This story is part of a partnership with The Baltimore Banner and BmoreArt that will provide monthly pieces focusing on the region’s artists, galleries and museums. For more stories like this, visit BmoreArt.com.

Before jumping into the annual ritual of proclaiming the best art exhibits of 2024, I want to clarify what makes one great. For me, the element of surprise is key. In some cases, a sense of wonder comes from the skill and labor of the art itself. From others, it comes from inspired curation and exhibition design, where place and time is intentionally integrated to create emotional connection.

Baltimore has an incredible array of museums, but until recently, they rarely exhibited works by local artists. Thankfully, this has begun to change as larger institutions recognize the high quality of work created here and the audiences that those artists draw. You’ll see some of that work reflected in my picks.

The exhibitions that stood out to me were also groundbreaking, culturally relevant and made me feel more connected to the place and time where I live. They managed to capture, articulate and confront our collective past, present and future in innovative ways, and their delivery was decadent and congenial, rather than didactic.

As Baltimore heads into a new year, I hope you’ll take a moment to celebrate these success stories and remember that the arts are not a luxury nor entertainment, but a necessity for a city that needs us.

‘Joyce J. Scott: Walk a Mile in My Dreams’ at the Baltimore Museum of Art

It’s difficult to pick just one excellent exhibit shown at the Baltimore Museum of Art in 2024. The museum created a museum-wide survey of Indigenous artists, exhibited locals Jackie Milad and Nekisha Durrett alongside Fred Wilson, and is currently host to an incredible homage to Baltimore home health workers, LaToya Ruby Frazier’s “More Than Conquerors.” The institution has answered in recent years the question of what it means to be Baltimore’s museum and share the best the city has to offer with the world. That’s why it has been so gratifying to see the BMA invest significantly in MacArthur genius Joyce J. Scott, our culture queen and “round the way girl” from Sandtown; our bard of bawd, improvisational jazz singer, and prolific purveyor of beauty.

Read More

Anyone who saw Scott’s 50-plus-year retrospective “Walk a Mile in My Dreams,” whether local visitor or out-of-towner, was offered an unparalleled, unprecedented, groundbreaking and generally mind-blowing experience. Working with BMA curator Cecilia Wichmann, Scott seamlessly captured Baltimore’s grit and swagger, aesthetic prowess and innovative use of materials. She unflinchingly explores the most overt violence, rage and racism, as well as the most intense aspects of maternal and romantic love. Scott’s show affirmed that this city is home to great artists because it provides the freedom, space, urgency and community necessary to make it so.

‘Ethiopia at the Crossroads’ at The Walters Art Museum

It’s not fair to compare Baltimore’s two major museums, but it’s also impossible not to. While the BMA is a frenetic hotbed of activity and energy, the Walters is a quiet space for contemplation. There is one main dedicated space for changing exhibits, but it’s located in a basement-level bunker that offers none of the power or charm of the rest of the building and its generally static works.

One exhibit that stood out from the rest was “Ethiopia at the Crossroads,” curated by Christine Sciacca with co-curatorial consultation from Tsedaye Makonnen, a contemporary Ethiopian American artist based in Washington, D.C. Combining Sciacca’s deep research and the museum’s unique holdings of Ethiopian art with the curatorial insight of a living artist proved to be the catalyst that elevated this exhibit into groundbreaking territory. Works by Betye Saar and Helina Metaferia were placed alongside centuries of historical pieces, enlivening both into a comprehensive and challenging conversation about the way history is shared and constructed.

“Crossroads” was one Walters exhibit of the past decade that achieved significant national recognition via a Washington Post review and an award from Apollo magazine, both well-deserved. The show strategically included the growing Ethiopian immigrant community from the Baltimore-Washington region, and placed the work of contemporary Ethiopian, African and African American artists into pivotal and central positions within a larger historical context.

This infusion of energy from local and global contemporary art and artists, not as a programmatic footnote or singular accent in an exhibit but as a central operating principle, exemplifies an approach that is needed to animate the entire museum and bring it back to life.

‘Black Woman Genius: Elizabeth Talford Scott—Tapestries of Generations’ at the Reginald F. Lewis Museum

One positive trend in 2024 was a major initiative linking eight different museums together to celebrate the work of another trailblazing artist from Baltimore: Elizabeth Talford Scott, mother to Joyce. At the Reginald F. Lewis Museum and brilliantly curated by Imani Haynes, “Black Woman Genius: Elizabeth Talford Scott—Tapestries of Generations” was a powerful, cross-generational conversation between 10 Black women fiber artists from the mid-Atlantic region.

The show featured contemporary works by Kibibi Ajanku, Aliana Grace Bailey, Aliyah Bonnette, Mahari Chabwera, Joan M.E. Gaither, Murjoni Merriweather, Glenda Richardson, Joyce J. Scott and Nastassja Swift, three generations of artists influenced by Scott presenting a generative and multifaceted approach to fiber-based storytelling. It also generated an influx of regional foot traffic to the museum, especially from artist communities wanting to see themselves reflected through three generations of fiber-based artists.

Although Talford Scott passed away in 2011, she spent a lifetime making experimental fiber-based works that were not necessarily recognized as art until the end of her life. In this exhibit, her persistence as a trailblazer is celebrated, and her vast impact on an entire community of Black women working in fibers is evident in every gorgeous thread, stitch, quilt and cloth, and was punctuated with video, photos and inspirational quotes.

