One windy Sunday in late February, Ryan Heidenreich pulled through the tall black gates surrounding Greater Grace World Outreach’s East Baltimore complex. Several tumultuous years had passed since he last attended church.

Heidenreich, whose family was once revered at Greater Grace, wasn’t there to worship. He was on another kind of mission, one that filled him with equal measures of dread and purpose.

Four years before, a group of former church members sitting around a campfire had stumbled upon a common truth. Nearly all knew someone who had been sexually abused by high-profile men from Greater Grace.

About this series

This is the third story in a series investigating allegations of child sexual abuse at Greater Grace World Outreach and the church’s handling of the accusations.

• Part I: Megachurch warned of hell, then hid its own sins

• Part II: Web of sex abuse leads to trusted pastor and his sons

• Greater Grace responds: Baltimore pastor defends church’s record on child sex abuse: ‘If we know it, we act on it’

Heidenreich and other ex-members had spent the years since delving into the sins of the church. They made scores of calls, comforted traumatized victims, and explored online archives that put the scope of the crimes and the church’s secrecy into sharp focus. They began calling themselves The Millstones.

With trepidation, they had brought their copious spreadsheets and interview notes to reporters. Now Greater Grace leaders knew that their handling of child sexual abuse allegations was being scrutinized.

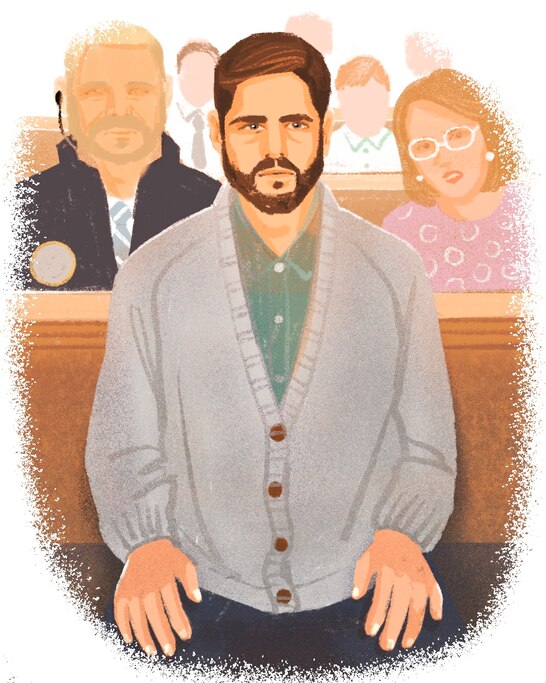

And so Heidenreich, 27, had come to the sprawling campus on Moravia Park Drive for what would likely be the last time. He felt a twinge of nostalgia for the gym where he had played high school basketball.

But he was there to send a message: We’re here. We’re not afraid of you. We won’t be silenced.

‘A lost and dying world’

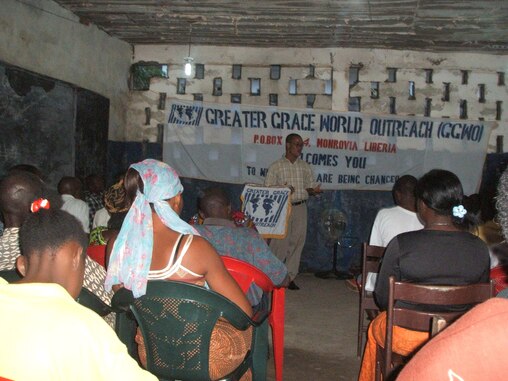

For nearly half a century, missionaries from the church have traveled abroad to win souls for Christ.

“It is the greatest of thrills actually to minister in foreign countries,” reports a book published by the church in the 1970s that describes missionaries working in El Salvador, Finland, England and India.

“We see these disciples, who were some of those first long-haired hippies at the school, leave comfortable America to preach the message of love and life to a lost and dying world,” the book continues.

Thanks to this spirit of evangelism, there are now 550 Greater Grace offshoots outside the United States and more than 1,000 missionaries around the world, the church claims on its website. A map on the site lists 354 churches in 72 countries.

