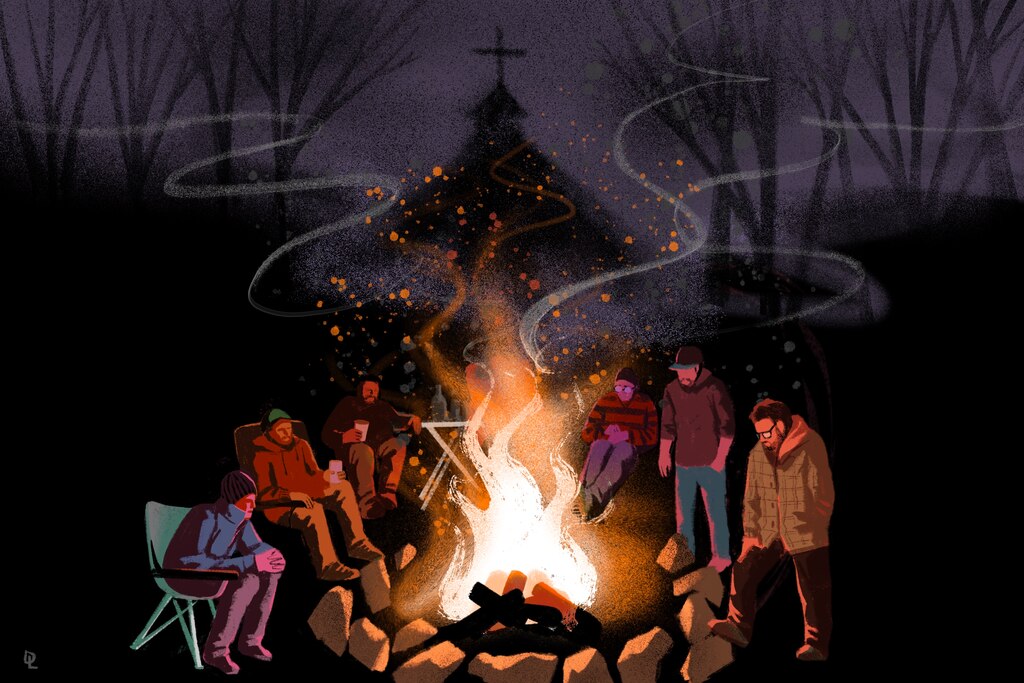

The guys drove up to the edge of the Blue Ridge Mountains that brisk November day, set up their tents, lugged coolers from the car and started a fire. That was one thing they had learned in the church — how to work together, heads down, focusing on the shared task.

That evening, the young men sank into folding chairs around the fire, cracking open beers. The camping trip was an annual tradition, a way to support each other as they carved out lives beyond Greater Grace World Outreach, the East Baltimore-based evangelical megachurch in which they were raised.

About this series

This is the first story in a series investigating allegations of child sexual abuse at Greater Grace World Outreach and the church’s handling of the accusations.

• Part II: Web of megachurch sex abuse leads to a trusted pastor and his sons

• Part III: One family’s agonizing journey to uncover secrets and abuse at a Baltimore church

• Greater Grace responds: Baltimore pastor defends church’s record on child sex abuse: ‘If we know it, we act on it’

This time, the conversation turned dark. I’ve got to get something off my chest, one of the friends said. Years ago, he said, my aunt was babysitting and she walked in on a man molesting his son. He named the man, a prominent pastor in their church.

For a moment, the only sounds were the pops and crackles of the fire. Then another man spoke up: That same pastor ... his son abused my sister.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

Soon they were all talking at once. There was youth leader and coach Ray Fernandez, serving time for molesting three boys years ago — including one man sitting at the campfire. And Jesse Anderson, a camp counselor and Sunday school teacher who received an unusually light sentence for sexually assaulting a boy.

They spoke of loved ones who had been victims of abuse. My sister. My cousin. My friend. Me.

