Off U.S. Route 1 in Howard County, in the shadow of new townhomes and industrial-style apartments, a stone wall hides a forgotten little park.

The lawn here is pockmarked with depressions where, year after year, the bronze plaques are sinking deeper in the dirt. These are the graves.

There’s not much else. A battered old house, a collapsed barn, watchful stone buddhas. A black cat creeps through the tree line (honest). Stephen King might have written about this place.

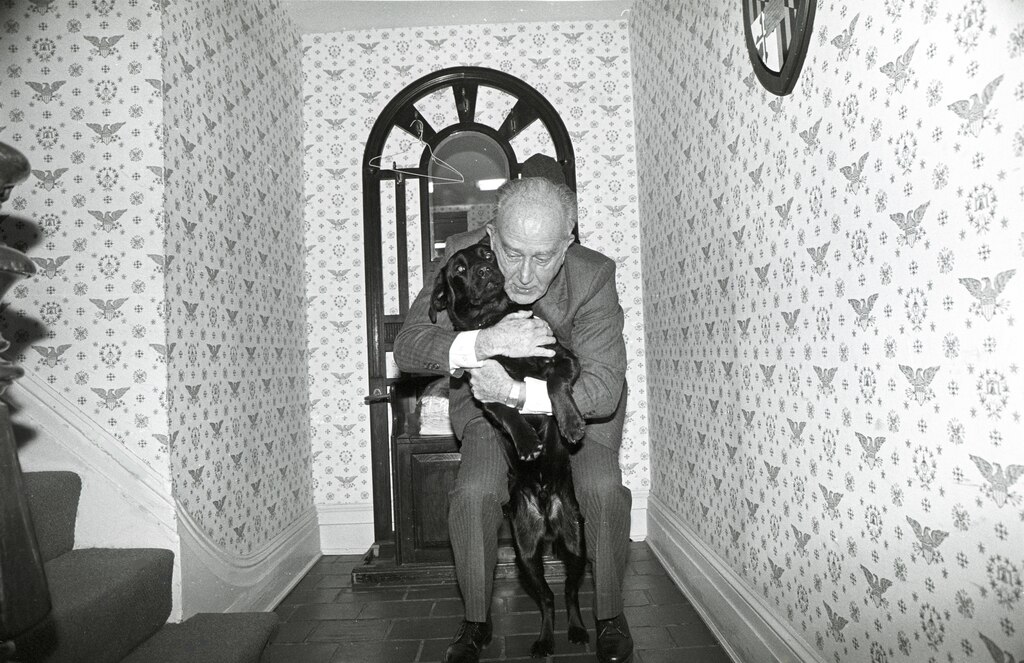

The little park was once the Arlington National Cemetery for our pets. Here’s where the late Gov. William Donald Schaefer laid to rest his lab, Willie II. It’s where the old Baltimore Bullets buried the team dachshund, Alex. Forget weeping angels. A red fire hydrant marks one dog’s grave.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

“Right about here,” says Candy Warden, standing at the rose garden in the center. “There was a sign on a post that said, ‘Mary Ann the elephant.’”

Warden leads a small volunteer group that works to maintain historic Rosa Bonheur Memorial Park and fend off development. Pets notable and ordinary — thousands of them, from pigeons to poodles — are buried in the park at the boundary of Howard and Anne Arundel counties.