The Heidenreichs moved their family to Ghana in 2002 with great enthusiasm. Chuck Heidenreich, a former member of the U.S. Ski Team, was a newly minted pastor and a graduate of Maryland Bible College and Seminary, Greater Grace’s divinity school. His wife, Sue, was eager to support her husband’s work and raise their four children to serve others.

In sun-soaked Ghana, the Heidenreich kids grew close to another church family — a bond that survived as the years ticked by and the distance stretched across oceans.

Sari Heidenreich grew especially close to Georgetta Gbumblee, the niece of a pastor who worked closely with her father.

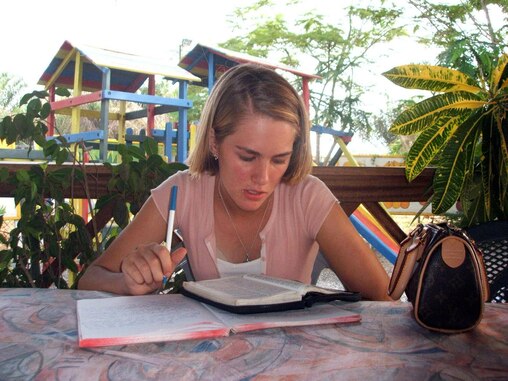

One day in 2017, a decade after Sari Heidenreich left her family’s home in Ghana to attend college in the United States, her phone buzzed while at a work conference in San Diego.

“I want to talk to you about something important, so let me know when you’re free,” Gbumblee texted. “I think I can trust?”

As Sari Heidenreich listened from seven thousand miles away, Gbumblee’s story tumbled out. Her uncle, Pastor Henry Nkrumah, who helped raise her, had sexually assaulted her in their home repeatedly, she said.

Almost immediately after marrying her aunt, Nkrumah singled her out, Gbumblee said, telling her she was his favorite among her siblings, and kissing her on the lips.

Around the time she turned 15, family members said they spotted her uncle slipping into her bedroom at night, Gbumblee said. She noticed worrying signs that something was wrong, but didn’t know what to do. Her bedroom door handle never seemed to lock properly, and she often woke up groggy, fearing she had been drugged.

Reluctant to complain to her aunt, with whom she had a strained relationship, Gbumblee didn’t say anything. Years passed. Then one night, she said she woke up and found her uncle in her room, molesting her. She stopped him, she said, and soon after told her aunt, who called a family meeting. Pastor Nkrumah apologized for his actions and vowed to never touch his niece again, Gbumblee said.

But after six months, the abuse resumed, she said. Gbumblee moved out of the home a few months later.

Now in her 30s and married, Gbumblee said trauma from the abuse persists. She startles easily — her husband’s touch can make her flinch. If she’s in bed and he opens the door, she’ll jump up, heart racing.

Nkrumah did not respond to repeated requests for comment. Greater Grace officials in Baltimore declined to answer specific questions about alleged abuse in Ghana, but said the church abides by state mandatory reporting laws and “cooperates with any investigations conducted by law enforcement or childcare agencies.”

Gbumblee had made Sari Heidenreich promise not to tell anyone. So for two years, she carried Gbumblee’s secret in silence.

Then came another revelation: Someone else was saying she had been abused by a Greater Grace pastor in Ghana. And this person was even closer to Sari Heidenreich. Her sister.

‘I shouldn’t have been touched that way’

For two decades, the woman had been haunted by memories of abuse.

In 2010, when the family left Ghana, the girl told her parents that she had been touched inappropriately by Pastor John Jason, a highly respected Ghanaian pastor who was a spiritual mentor and close friend to her father. The pastor denied it, and her parents dismissed the incident as a misunderstanding.

Now she was in her early 20s, studying for a graduate degree in social work. As she read about caring for trauma survivors, she finally found the words to tell her parents what really happened.

It began when she was 9 or 10, the woman said in an interview. In the back of a Range Rover heading to a church function, Pastor Jason grabbed her hand and guided it to his genitals, then touched her genitals as she tried to wriggle away, she said. This happened several times as the SUV rumbled along.

Other times, he would pull her onto his lap, caressing her genitals through her clothing, she said. When he invited her to the bedroom where he often worked, she always found a way to refuse.