The men had been taught since childhood to ignore the controversies that swirled around the church, whose influence extends to hundreds of affiliate churches around the world. They had been told not to watch the “60 Minutes” segment from 1987 about “intimidation and manipulation” at the church. They knew little of the judge who ordered the church to return $6.6 million to a donor in the 1980s, accusing the founding pastor of “deceit and insincerity.” They ignored critics who described the church as “cult-like.”

The Greater Grace faithful were the lucky ones, their teachers said, God’s chosen people.

Panic rose in Matt Veader’s chest as he listened to the men around the campfire. As a graduate student in social work, he knew he had a legal obligation to report allegations of abuse.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

He was also thinking of his wife, Johanna, all that she had suffered in the church, the years of therapy to process the married 40-something pastor who manipulated her as a teen — a claim the pastor denied. Veader thought of the church leaders who told them to move on, to forgive as Jesus had forgiven.

Veader did not know it then, but this conversation around the campfire would spark an investigation that would consume the next four years of his life and threaten his relationships with loved ones still in the church. He and his friends would talk to 32 former Greater Grace members who said they had been sexually abused as children by men of the church, primarily prominent pastors or leaders. Sources they trusted would tell them of 18 additional abuse survivors.

Again and again, those people said high-ranking pastors dismissed their allegations or pressured them to forgive the perpetrators. Church members who pushed for accountability were condemned from the pulpit and accused of trying to harm the ministry. Seeking justice wasn’t brave, the leaders said — it was vain.

Greater Grace officials declined to address specific claims and issued a statement saying the church “fully cooperates with any investigations conducted by law enforcement or childcare agencies.” Officials said they abide by laws that require adults to report “suspected or actual child abuse.”

“We welcome and support their interventions, expertise, and authority to bring perpetrators to justice for the protection of society,” church officials said.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

But on that day in the fall of 2019, Veader and the others felt compelled to uncover the extent of abuse. How else could they hold church leaders accountable and protect children?

‘To know Pastor Stevens is to know Christ’

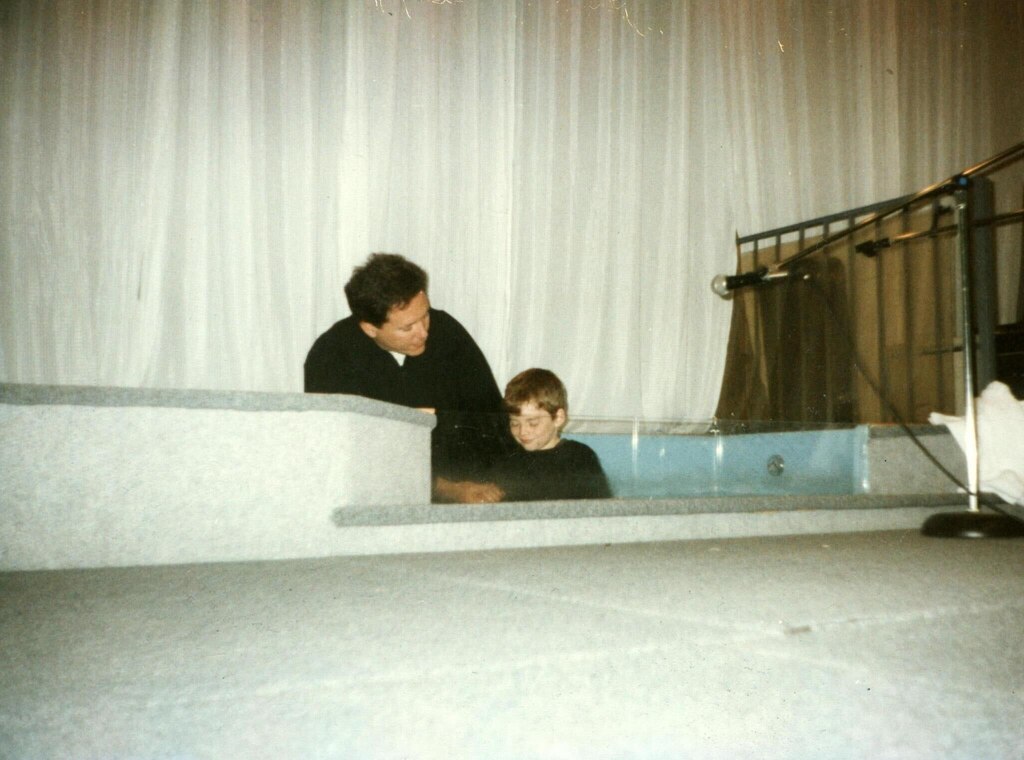

Veader stood on his tiptoes to see the Easter play at Greater Grace. He was in early elementary school.

