This story is part of a partnership with The Baltimore Banner and BmoreArt that will provide monthly pieces focusing on the region’s artists, galleries and museums. For more stories like this, visit BmoreArt.com.

Why are paintings the most highly valued objects in an art auction? Why is glass sculpture considered corny by art snobs?

For most of my lifetime, I have observed a clear distinction between art and craft, especially in museums. Although the craft community tends to be more expansive and inclusive, it’s been quite rare until recently for museums to exhibit paintings, drawings and sculpture alongside furniture, garments, dishes and jewelry — no matter how exquisitely or conceptually made. Lately I have found myself more and more drawn to the “decorative arts,” not just because these tend to be decadently beautiful objects, but because we have underestimated their ability to carry a serious message.

There are four museum exhibitions on display this month that purposefully blur the hierarchical boundaries between genres and time periods, material and meaning. All of the shows question the relevance of an art history that has largely elevated white, academically trained men in favor of an approach that invites more nuance to all kinds of creative expression.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

More than any other player in the arts ecosystem — whether it is fair or not — museums are tastemakers, and have the power to elevate historically undervalued art and artists. I invite you to take advantage of their curatorial expertise this October and immerse yourself in spaces full of incredible objects that act as containers of remarkable stories. There are a number of excellent museum shows in the region worth your time and energy. In particular, though, there are a few smaller museums exhibiting relevant, innovative work, as well as a major museum undergoing a groundbreaking, sitewide experiment.

‘Fragile Beauty: Art of the Ocean’

Hillwood Estate, Museum & Gardens

4155 Linnean Ave. NW, Washington, D.C.

Through Jan. 5

What do a historic whalebone corset, a contemporary ceramic sculpture by Morel Doucet and a pair of jewel-encrusted Louboutins have in common? The ocean — and the late Marjorie Merriweather Post. Considered one of the wealthiest women in America during her lifetime, Post was a prodigious collector, philanthropist and businesswoman. Her home in Northwest Washington — now Hillwood Estate, Museum & Gardens — is a vast delight of decorative and fine arts, including: 18th- and 19th-century Russian and French art, House of Romanov Fabergé eggs, Sèvres porcelain, French furniture, jewelry by Harry Winston and Cartier, tapestries, exquisite gowns and one of the best orchid collections in the country.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

In “Fragile Beauty: Art of the Ocean,” the decorative arts powerhouse proves functional objects like furniture, garments and jewelry can be every bit as topical as fine art. In this rich, deep blue treasure box of an exhibit, a giant oil painting of a roiling ocean boasting allegorical figures sets a grand tone. The painting, “Treasures of the Sea,” is a 1900 copy of the 1870 original by Austrian painter Hans Makart, which was owned by Post’s father, C.W. Post. As you would expect, other seascapes are also featured, but so are objects made of coral, pearl, tortoiseshell and ivory. Luxuriating in the rich tactility of these materials can feel jarring when you consider the role of human exploitation.

Ships, mermaids and seashells abound in this exhibition. Strategically placed contemporary works by Courtney Mattison and Théo Mercier, Maryland Institute College of Art graduate Doucet, and designer Christian Louboutin are placed in deliberate proximity to historical objects, emphasizing their commonalities. Doucet’s intricate ceramic sculpture serves as a testament to the sea’s timeless spirituality, while Mattison and Mercier’s works illustrate the ocean’s vulnerability to climate change and pollution. They offer hope in the use of cleverly recycled and sustainably sourced materials, while asking questions about how best to protect and preserve the ocean’s bounty for future generations.

On Oct. 16, join Doucet and gallerist Myrtis Bedolla in an engaging and insightful conversation moderated by Wilfried Zeisler, chief curator and deputy director of Hillwood.

Connie Imboden, ‘Endless Transformations: The Alchemy of Connie Imboden’ and Mark Kelner, ‘New American Landscapes’

American University Museum at the Katzen Arts Center

4400 Massachusetts Ave. NW, Washington, D.C.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

Through Dec. 8

These two solo exhibitions by regional artists could not be more different, but both address historic genres — landscape and portraiture — in brazen and astounding ways.