“This man clearly felt he could do anything, anywhere,” the woman, now 28, said in an interview. “I knew I shouldn’t have been touched that way.”

The Heidenreichs were heartbroken by their daughter’s disclosure. She had suffered at the hands of a man they trusted as a colleague, mentor and friend. They did not doubt their daughter for a moment.

But nor did they doubt Greater Grace, the church to which they had devoted their lives. They were confident church officials would do the right thing and take prompt action against Pastor Jason.

They had faith.

Family urged to drop it

Chuck Heidenreich remembered cases in which pastors were stripped of their ordination for extramarital affairs or drinking alcohol in public. Surely Greater Grace leaders would take prompt action against a pastor accused of a crime as heinous as molesting a child.

He went straight to the top, to two friends he had worked with for years: Thomas Schaller, Greater Grace’s powerful and charismatic head pastor, and Steven Scibelli, the boisterous foreign missions director, who oversaw the hundreds of outposts and missionaries around the world.

According to the Heidenreichs, Schaller told them they had three options. They could confront Jason and possibly strain their relationships with friends in Ghana. They could let Scibelli handle it. Or they could just wait for God to mete out justice.

Scibelli urged Heidenreich not to confront Jason, and vowed to question the pastor himself, the parents recalled.

But they could not — would not — let this go. The church might be able to pretend it wasn’t a problem, but the Heidenreichs wanted justice. In July 2019, Chuck Heidenreich boarded the 10-hour flight to Ghana to confront Jason himself and demand his resignation.

This was the process church leaders extolled from the Book of Matthew, to approach someone “who had fallen into sin” face-to-face.

The elderly pastor vehemently denied the allegations and refused to step down, Heidenreich said.

Reached by phone in Ghana and asked if he would like to comment on the allegations against him, Jason said, “Not really.” Greater Grace officials did not respond to questions about the pastor.

Back in Baltimore, Heidenreich appealed to Greater Grace’s board of elders, which Schaller and Scibelli lead. But the 11 high-ranking pastors countered that Greater Grace did not have authority over Jason, according to a letter they sent to their Ghanaian counterparts that Heidenreich reviewed.

Heidenreich wasn’t buying it. He knew church leaders had reprimanded plenty of international Greater Grace pastors. They even used the pastors’ sins as fodder for sermons about the price for straying from God. This was nothing more than a flimsy excuse to keep ignoring sexual abuse.

Plus, the letter Baltimore church leaders sent to Ghana was incomplete, Heidenreich recalled.

It said a serious accusation had been made against Jason, but it didn’t describe the misconduct. A second letter sent at the Heidenreichs’ urging did detail their daughter’s accusations, but the Ghanaian church leaders refused to consider it, Heidenreich said, citing Jason’s years of service. At the time, Jason belonged to the Ghanaian board that could have held him accountable, Heidenreich said.

Ghanaian church officials did not respond to requests for comment.

‘I do not have interest in reading it’

As his parents were repeatedly stymied by church leaders, Ryan Heidenreich, too, wanted to do more to hold Greater Grace accountable. He convinced his sister, Sari Heidenreich, 34, to help. The other two sisters, including the one allegedly abused by Pastor Jason, said they didn’t have the time or emotional energy.

Sari Heidenrich had left Greater Grace, joined a progressive Lutheran church, married and was working for a nonprofit’s human rights campaign. She knew that Ghumblee’s experience demanded a reckoning, and she asked for permission to share her friend’s story.

When she broke the news to her family in fall 2019, her father was stunned. Nkrumah had been his close companion and protege in Ghana. They had founded a church together.

Now Chuck Heidenreich had another trusted friend and spiritual leader to confront. Heidenreich said the call was short, Nkrumah’s voice flat. He said he would think about the allegations and get back in touch. He never did.