An “unsaved” man sat onstage watching the Orioles and drinking a forbidden beer. His wife pleaded with him to join her at Greater Grace and be saved.

“I don’t care about Jesus,” said the man. “And I don’t believe in that stuff.”

The man’s words echoed through the auditorium as the stage floor swung open. Smoke and the screeches of scrabbling demons rose from the pit. While Veader watched, horrified, Jesus cast the man into the abyss.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

As an adult, this was something Veader talked about with his therapist. Hell, his debilitating fear of it, and this terrifying scene that had been burned into his memory since childhood.

From his mother’s womb, the church had been woven into Veader’s life. He attended Greater Grace affiliated-schools through high school. His weeks were filled with Bible studies, youth groups and trips to proselytize in the streets of Baltimore. Each June, a convention drew Greater Grace members from around the world to the city. This year’s event starts next week.

As a teen, Veader would hunker down in his room to listen to cassette tapes of sermons by Greater Grace’s founder, Carl Stevens.

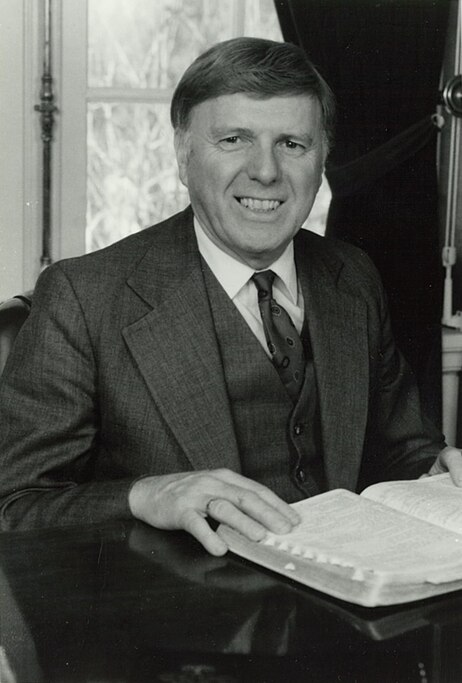

Stevens’ story was remarkable. The former appliance salesman arrived in a tiny Maine town in the early 1960s, burning with religious fervor.

In a dilapidated church, Stevens began a Southern Baptist-style congregation, which he called “The Bible Speaks.” Soon hundreds were flocking to the church. Stevens was not particularly handsome or charismatic, but people were drawn to his fiery sermons and his certainty. He told them what they needed to do to get to Heaven.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

In wide-lapeled suits, he preached at outdoor rallies, in paid TV spots and on a syndicated radio program. He wore a blonde toupee that made him look a bit like Jimmy Carter.

But there was a dark side to Stevens, recalled his son, Paul.

Paul Stevens was 9 when a boarder in their home, a mechanic in his 30s, sexually assaulted him, he said. For months, Paul stayed silent as the abuse continued, until one day, his mother found him in bed with the boarder. He said she screamed and started hitting the man. That night, she told her husband, the pastor. Carl Stevens kicked out the boarder, but did not tell police.

Carl Stevens told his son it was shameful, a secret to hide. “If you ever do anything like that again, I will put you up for adoption,” his son recalled him saying.

“I really remember, even at that age, thinking, it’s all about him. I knew I wasn’t going to see any justice,” Paul Stevens, 67, said in a phone interview. “It was always ministry first.”