The dozens of photographs in Connie Imboden’s sweeping survey pulse with a Caravaggio-esque chiaroscuro approach to portraiture, in which waning figures emerge dramatically into the spotlight from velvety black darkness, like actors on a stage. Reminiscent of Tim Burton’s unearthly but graceful style, Imboden’s photographs also have much in common with Sally Mann, the contemporary portrait photographer who uses antiquated photographic glass plates and a wet collodion process to create a distorted result.

In Imboden’s case, her technique has been intuitively honed and all of her images are created in the camera, not by a computer or an experimental printing process. Imboden arrives at her images by shooting through all manner of screens and surfaces and employing multiple light sources, in collaboration with her models. Her characters present themselves as layered fragments shot through scratched plexiglass and silk or rendered bizarre by underwater reflection, asking thoroughly contemporary questions about identity, gender and queerness in a spicy carnal language. Referencing Jungian archetypes and mythological creatures, Imboden’s images are simultaneously tender and violent, intellectual and intuitive, universal and intimate.

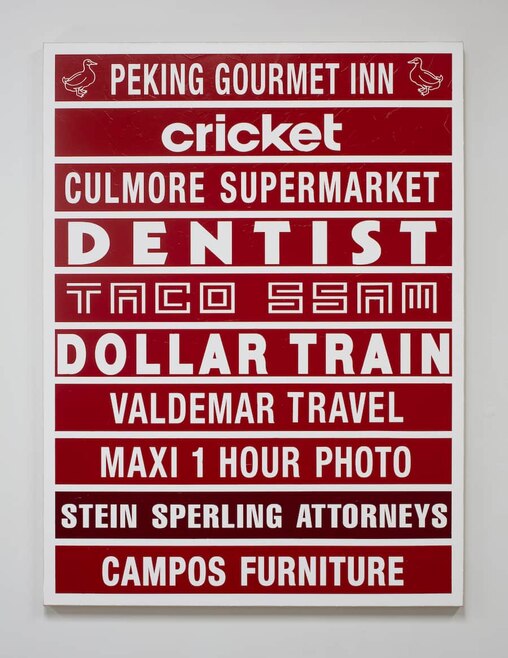

In a nearby but unrelated exhibit, Mark Kelner mines the essence of the suburban landscape into deadpan renderings of strip mall signage in “New American Landscapes.” These glyphs offer perhaps the least sophisticated and explicitly transactional graphic design, but they pulse with a humble, capitalistic energy, as if Ed Ruscha was based in New Jersey rather than California.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

Rendered in acrylic paint on canvas and composed in stacked compositions with other signage, text and typography meld into multifaceted mercantile statements about American identity and existence, economic limitations coupled with idealism and belief in hard work. Viewed collectively, Kelner’s presentation of generic signs for vape shops, bars and tax services coalesce into a new American landscape; these paintings pulse with totemic commercial energy, both ironic and earnest.

‘Preoccupied: Indigenizing the Museum’

Baltimore Museum of Art

10 Art Museum Drive, Baltimore

Through Feb. 16

Rather than just one exhibit, “Preoccupied: Indigenizing the Museum” is an expansive network of nine exhibitions that extends to all aspects of the museum, including public programs, staff training and a specifically designed approach to wall text. This seems like an appropriate response to the project’s ambitious goal, which is to address “the historical erasure of Indigenous culture by arts institutions while creating new practices for museums.”

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

Going far beyond the well-intentioned gesture of a native land acknowledgement — that near-ubiquitous panacea for cultural organizations with colonial guilt — this BMA initiative puts significant resources behind its values, literally transforming the entire museum to accurately reflect a vast and diverse trove of cultural achievement. As a singular statement, “Preoccupied” makes an airtight case that Native people in America have created works of art as relevant and powerful as any other segment of the art historical canon. It includes archival and functional craft objects alongside contemporary film, painting, sculpture, photography and installation, intentionally blurring historical boundaries between fine and decorative art, and encouraging audiences to appreciate each object on its own terms rather than viewing it as part of a genre or tradition.