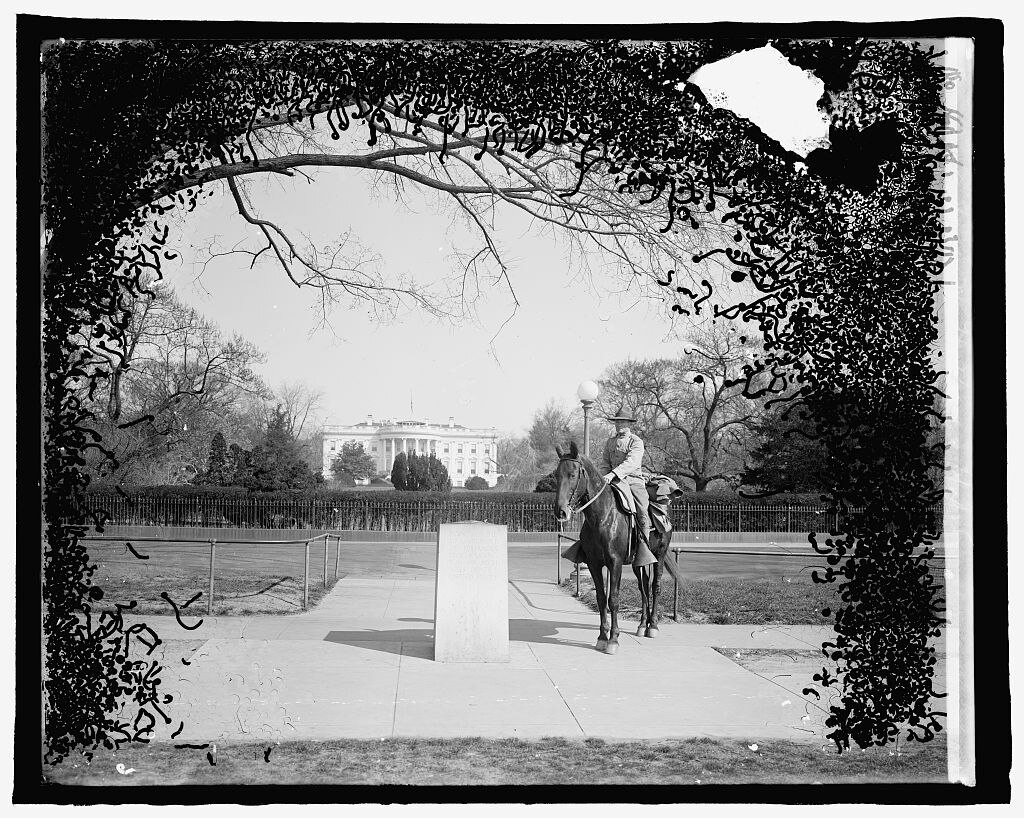

Here lies Gypsy Queen the horse. She traveled 11,356 miles under pack and saddle to reach every U.S. state and won fame for her endurance. She shares this eternal home with a Doberman pinscher named Rex, whose growl famously alerted U.S. Marines to a surprise Japanese attack in WWII. Dearly departed Pete the pigeon drank coffee at the breakfast table and became a Depression-era celebrity in South Baltimore. He died like a Methuselah at age 25. The headlines read, “World’s Oldest Pigeon.”

There are people buried here, too. Elizabeth Kirk-Anderson, who co-founded the Animal Welfare League of Greater Baltimore, interred at least 18 of her pets and her mother.

Despite its fame, the pet cemetery was clouded by legal trouble, mismanagement and scandal before it closed to burials two decades ago. Warden and the other volunteers don’t own the grounds, and they have watched new apartments and townhomes rise up around these eight acres. They worry Rosa Bonheur will be parceled off for new roads or a gas station.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

The volunteers also worry that the deceased, both human and animal, will be dug up and lumped together in the back like some mass burial.

Those fears were realized last December. They found memorial markers piled up, and earth turned over near the front of the cemetery.

Someone was moving graves.

The dearly departed

First, back to the elephant in the graveyard.

Mary Ann’s grand entrance to Baltimore in the 1920s was the culmination of a yearslong campaign by the city’s children. She was greeted with a reception committee, a brass band and streetcar parade in her honor.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

As Baltimore’s first elephant, Mary Ann remained the star of the zoo for two decades, her surly disposition aside, until the night she collapsed in her cage. They buried her with honors at Rosa Bonheur.

The cemetery traces to 1935, when Edward Gross, the criminal court clerk for Baltimore, was bereft over the death of his dog. Without a suitable burial site, he interred his loyal companion in a cemetery for people. The experience inspired him to open Rosa Bonheur Memorial Park, named for the 19th-century French painter of animals.

In the countryside 14 miles southwest of Baltimore, pets were interred with pageantry. Just picture the hearse, silk-hatted mortician and, say, a procession of schnauzers as they buried Fifi. The dead were treated to expensive metal caskets with satin liners, The Baltimore Sun wrote in 1939.

“The first encounter with death that people have is with their pets. My goldfish died or my cat died,” said David Zinner, who serves on a state advisory council for cemetery oversight. “How families handle those deaths leaves an impression on children about how you treat the dead, and gives us an opportunity to show them what it means to be respectful and what it means to value life.”

By the 1950s, the grounds held the remains of almost 3,000 pets. Owners traveled from as far away as Florida and North Dakota, The Sun wrote. The cemetery’s later owner eschewed the pomp and circumstance for a quiet dignity. Bronze plaques read with names such as Duke and Lady, Spunky and Tibby, Patches, Smokey, Inky, Zsa Zsa and Tiny Boy Pierre.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

A carousel of owners

William Green took over the cemetery in the late 1970s and marketed Rosa Bonheur as the only place in the world where people and their pets could be buried in adjoining plots. Whether true or not, the cemetery’s fame exploded. By 1985, The Sun wrote, the grounds held 100 people and 8,000 pets, with one plot reserved for a lion.

If a lion rests at Rosa Bonheur, that tale’s forgotten. There’s an old reference to Moses the monkey, too, but no other explanation. The cemetery records were lost amid a carousel of owners.