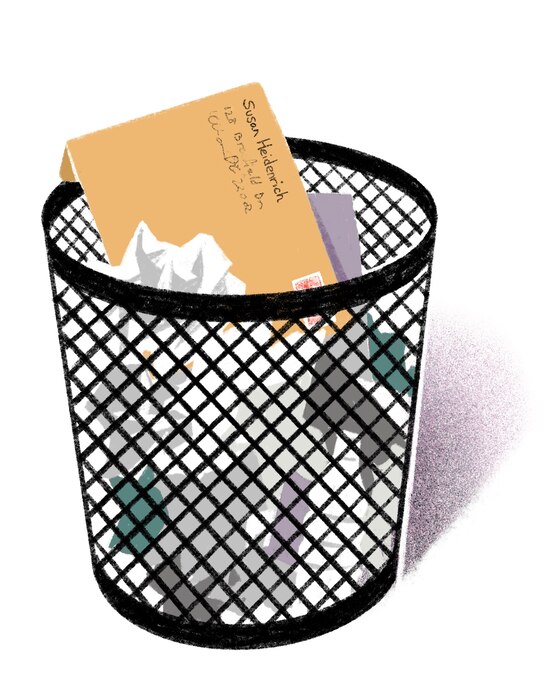

The following day, Sue Heidenreich attempted to deliver a letter detailing Gbumblee’s allegations to Greater Grace’s board of elders. Scibelli threw the envelope back at her, she recalled. Shaken, she picked up the envelope and returned home, she said.

A few hours later, Scibelli sent Chuck Heidenreich an email.

“I do not have interest in reading it or receiving accusations against a man of God,” Scibelli wrote, according to a copy of the email shared with The Banner. “I have no desire to talk or fellowship with you.”

The Heidenreichs were devastated. A man who they had considered a close friend for decades had rebuked them, because they sought justice.

They had dedicated their lives to Greater Grace. But church leaders were failing to take steps to prevent these men from having access to other children. It was one thing to not know about the accusations, but it was unconscionable to refuse to even listen to them.

The Heidenreichs had been fighting for accountability for more than a year and had nothing to show for it. It was time to leave Greater Grace.

‘Protecting the brand over people’

Several months later, a slip of the tongue led the Heidenreichs to another accusation against Pastor Jason.

Scibelli, the pastor who oversaw overseas missions, asked the Heidenreichs if they had been talking with the Mahoneys, another former missionary family. Then he clammed up.

What was there to talk to the Mahoneys about, they wondered. Sari Heidenreich contacted the family’s youngest daughter, Carrie Mahoney, to hear her story.

As a rising star in the international Greater Grace community, Pastor Jason — the man accused of molesting one of the Heidenreich sisters — made frequent visits to the United States.

On these trips, he often stayed at the Massachusetts home of the Mahoney family, former Greater Grace missionaries who had helped establish the church in Ghana. The family did not have a guest room, so when Pastor Jason visited, Carrie often gave up her bedroom and camped out on the couch, she told The Banner.

Jason lavished attention on Carrie Mahoney, making the 6-year-old feel special. But soon he began cornering her alone and molesting her, she said. He groped her as she lay on the couch while her family slept.

Mahoney’s most troubling memory of the abuse stems from a trip to Baltimore in the late 1990s for the church’s annual convention. This year’s event starts next week.

While she was looking at a booth along the perimeter of the convention hall, among hundreds of people, Jason sidled over, unzipped her shorts and slid his hand in her pants, she said.

The girl had been taught to be good, to not make a fuss, to be respectful to elders — especially clergy— and to be chaste until marriage. Filled with conflicting impulses, she froze. “I couldn’t make sense of it,” said Mahoney, now 33.

For years, she kept the secret to herself. But then Mahoney started seeing a therapist and was flooded by memories of the assaults. In 2020, Mahoney told her parents, who were devastated that their daughter had suffered so long in silence.

Carrie’s father, Rich Mahoney, a former Greater Grace missionary, called Pastor Jason, his old friend, the next morning. “He said he didn’t know what I was talking about,” Rich Mahoney recalled.

The Mahoneys then turned to Scibelli, asking him to punish Jason and notify the Ghanaian congregation of the allegations against the pastor.

In a January 2021 email reviewed by The Banner, Scibelli wrote to Rich Mahoney that both he and the local board of elders had asked Jason to resign, but the pastor declined.

In the email, Scibelli also listed sanctions that could be taken against Jason and his church, including revoking financial support, removing the church from Greater Grace’s web page and ceasing visits to the church.