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

By the mid-1970s, Stevens’ church had expanded into Lenox, Massachusetts, acquiring a former boarding school for $900,000 — more than $5 million today — and growing the Bible college he started in Maine. Families sold their homes, gave the proceeds to Stevens, and moved into the dorms, committing nearly every moment of their day to the church.

Again and again they heard that to question church teaching is to question God. Those who spoke or even heard criticism of the church could be divinely silenced – perhaps by suffering a heart attack, stroke or family tragedy.

Members felt an intense personal connection to Stevens.

“Everything in my life revolved around that man,” recalled Sirpa Buono, one of a bevy of secretaries required to follow Stevens to public appearances and tote his Bibles. “I dressed the way he wanted me to dress; I did my hair the way he wanted me to do my hair.”

Another former secretary, Rita Taylor, said Stevens asked her not to have children so she could focus on her work, which ranged from translating the New Testament from the original Greek to fetching ice cream in the middle of the night to meet Stevens’ wife’s cravings.

“To know Pastor Stevens is to know Christ,” rhapsodized a 1970s church publication, “The Bible Speaks: Book of Miracles.”

“What was it like to walk with Jesus, to see His smile, to be looked upon with that piercing glance, and to hear His precious voice speak those sanctified Words?” the book states. “Those in The Bible Speaks stopped wondering years ago.”

‘He used my faith in God against me’

Matt Veader had always been driven to help people; for a man in the church, the best way to do that was to become a pastor.

As others his age were savoring the freedom of college, Veader was getting up before dawn to work as a chimney sweep, then heading in the evening to Maryland Bible College and Seminary, Greater Grace’s unaccredited institute of higher education. Weekends were consumed by church activities.

In the midst of this, Veader met Johanna Grimm, a quiet young woman whose deep brown eyes burned with a faith as intense as his own. He was volunteering in the church print shop, scanning old pamphlets and sermons, and she would drop by with a burrito, knowing he was often too engrossed in his work to eat.

They weren’t allowed to date. Grimm’s pastor at Greater Grace forbade unmarried men and women from spending time alone; kissing and holding hands were also taboo. So they hung out with their families or other young people from church. Eventually, in August of 2012, they got engaged.

Soon after, Grimm and Veader were alone — for once — and she broke down in tears. There was something he should know if he wanted to marry her. She was guilty. Stained. Possibly an adulteress.

She took a breath and went back to the beginning, the first day of freshman year at a suburban Baltimore high school. Her science teacher, a married man in his 40s, looked up from his notes and stared into her eyes.

Later, he would tell her that when she walked into his classroom, he had a revelation: “God said, ‘There’s your wife,’ ” Grimm, now Johanna Veader, recalled.

The Banner is not naming the pastor at the request of Johanna Veader, who fears retaliation.

She was smart and driven, a perfectionist who dreamed of becoming a U.S. senator. But soon her life revolved around the teacher’s off-campus Bible study group. Her parents, conservative Baptists, were pleased. The teacher was wooing them, too, and convinced them to host the club. He urged them to make the hourlong drive to Baltimore to attend his church, Greater Grace World Outreach.

Within months, the church filled the family’s free time. Two services on Sundays — morning and evening — and one on Wednesdays. On Friday nights, a marathon Bible study session at their home that stretched until midnight. Saturdays were for passing out church literature around the city.

At first, it felt great.

“I was getting a lot of approval,” said Johanna Veader, now 34. “I had clear rules to follow to be seen as perfect.”

Following God meant making sacrifices, so she began to cut ties with friends who did not attend Greater Grace, even those who were fellow Christians, just as Carl Stevens instructed his earliest followers. “People were either Godly or worldly,” she said. “There was no in-between.”

The teacher became founding pastor of a Greater Grace offshoot nearby. He spent hours at the Grimm family’s home, locked away in a bedroom with Johanna, preparing his homilies. In these private moments, he would kiss her face and hold her hand, she said.

“He would touch my waist and hips and ask me if I thought about sex,” Johanna Veader recalled. “He told me hips are the most attractive part of a woman’s body.”