“‘Preoccupied’ radically centers Native perspectives in a space that has often overlooked or erased that community: encyclopedic museums,” said Dare Turner, co-creator of the project and curator of Indigenous art at the Brooklyn Museum, in a curatorial statement. “It challenges all museums to interrogate their colonial roots and make space for new ways of thinking, learning, and being.”

Largely unrecognized in American museums, this massive trove of Native excellence is presented in a manner befitting its sophistication and craftsmanship. The range of objects assembled, the research and care that went into the network’s organization and the variety of community outreach and engagement methods for “Preoccupied” offer a model for building community with and around underrepresented and marginalized communities in a way that centers their voices, rather than exploiting them. This framework for collaborative exhibition design is groundbreaking and valuable — one that can carry the BMA and others forward in an intentional, equitable way.

Han Cao, Jennifer McBrien, Michael-Birch Pierce and Stacey Lee Webber, ‘The Subversive Thread’

Academy Art Museum

106 South St., Easton

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

Oct. 22 through March 30

If you have never gone to the Academy Art Museum in Easton, add this spot to your next Eastern Shore itinerary. Founded originally as the Academy of the Arts in 1958, the institution became accredited by the American Alliance of Museums in 2003 and changed its name to its current iteration.

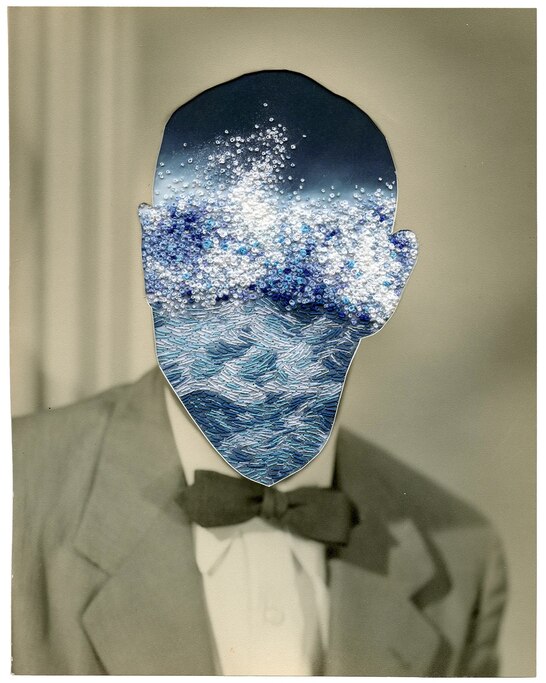

Designed to provoke and question established boundaries around fiber and thread art, “The Subversive Thread” features art by Han Cao, Jennifer McBrien, Michael-Birch Pierce and Stacey Lee Webber. All four artists employ textiles and techniques traditionally considered unconventional in the fine art world, such as needlework and embroidery, a benchmark for cultured women in the 18th and 19th centuries. Even today, needlework is often viewed as a kitschy craft or hobby, but feminist-based fiber art is having a big moment in the contemporary art market. When artists employ traditionally feminine techniques to confront and subvert stereotypes, the element of contrast between the message and materials can lend a powerful punch of surprise.

Although the artists in this exhibit use needlework to present contemporary messages, they rely on other materials as well for evocative storytelling. By sewing and embedding found photographs, American currency, leather and sequins, the artists question the traditions we hold around fiber art and thread — positing that art and craft have more in common than divides them.

In Cao’s work, whimsical combinations of found photos are embellished with textural needlework, transforming them into iconic and precious visions. McBrien’s images are centered within embroidery hoops, where birdlike female figures strike powerful poses atop vintage toile in varying states of deterioration. Pierce’s embroidery emphasizes artifice and authenticity in personal identity, rendered fantastical through additional elements of fashion and costume. And Webber’s embroidery is defiant and controversial, rendered atop American legal tender, which is illegal to “mutilate, cut, deface, disfigure, perforate, or otherwise damage” according to 18 U.S. Code section 333. Viewed altogether, these artists ask questions that engage viewers through expert craftsmanship and playful combinations, elevating the cultural and artistic value of a medium that is widely beloved, perhaps everywhere except for museums — until now.

Comments

Welcome to The Banner's subscriber-only commenting community. Please review our community guidelines.