In a couple years, Maryland schools will teach kids to read using brain science, find struggling readers early, and make individual plans to get them caught up by the end of third grade.

That’s according to the new comprehensive literacy policy approved Tuesday by the Maryland State Board of Education. That policy recommends struggling readers repeat third grade if all else fails.

The policy passed on a 11-1 vote, with two members abstaining. This was the fourth revision of the policy, which board President Joshua Michael said has drawn “some of the most public engagement that we’ve received in recent years.”

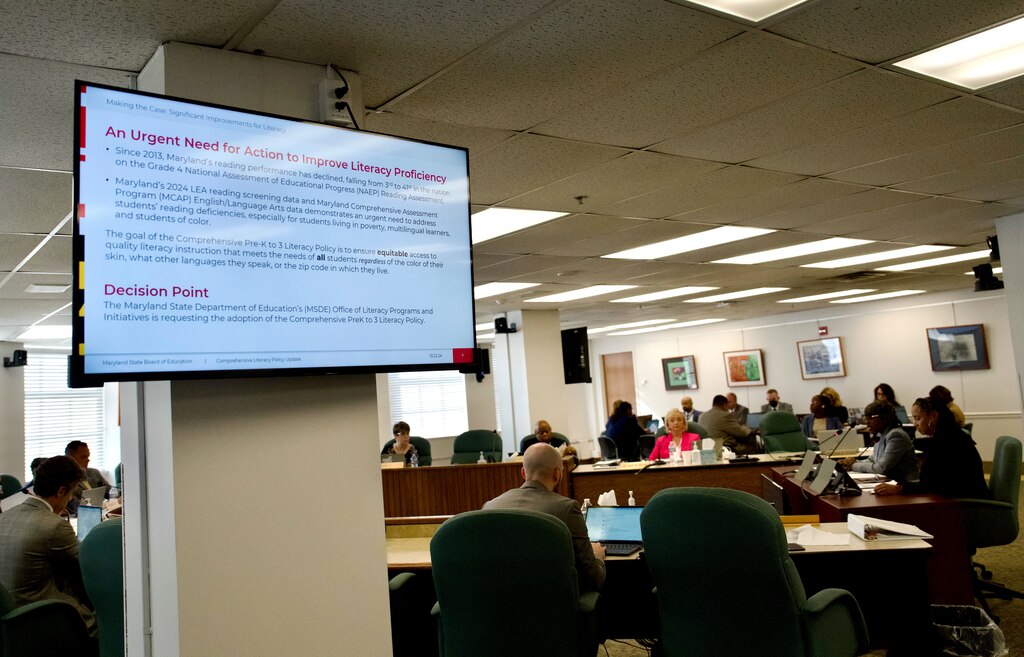

In a presentation, the education department said there’s an “urgent need” to address uneven state test scores, especially among students with social and economic disadvantages.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

“The goal of the Comprehensive Pre-K to 3 Literacy Policy is to ensure equitable access to quality literacy instruction that meets the needs of all students regardless of the color of their skin, what other languages they speak, or the ZIP code in which they live,” the education department said

Here’s what to know about the new policy.

Read More

Parents get the final say

Every student in the state is supposed to be reading at or above grade level by the end of third grade.

To move on to fourth grade, students must demonstrate proficiency on a statewide English assessment. But there are some exemptions, such as for some students with disabilities and individualized education programs, as well as students already held back in a prior grade.

And perhaps the most notable exemption: The policy says third graders can only be held back “with parent/guardian consent.”

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

An earlier draft the policy mirrored one introduced by State Superintendent Carey Wright in Mississippi, which had no such exemption, but the state walked that back in August.

If it’s determined a student should be “retained,” the official word for held back, guardians must be informed, including with an “explanation of the potential risks and benefits of both promotion and retention.” Parents who still choose to promote their children, or send them onto the next grade, must enroll them in a free supplemental reading support program provided by their school district.

If parents don’t provide an answer to their child’s school, the school must keep following up through email, mail, phone calls and even home visits. If there’s still no answer, schools must communicate via certified mail twice in the summer that the student will be held back.

The retention portion of the policy won’t go into effect until the 2027-28 school year, which is a year later than originally proposed.

Schools must find struggling readers early

Starting in the 2026-27 school year, school districts will have to screen students three times a year to help spot struggling readers early. Then they must put students on a personalized reading improvement plan within 30 days, with guardians notified. That includes students who are held back or who go onto fourth grade because of an exemption or parental intervention.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

Wright said the state is going to ensure fourth grade teachers are prepared to take on children who may still be struggling to read.

Michael said that fundamentally, the literacy policy is not just for third graders: It’s meant to capture kids starting in pre-K.

“The answer of whether to promote or retain a third grader is actually neither. It’s to have intervened two or three years before,” Michael said.

Literacy starts in pre-K

The science of reading should start with pre-K, according to the policy — a call that goes hand-in-hand with the state’s ambitious expansion of pre-K spots for all 4-year-olds and low-income 3-year-olds.

The science of reading is instruction that emphasizes phonics — the sounds of letters and how they come together to form words — and how the brain processes written language.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

“We want to make sure that we’re intervening early and catching kids as early as we possibly can,” Wright said. “There’s a whole lot of research around the fact that if you get to them early and then give them the right intervention, that they become very good readers.”

The education department said future expansions of the policy will incorporate more provisions for pre-K students as well as the needs of kids in grades 4-12.

Teachers get trained in the science of reading

All educators in grades pre-K through third should receive training in the science of reading by Sept. 1 of each school year, according to the policy. The state education department will provide that training starting this school year.

Teachers should soon be using state-approved, high-quality instructional materials. Those materials won’t include methods such as three-cueing, which the state says is a “flawed model of teaching children to read.”

To get their license, teachers going into early, elementary and special education will need to pass an assessment that tests their knowledge of the science of reading.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

Not everyone is happy with the policy

Ahead of Tuesday’s meeting, Maryland READS called for the education department to establish a task force that would allow stakeholders to meet with state leaders “to shape the evolving policy.” The organization applauded the department and Wright for responding to feedback and revising the policy, but said the result was “imperfect.”

“Consistent and formal engagement will ensure greater collective collaboration among all stakeholders and MSDE, foster transparency, and provide opportunities to fine-tune the policy and its rollout, maximizing its impact,” Maryland READS said in a statement.

Liz Zogby, an advocate for Maryland students with disabilities, expressed concerns with a provision that states if a student already has reading goals as part of their individualized education program, that student would not receive a reading improvement plan.

Zogby said that is rooted in the belief that an individualized education program is a comprehensive set of interventions that includes everything a student needs to read — but that’s not always true.

“Students with IEPs will easily be excluded if they are not intentionally included,” Zogby said.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

After the policy was adopted, Wright said that it would be duplicative for students to have an additional reading plan.

Xiomara Medina, the one board member to vote against the policy, expressed concern that struggling students could be held back if their parents can’t be reached to make a decision. She said the “default” option will “impact the neediest students.” She wants a clearly defined plan for how districts can increase family engagement.

“I really think that’s going to be less than a handful of parents,” Wright said. “For us, it’s making sure that parents are involved in this decision. That’s the most critical part for us.”

Michael, the board president, who abstained from the vote, said there’s room for evolution of the policy in the future.

“Whatever is passed today is a beginning,” Michael said. “This reflects the initial draft that will be reviewed annually based upon implementation data and public feedback.”

About the Education Hub

This reporting is part of The Banner’s Education Hub, community-funded journalism that provides parents with resources they need to make decisions about how their children learn. Read more.

Comments

Welcome to The Banner's subscriber-only commenting community. Please review our community guidelines.