In emails reviewed by The Banner, the pastor repeatedly called Veader “Sweet Pea” and professed his love for her when she was 16 and 17. He urged her not to date and not to have intimate relationships with others. The pastor wrote that he prized the “closeness we have,” and that he found it “painful” to be away from her.

“You are perhaps the most amazing woman I have ever met,” he wrote in one email. “I’m so grateful that you are my Johanna. I love you.”

The pastor conceded that, “By the world’s standards you should not have the relationship you have with me.”

Johanna Veader said the pastor also sent her instant messages, which he instructed her to delete. But one day, her parents saw their conversations and realized that their pastor was declaring his love for their daughter, she recalled.

Her parents told her to avoid being alone with the pastor, though the family continued attending services at his church, she said.

But Johanna Veader was roiled by guilt, shame and confusion.

“It’s one thing to abuse. It’s another thing to abuse and pretend as if you’ve got God’s signature on your behavior,” said Johanna Veader. “He used my faith in God against me.”

Matt Veader reassured his fiancée that it was not her fault. They should go to church elders, explain what happened and ask for the pastor to be disciplined.

“These are good men,” Matt Veader told her. “They’re going to believe you. They’re going to help us.”

$6.6 million in donations, and a trial

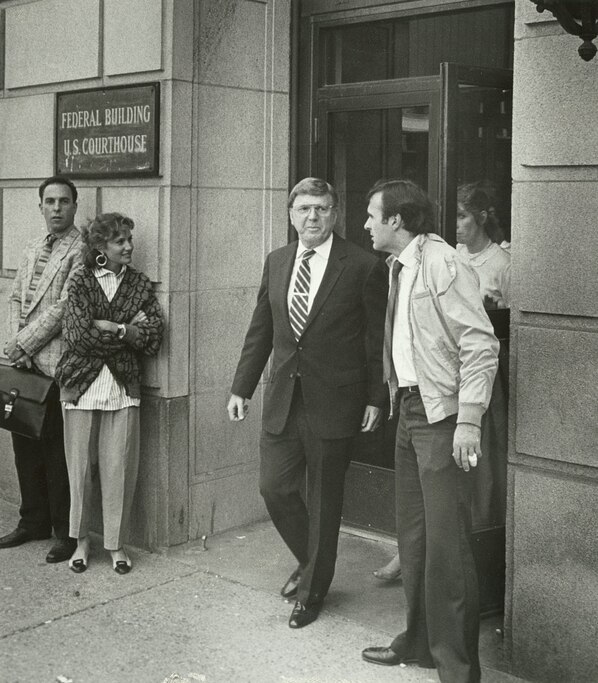

Good men. Holy men. That’s how Betsy Dovydenas had thought of Carl Stevens and his church bookkeeper. They persuaded Dovydenas, whose wealthy father ran the Dayton-Hudson retail chain, which later became known as Target, to support their work in the church.

Stevens and his assistant instructed Dovydenas in the early 1980s to make frequent financial gifts — and hide them from her husband. They asked her to rewrite her will to make the church — not her husband or children — her main beneficiary.

It was only after relatives and a cult exit counselor staged an intervention that Dovydenas realized she had been brainwashed. In 1986, she sued to get her money back — $6.6 million.

Lawyers for Dovydenas said Stevens had used some of her money to outfit a bedroom in his vacation home with floor-to-ceiling mirrors and a vibrating bed. Stevens also bought equipment that seemed better suited for an espionage ring than a church: a polygraph, an anti-bugging device, a voice stress analyzer, a bomb sniffer, a concealable microphone and a briefcase recorder.

The federal judge ruled in Doydenas’ favor and called the case “an astonishing saga of clerical deceit, avarice, and subjugation.”

In a recent interview, Dovydenas said she was intrigued by the church because the services were lively and the pews were filled with young families like her own.

“The experience was like getting high and letting go of something. Like getting tipsy and losing inhibition,” she added. “It wasn’t that I believed in the teachings, rather that I suspended my belief in reality.”