But he said Greater Grace officials in Baltimore did not have authority over Jason’s church. “Affiliation is a friendship,” he wrote. “No legal ties to Greater Grace World Outreach other than friendship.”

Mahoney said Scibelli told him that church officials ultimately asked Jason to retire and become a pastor emeritus. Jason and Nkrumah continue to preach at Greater Grace-affiliated churches in Ghana, and Scibelli continues to visit. A photo of Jason waving the Ghanaian flag even appears prominently on the church’s website.

Greater Grace leaders “are protecting the brand over the people,” Mahoney said. “That’s the opposite of the Christian faith.”

Not afraid, and not going away

That unseasonably warm and windy Sunday in February, Ryan Heidenreich eyed a security car parked near the church entrance, then walked inside.

Nearly four years had passed since The Millstones began their work. They had uncovered more than 50 allegations of abuse, both in this country and abroad. They had interviewed survivors, their parents, siblings, partners and friends. Again and again, they said senior leaders of Greater Grace had failed to take action against the accused pastors.

As a child and teen, Heidenreich had heard repeatedly that people who left Greater Grace fell into ruin, destroyed by the temptations of the secular world. But he had grown convinced that it was the church that damaged lives. He had stopped by Greater Grace a year ago to confront senior pastors, but they refused to listen. He hoped this time would be different.

He was back to say he was not afraid. He and his family were flourishing outside the church. And they would not forget how church leaders had shunned them for speaking out against abuse. He was proud to be part of a group holding church leaders accountable.

Heidenreich wove through the crowd to a seat in the center of the front row, stopping to greet family friends and former teachers. One of the church’s many pastors stepped over to say hello; Heidenreich refused to shake his hand.

Minutes later, an armed security guard approached Heidenreich and asked him to step outside. He declined.

Two other security guards, both wearing bulletproof vests and carrying guns, whispered in each others’ ears nearby. One moved to sit directly across from the pastors who were taking their places on the stage. The other guard, a tall man with a shaved head and neck tattoo, slipped into a seat two rows behind Heidenreich.

Heidenreich ran his fingers through his wavy brown hair, then rested his hands on his lap, fingers fluttering nervously.

The music began, and around him people stood swaying.

From the pulpit, head pastor Thomas Schaller recited a verse from Psalm 119: “I hate vain thoughts, but thy law I love.” He continued to lament the “downward spiral of moral teaching in our society.”

Murmurs arose from the 300 or so people in the church. Many took out notebooks and jotted down Schaller’s words.

“Churches are empty. Pastors are walking in Gay Pride parades,” Schaller said. “Churches are being sold. Churches are being turned into apartments or mosques.”

“It’s an abomination,” a voice called from the audience, as Schaller segued into a discussion of gender nonconforming people.

On stage that day, Schaller told the story of Mordecai from the Book of Esther, who protested King Ahasuerus’ plan to kill all Jewish people in Persia. Mordecai ripped his clothes, put on sackcloth and ashes and cried at the king’s gates to call attention to the plan.

“That’s like us,” said Schaller. “When something is wrong, can you say it?”

Yes, Heidenreich thought. He could.

After a final hymn and prayer, the congregation rose and milled about. Heidenreich greeted family friends, who asked about his parents and sisters; he wondered if this would be the last time they’d speak to him.

He wound through the crowd to the hallway where Schaller was shaking hands with congregants. The security guards were nowhere to be seen, and for a moment, Heidenreich was finally face-to-face with the man who had repeatedly rejected pleas for accountability.

He clapped the pastor on the back as if greeting an old friend.

Then he whispered in his ear: “The Millstones are here.”

Resources for survivors of sexual assault & religious trauma

- MCASA: Maryland Coalition Against Sexual Assault.

- RAINN Get help 24/7. Call the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network by dialing 800.656.HOPE.

- The Trevor Project: A nonprofit focused on preventing LGBTQ suicide. Visit TheTrevorProject.org or text 678-678.

- The Reclamation Collective: A network of therapists who specialize in religious trauma. Visit ReclamationCollective.com for more.

Comments

Welcome to The Banner's subscriber-only commenting community. Please review our community guidelines.