Josh Kline’s ‘Capture and Sequestration’ at art hall

Baltimore’s newest contemporary gallery, art hall, is located in a former Hells Angels biker bar in Old Goucher. Beautifully renovated, the space features work by significant international artists, scaled purposefully for a Baltimore audience. It opened with an exhibit of Antoine Catala, which was followed by work from Josh Kline. The art hall show marked the first time Kline’s “Capture and Sequestration” videos were shown as an immersive, four-channel presentation.

Downstairs in the video gallery, four objects burn on four giant screens: sugar, tobacco, cotton and oil — the commodities that propelled America into a global superpower that dominates the globe economically, culturally and militarily. These are also the materials that caused the enslavement of African people, the theft of Indigenous land and the industrial revolutions of the 19th and 20th centuries. As the fires progress, you realize you’re watching the burn happen in reverse so the objects gradually become more discernible: a box of Domino sugar, a pack of Marlboro cigarettes, denim jeans and a red plastic gasoline can.

The view segues into a smoke-filled blue sky that is sucked into pipes; in another scene hands wrap up the four different objects in rope, chains and plastic and neatly bury them in the ground. The entire loop lasts a few minutes, but moves at a clip that keeps your interest. In the gallery upstairs, each of the four buried bundles are displayed on Velveeta-orange pedestals under orange lights, reminiscent of traffic cones and hazmat suits.

This show powerfully reminds us that artists see the world through a different lens and cadence. Even the most troubling or impossible scenarios can be transformed into something compelling and beautiful. What if we could magically suck the carbon out of the air and safely keep it underground? What if we could reverse the climate crisis and then apply a similar approach to other toxic issues plaguing humankind? Kline depicts “carbon sequestration,” an experimental process where carbon dioxide and other harmful substances are captured and stored deep underground, in order to present a solution for climate change — literally out of our own ashes.

‘Bearing Witness: A History of Prints’ and ‘NOW: Collaborations by Joyce J. Scott and Tim Tate’ at Goya Contemporary Gallery

Best known for her beaded sculptures, elaborate jewelry, installations, performances and quilts, Joyce Scott has also long been a prolific printmaker. Shown concurrently to her BMA retrospective, “Bearing Witness: A History of Prints” at Goya Contemporary offered proof that Scott’s graphical sensibilities are as strong as her tactile proclivities, featuring 30 works on paper made over the last 50 years. I’m sorry to keep bringing up Scott, but 2024 really was her year and there’s no good reason NOT to celebrate it, especially because she’s the kind of artist who brings others along with her, working collaboratively and inclusively.

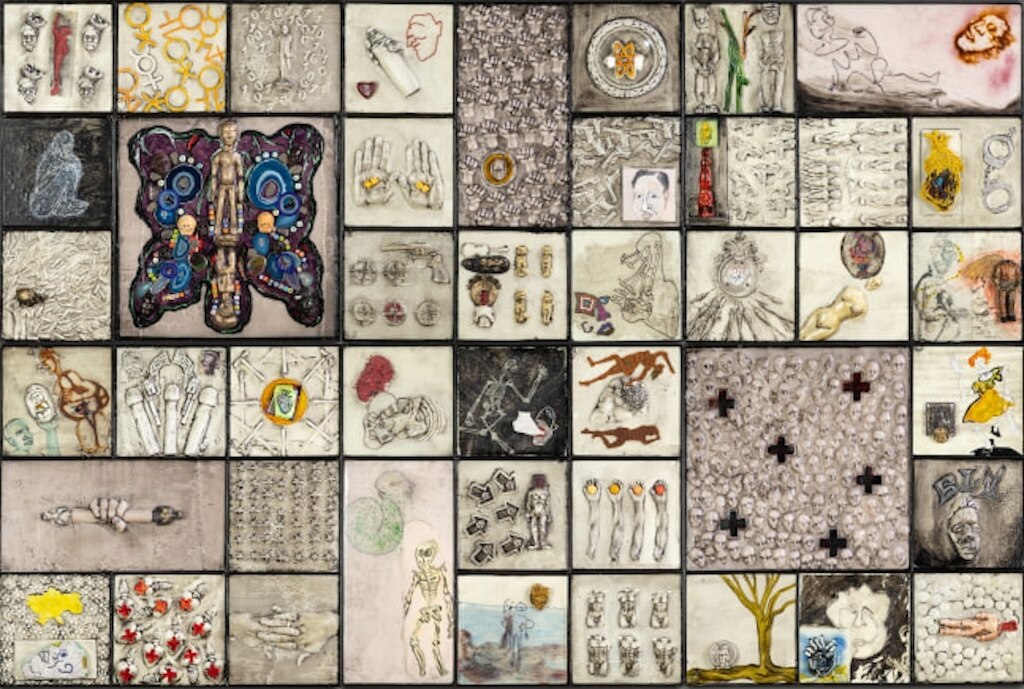

In the smaller, back gallery at Goya, “NOW: Collaborations by Joyce J. Scott and Tim Tate,” co-founder of the Washington Glass Studio, collaborative glass works presented the same aesthetic boldness, political acuity and impish wit that animate any medium Scott touches. The largest work — a collaborative wall mosaic where glass squares were embedded with beads, metal, wood, and other found objects — chronicles a news cycle of American and global issues from 2020 on in symbolic, cheeky and deadly serious terms.

To read the full story with additional top exhibits of the year, including shows featuring Bria Sterling-Wilson and Monica Ikegwu, check out “Ten Best Baltimore Exhibitions of 2024″ at BmoreArt.com.

Comments

Welcome to The Banner's subscriber-only commenting community. Please review our community guidelines.