Stevens insisted he had done nothing wrong, and made a decision that would change the lives of thousands of his followers. He closed The Bible Speaks in Massachusetts and set his sights some 300 miles away — in Baltimore.

The decision to follow Stevens was easy, explained Taylor, one of Stevens’ former secretaries. “We were told: you have one pastor for a lifetime, and that’s God’s gift to you.” she said.

Throngs of cars with Massachusetts license plates began appearing in eastern Baltimore County in 1987. Church members crammed into apartments in Perry Hall and Fullerton; some camped out in sleeping bags behind a shopping center on Route 1 or buses parked in fields. Veader’s parents were among them, crowding into another family’s home until they found a place of their own.

The church was renamed and incorporated as Greater Grace World Outreach with services in a Holiday Inn ballroom, a former funeral parlor and a Teamsters hall as the congregation sought a permanent location. It held “blitzes” in which members swarmed over public-housing projects, the Inner Harbor and even Baltimore’s red-light district, looking to proselytize.

Baltimore’s established religious groups were wary. Several Catholic and Episcopal priests distributed flyers urging their congregations not to let members in their homes. The Cult Awareness Network, a nonprofit group that identified high-control religious organizations, led protests at Armistead Gardens. But as the years rolled by, people’s memories of the scandal faded.

For 17 years, church members quietly built Greater Grace in a former shopping center on Moravia Park Drive. In 2004, when Stevens, the head pastor, began to deliver rambling, incomprehensible sermons, members shared concerns on an online message board that Stevens was addicted to painkillers and alcohol. The church was also roiled by allegations that church leaders had paid off an angry husband to cover up an adulterous affair by a prominent clergy member, The Baltimore Sun reported at the time.

The church’s board of elders, a group of senior pastors, ousted Stevens in March 2005 and sought to reform the church’s policies on accountability and pastoral discipline.

Stevens was ultimately replaced by one of his long-time deputies, Thomas Schaller. Around the same time, more than 80 pastors broke with the church, frustrated by what they believed was a lack of commitment to the reforms.

Unlike his predecessor, Schaller was soft-spoken with a gentle demeanor. An early convert of Stevens, he had spent decades building outposts of the church in Finland and Hungary. He was a peacemaker, a sober leader for a new era.

“We will work out our problems, gain trust, forgive, pray, and go forward. I believe God is with us,” Schaller wrote in a letter to pastors.

Forgive and move on

Shortly before Thanksgiving 2015, Matt Veader sat down with Schaller in the back of the church cafeteria. For two hours, he pleaded with Schaller to punish the pastor who had groomed his wife.

Schaller said the young couple needed to forgive and move on, Matt Veader recalled.

The next day, as Matt Veader listened to the church’s radio program, “The Grace Hour,” he was shocked to hear Schaller rehash this conversation. While he did not mention the Veaders, or the pastor, he repeated his comments on forgiveness and moving on. A few days later, Schaller returned to these themes at a Sunday service.

“Somebody said to me, ‘Why don’t you deal with this person?’ ” Schaller said from the pulpit. “I said, ‘God can deal with them.’ ‘Yeah, but you’re in authority. You’re responsible for it.’ I said, ‘I don’t really know all that’s involved. I don’t know all the things.’ ”

Tears running down his cheeks, Matt Veader stood up and walked out.

Not long after, Steven Scibelli, a senior pastor and vice president of the church’s board of elders, called Veader, vowing to get to the bottom of the situation. Veader forwarded him one of the many inappropriate emails the suburban pastor had sent his wife when she was an underage teen, eight years earlier.

Scibelli appeared shocked, and told them, “I’m going to take his ordination so fast you’ll be able to smell the smoke,” Matt Veader recalled.

If Greater Grace did indeed revoke his ordination, it did not keep him from the pulpit. He continues to preach.

Outside his church one recent Sunday, the pastor denied wrongdoing. “I can say categorically that nothing inappropriate has taken place,” he said, blaming the allegations on “personal animus.”

At Greater Grace’s headquarters, a church official asked reporters to leave the property and refused to accept a letter detailing allegations of abuse and the church’s handling of them.

