Sitting on the grass in Green Mount Cemetery, Robert Murch wondered what the hell he had gotten himself into.

For 15 years, Murch, founder of the Talking Board Historical Society — a group of spirit board collectors, historians and aficionados — had searched for the lost grave of Elijah Jefferson Bond, the man who patented the Ouija board. His journey to find Bond’s final resting place and honor him with a Ouija-themed gravestone had taken him to hundreds of public and private cemeteries and archives across the country, to no avail.

Now, however, he was closer than ever.

In April 2008, Murch listened to loud booming as a caretaker pounded a copper sounding rod into the ground.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

The sound the rod makes changes depending on whether it’s hitting disturbed soil or tightly packed earth. Murch was told they would “hear a very big difference” if a grave was found.

He was accompanied by Kathy Fuld, the bemused granddaughter of William Fuld, the man who, by the early 20th century, had made over $1 million marketing and selling Ouija boards in factories across Charm City.

Murch said he began to have doubts.

“They’re pounding this through this guy — like his remains being disturbed very loudly, very publicly,” Murch said. “So every time that boom, boom, every time, every time they hit it ... it’s like, ‘Holy shit. What have I done?’ This is chaos.”

Boom, boom, boom.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

And then, walking over the hill, as if on cue, appeared filmmaker, writer and Baltimore legend John Waters.

Searching for Elijah Jefferson Bond

“There’s no [Ouija] story without Baltimore,” Murch said.

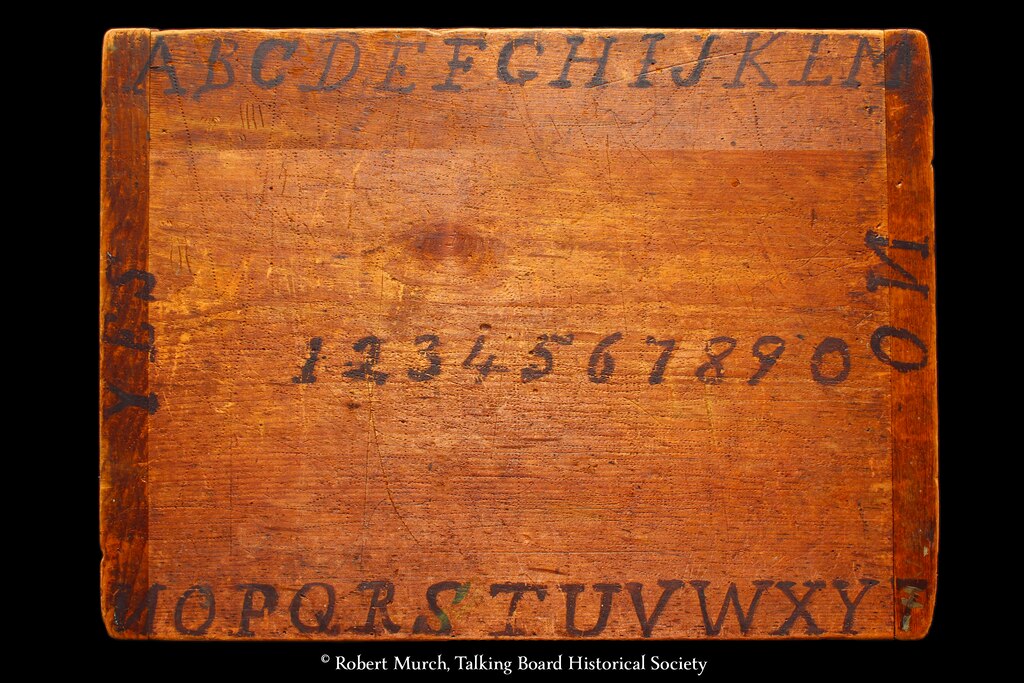

Before it got its ‘Ouija’ moniker, the mysterious talking boards — also called spirit boards or witch boards — were largely homemade.

