unprecedented in the city’s history.”

Nearly 6,000 people have died in six years.

William Miller Sr., 65 — who founded Bmore Power, an organization that hires people who have used and dealt drugs to give out the overdose antidote Narcan — was discovered in his bathroom in 2020, one day before the birth of his grandson. A single empty gel capsule, commonly used to package powdered drugs, was in the trash can.

Jaylon Ferguson, a 26-year-old linebacker for the Baltimore Ravens, fatally overdosed on cocaine and fentanyl, according to his autopsy, in an acquaintance’s home in 2022. It was a day before he planned to fly to Louisiana to belatedly celebrate Father’s Day with his fiancée and three children. On the first anniversary of his death, they brought stuffed animals to his grave.

Bruce Setherley, 43, told his mother that he was on his way to an addiction program in 2022. She assumed that the providers had taken his phone because she didn’t hear from him. Weeks later, he was found dead in an abandoned rowhouse.

About the series

The reporters examined the city’s response to rising overdose deaths as part of The New York Times Local Investigations Fellowship.

Comments

Welcome to The Banner's subscriber-only commenting community. Please review our community guidelines.