Scibelli also declined to speak with a reporter when reached by phone. “I have no interest in talking about this situation,” he said before hanging up.

The Veaders left Greater Grace in 2016. Some of their relatives, who had also grown disillusioned and left, were elated. Other family members feared they were headed for trouble.

But the couple knew leaving the church was the first step toward healing.

Johanna Veader pulled up a list of symptoms of complex PTSD and realized she had nearly every one, including panic attacks, uncontrollable shaking and nightmares. She and her husband began trauma therapy, and eventually Matt Veader decided to study to become a therapist himself, one who specializes in helping those with religious trauma.

Johanna Veader began working for a rape crisis center, directly across from the high school where she met the pastor. “I came back to that part of myself that wanted to be a senator, that wanted to have a powerful voice,” she said.

The couple shed the Christian identities that had been central to their lives and rebuilt their marriage.

In 2020, a few months after the bonfire, the couple welcomed a baby. As the new family hunkered down amid the pandemic, Matt Veader was haunted by the abuse allegations. Another former Greater Grace member had told him about FactNet, a now-defunct website about cults and controlling religious groups.

During one long night up with the baby, Matt Veader typed “FactNet” into an internet archive and began digging through old posts about Greater Grace.

“I am… a woman who was forcefully raped by someone I trusted in a church I belonged to. And the rape didn’t brutalize me nearly as much as the silence and shame that was poured on me. "

“I know firsthand of a child that was molested at Camp Life by a young man in charge of some activities there. And yes, the authorities were notified but it was a ‘he said, she said’ thing and the ministry actually defended the molester. Disgusting but true.”

An evil report

An evil report, that’s what church leaders called anything that reflected poorly on them or the church, former Greater Grace members said. It was a sin to criticize pastors or tell stories of their misdeeds. A sin to see, hear or read an evil report.

The 1987 “60 Minutes” segment in which Diane Sawyer interviewed Betsy Dovydenas was such an evil report. A 1981 report from the Christian Research Institute, a nonprofit that studies Christianity, which called the church “cult-like” was one too. So were the allegations on FactNet.

FactNet was a portal to a different era in the church — and yet Matt Veader and other former church members were still grappling with the same question all these years later: How could church leaders have turned a blind eye to abuse?

Amid the sea of old messages was a mandate.

“We need to do all we can to let the victims know that we care, that we believe them, that they can get free,” one user posted. “We must do whatever it takes to make their hell stop.”

Deeply shaken, he called a few friends from the bonfire. The problem was even larger than they had suspected. The friends started reaching out to others who had left the church. Soon people were contacting them, sharing stories of witnessing, hearing about — or surviving — abuse at Greater Grace.

Somehow, without intending to, they had started an investigation.

“There were times when it felt like we were just following the evidence, times where it felt like we were standing up for the people we loved, and times where it felt like a little bit of both,” Matt Veader recalled.

The group decided to document sexual abuse in the church and how it was concealed. They wanted survivors to know they weren’t alone. They wanted abusers, and their protectors, held accountable. They wanted to bring secrets to light.

They also wanted to give their team a name. So, as they had been taught, they turned to Scripture.

In the Book of Matthew, Jesus issues a warning for those who harm children: “If anyone causes one of these little ones to stumble, it would be better for them to have a large millstone hung around their neck and to be drowned in the depths of the sea.”

That’s what they would be. The force dragging down people who hurt children.

They were The Millstones.

Read part II: Web of megachurch sex abuse leads to a trusted pastor and his sons

Resources for survivors of sexual assault & religious trauma

- MCASA: Maryland Coalition Against Sexual Assault.

- RAINN Get help 24/7. Call the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network by dialing 800.656.HOPE.

- The Trevor Project: A nonprofit focused on preventing LGBTQ suicide. Visit TheTrevorProject.org or text 678-678.

- The Reclamation Collective: A network of therapists who specialize in religious trauma. Visit ReclamationCollective.com for more.

Comments

Welcome to The Banner's subscriber-only commenting community. Please review our community guidelines.