Baltimore businessman Charles Kennard moved from Chestertown, on the Eastern Shore, to Baltimore in 1890 and began selling real estate. While in Chestertown, Kennard had read about people making boards with letters and numbers written on them and using their hands to move a saucer or “planchette” (a piece of wood on casters) to spell out messages from the dead.

Spiritualism — the belief that the living could contact and converse with the departed — was in vogue in the late 19th century. So in 1890, Kennard formed the Kennard Novelty Company at 17 St. Paul St. to manufacture his talking boards.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

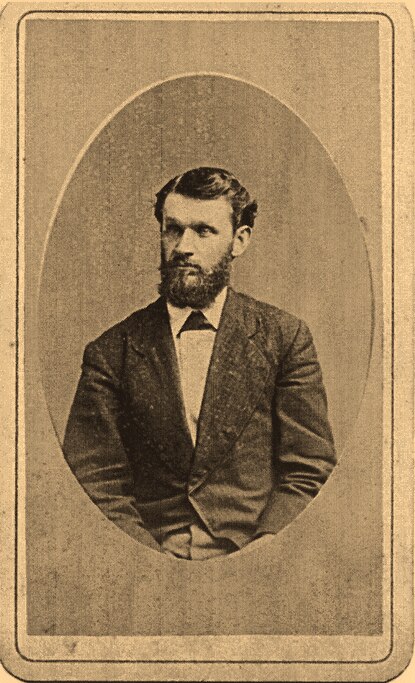

Next door to Kennard’s office was a former Confederate soldier and lawyer — Elijah Bond. And Bond was convinced Kennard’s invention would be a moneymaker. But he thought the board looked amateurish.

His redesign birthed “that classic Ouija look,” Murch said.

“The double arcs of the letters, the single line of the numbers, ‘yes,’ ‘no,’ ‘good night’ or ‘good bye.’ ... And he decides, ‘We’ve got to patent this.’ And that’s the beginning.”

‘Mother of the Ouija board’

But first, the board needed a name.

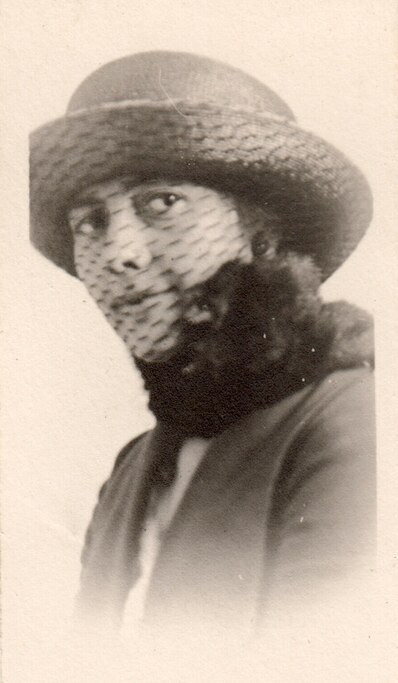

One night, Kennard and Bond’s sister-in-law, Helen Peters (later Helen Peters Nosworthy), a spiritualist and medium who was considered especially adept at using the board, met Bond in his room at 529 N. Charles St., now a 7-Eleven convenience store.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

Realizing they didn’t have a name for their product, they decided to ask the board what it wanted to be called.

Peters placed her hands on the planchette, opened up to the spirits, and spelled out the answer.

O-U-I-J-A

They asked what that meant.

L-U-C-K

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

They took that to mean “good luck,” and decided it was probably an Egyptian word (it wasn’t, but ancient Egypt was fashionable and mysterious at the time, so it stuck).

Now that the board had its name, thanks to Peters (who became known as the “Mother of the Ouija board”), it was time to get a patent.

(And if you happen to stop in the 7-Eleven on the corner of North Charles and East Centre streets, you can find a plaque proclaiming “Ouija was named here.” You can also see Peters’ personal Ouija board at the Witch Board Museum in Hampden.)

A ghostly patent

The patent office in Baltimore was not impressed.

Murch described the official’s bewildered response. “You’re saying you put your fingers on something, you ask a question, and it moves on its own to the answers?”