Green became embroiled in allegations of fraud and mismanagement.

In 1997, a Howard County judge ordered him to pay back $20,000 to pet owners for grave markers that he never delivered, and for instances when he mixed up cremation ashes, The Sun reported. His office manager testified that Schaefer’s dog, Willie II, had been kicked and stomped before burial. Green denied that claim.

“If I could sell the property, I would,” he told The Sun, “but there’s not a soul who’d want it.”

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

Well, businessman Gunter Tertel did. He bought the cemetery under the name Bonheur Land Co. for $219,000 and continued the business another few years. He announced in 2003 that he was stopping burials. “No funds, no money,” he told The Sun.

Soon, pet owners and volunteers such as Warden formed Rosa Bonheur Society Inc. Pet cemeteries lacked the legal protections of other burial grounds, and now other interests were beginning to come calling.

The land was valuable real estate.

No rest in peace

Ernest Bowen served in the Army during WWII, his grandson said, before he settled with his wife, Annie, in Laurel.

On weekends, the Bowens hosted country dinners for their children and grandchildren with venison and gravy. Ernest hunted the deer. Annie made the famous coleslaw and potato salad. The family’s still making her recipes.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

“She was a redhead, so she was a little fiery,” said Russell Allen, their grandson.

A practical, hardworking man, Ernest Bowen didn’t see the value in spending more for an expensive cemetery. The Bowens were buried side by side near the front of Rosa Bonheur about 30 years ago.

Allen lives nearby and, from time to time, he would visit their graves.

Last December, volunteers found several graves had been disturbed and called WBAL-TV. When Allen saw the news and hurried over, he found his grandparents’ graves unearthed.

“Everything was tore up. A total mess,” he said. “The headstones were just piled up.”

Allen doesn’t know what became of his grandparents’ bodies, but he brought their headstones home for safekeeping.

Later, he met a surveying crew at the cemetery, and the workers told him the bodies had been reburied.

“Supposedly, they’re in the back corner,” Allen said. “They moved them back there, but we have no proof of that. We have no confirmation of that. At this point, I’m not believing anything.”

Read More

His family wasn’t notified that Ernest and Annie’s graves were to be moved, Allen said. The Maryland Office of Cemetery Oversight continues to investigate the matter, a spokeswoman said.

“It’s rather disgusting,” Allen said. “I would like to know where they’re at. I want it proven that it’s them and they’re not just piled up. And I would like to basically ruin whoever is involved.

“You just don’t dig up people’s families.”

A hidden owner

Allen’s question of “whoever is involved” swirls among the volunteers, too. The owners of the cemetery have not identified themselves publicly.

State tax records show that Tertel’s Bonheur Land Co. sold the grounds to a company called Memorial LLC for $100,000 in 2016.

Maryland law generally requires permission from a state’s attorney to dig up a grave, and only for a limited number of reasons.

In August of last year, Owings Mills attorney Larry Caplan wrote the Howard County State’s Attorney’s Office for permission to move nine Rosa Bonheur graves, including those of Ernest and Annie Bowen.

Caplan wrote that he was making the request on behalf of a Naples Asset Recovery LLC. That company is registered to development consultant J. Kemp Deming, of Fort Myers, Florida. His website lists his consulting projects to include the new 250-unit Refinery Apartments beside the cemetery.

“All I did was process paperwork,” Deming said.

He directed questions back to the attorney, but Caplan did not return phone calls or emails. The state’s attorney’s office approved his request to move the graves.

State law also requires a public notice of disinterment. That notice was printed in the Howard County Times on July 6, 2023, and stated the bodies were to be moved to allow for construction on U.S. Route 1 and the other roads around the cemetery.

A state highway spokesman said the cemetery’s owner was exploring development opportunities and engineers submitted plans for roadwork. But who is behind Memorial LLC?

Warden and other members of the Rosa Bonheur Society Inc. believe that Howard County developer Mark Levy owns the cemetery. His companies own land on both sides. A deed shows Memorial LLC transferred a strip of land from the cemetery to one of his companies for $0.

Reached on his cellphone, Levy said he was too busy to talk to a reporter and would call back. He hasn’t.

Meanwhile, worried about more digging at Rosa Bonheur, the volunteers are pushing for legislation during the next General Assembly session to require additional notice to family members before a grave can be moved.

They have taken on the role of the pet cemetery’s watchdogs, monitoring the grounds for disturbed graves or construction crews. Rosa Bonheur is more than a forgotten curiosity to them.

“We need to take a stand,” Zinner said. “Today, they come for your pets. Tomorrow, they come for your bodies.”

Imagine if your final resting place wasn’t final after all.

Comments

Welcome to The Banner's subscriber-only commenting community. Please review our community guidelines.