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

The patent filing was declined.

Undeterred, Peters and Bond traveled to the patent office in Washington, D.C.

According to family members who were told the story, and details from a file at the National Archives, Peters and Bond demonstrated the Ouija board at the national patent office.

It did not go well.

Peters and Bond kept getting passed up the bureaucratic chain, from one clerk to another, and finally to the annoyed chief clerk.

“So he walks in the room and says, ‘OK, you know, I don’t know you, and you don’t know me,’” Murch said. “‘If that contraption can spell my name, you get your patent.’”

With Peters wielding the planchette, the board did just that, Murch said.

“A very visibly shaken clerk gets up, very white, and says, ‘You’ve got your patent’ and cannot get out of the room fast enough.”

On Feb. 10, 1891, Bond was granted Patent No. 446,054 for the “Ouija or Egyptian luck-board.”

Sticky file cards — and a lucky find

In October 2007, Murch said he’d “had it,” and was exhausted after the years of searching for Bond’s grave. So he went to the spot in Green Mount where he thought Bond was likely to be buried — next to his wife, Mary, and their son, William.

“And I’m like, ‘Why won’t you tell me where you’re buried?’ ” he said, laughing. “Why is this such a problem?”

He then went to cemetery staff and asked if they could look through the massive card index of burial records. They said no — they had already done several fruitless searches — but told Murch he could look for himself, one last time.

As he flipped to the archive card for Bond’s son, Murch noticed it was thicker than the rest. He slowly picked at the edges of the card. And it peeled into two.

“Elijah Bond’s card was stuck to the back of his son’s. And there it says, ‘Elijah Bond was buried in this plot.’ ”

The records, though, were vague. There were three possible unmarked plots where the man who patented the Ouija board could have been buried.

And that’s how Murch ended up in Green Mount Cemetery six months later, as the copper sounding rod signaled the discovery of Elijah Bond’s grave just after John Waters wandered upon the scene.

A ‘fever dream’

“And about at that moment, when I’m probably thinking, ‘Wow, this is really bad,’ John Waters just like, comes over the little hill, walking at me,” Murch recalled.

“But I was thinking, ‘Oh, right, of course John Waters would walk up at the worst moment of my life. How embarrassing.

“And of course, [he] wants to know what the hell I’m doing. Why is this noise echoing all through here? Why is all this happening?

“He was there paying his respects to [actor and freak show performer] Johnny Eck, so that made sense to me — it’s like a minute walk from [Eck’s] grave.

Murch told Waters that he was looking for the body of the patentee of the Ouija board. “It’s like, this holy shit conversation ... I can’t believe any of this is happening now.

“And he’s kind of like, ‘Oh, I think this is cool.’ He did say that he really enjoys Baltimore’s weird history, and this was cool to walk up on.”

(Waters, in an email, said he does not remember details of the incident, but recalls the visit to Eck’s grave while accompanying his friend, Jeffrey Pratt Gordon, an Eck historian and collector.)

And then came an unmistakable sound.

Boom. Boom. Gong.

“The gong was different,” Murch said. “So we found it, and he [Waters] just kind of walks off and like, ‘See ya.’ And it was just one of those perfect moments where you were like, ‘What the hell just happened?’

“It’s like a fever dream. Do you know what I mean?”

Murch and the Talking Board Historical Society raised funds to commission and install a Ouija board gravestone on Bond’s burial plot in July 2008. It has become the most-visited grave in Green Mount Cemetery, according to Murch and Green Mount Cemetery staff.

Elijah Bond’s grave can be found in Green Mount Cemetery here. The plaque commemorating the naming of the Ouija board is located in the 7-Eleven store at 529 N. Charles St., and you can see Helen Peters’ Ouija board at the Witch Board Museum Baltimore in Hampden. You can also find out more information about Robert Murch and the Talking Board Historical Society. For matters from the Other Side, dust off that Ouija board in your attic.

Comments

Welcome to The Banner's subscriber-only commenting community. Please review our community guidelines.