Sonja Brookins Santelises plugged gospel music into her earphones and started praying as she headed down from her fourth-floor North Avenue office to confront a large irate crowd awaiting her at a school board meeting.

The heating systems had failed at 60 Baltimore city public schools that ice-cold week in 2018, leaving some students shivering in 40-degree classrooms before schools were shut down. The scene drew national ridicule and stinging words from the governor, who called it a “horrendous crisis.”

As parents began shouting and the crowd grew unruly, the school board chair threatened to adjourn the meeting. When it was her turn to speak, Santelises took responsibility and outlined actions she would take to address longstanding heating-system problems. Then, speaking with a pastor’s fervor, she asked the crowd for help in her effort to fight state policies that she estimated had cost the system $66 million in state money for building repairs.

Hostility faded into applause.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

That moment, 18 months into Santelises’ tenure as Baltimore City Public Schools CEO, offered a glimpse at how she would lead the school system: confront problems head on, present well-researched solutions and seek to change what many view as a racist narrative that school leaders are incompetent and Baltimore’s Black children can’t learn.

2020-21 By The Numbers

Enrollment: 77,807

Number of schools: 155

Four-year graduation rate: 69%

Source: Baltimore City Schools

Interviews with more than two dozen people paint a portrait of an effective administrator who listens, makes connections in the community and has pushed for academic gains. She doesn’t seek attention, but she is known for her sharp mind and her ability to motivate a crowd. A school system that once bounced from crisis to crisis is viewed as largely scandal-free and showing evidence of steady leadership.

There are “five great superintendents in the country. She is one of them,” said Bob Hughes, the Gates Foundation director of K-12 education, who has awarded grants of $24 million to the city schools since 2016. “She is that strong. She really is a visionary.”

While she has won over many critics since taking the helm of the district six years ago, others see the 54-year-old educator as a flawed leader. They contend that she didn’t respond adequately to an investigation into questionable high school grading changes and may have pushed too soon to bring students back into schools amid the COVID pandemic.

There is also consensus that too many students aren’t getting the education they deserve, a view confirmed by a Baltimore Banner poll of city residents showing that a majority view the city schools and Santelises unfavorably. Roughly one in five students passed state exams in 2019, about half the state average. Chronic absenteeism is high, enrollment continues to drop and graduation rates remain below the state average. Despite about $1 billion spent to renovate and rebuild schools in the past decade, many still are not adequate.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

Thomas Eppes, 54, a Northeast Baltimore resident whose son is headed to Baltimore Polytechnic Institute in the fall, gives satisfactory grades to Santelises but believes more can be done to improve a school system that faced an array of systemic problems when she arrived. “I believe her job is to fix it. And to fix it quick. You know, I think she’s doing all right, but I mean, she can do a whole lot better.”

Among her sharpest critics is Gov. Larry Hogan, who along with other Republicans has focused on a Maryland Office of Inspector General report that revealed some teachers and school administrators had changed high school grades between 2016 and 2019. While some believe the report turned up little, Hogan last week referred the matter to the state prosecutor, saying that “there has been a clear moral failing by school administrators who appear more concerned with their own image than with the well-being of their students.” Then GOP legislators wrote to the state superintendent requesting an audit and calling for Santelises to resign.

Backers, however, note that the system was showing progress academically before the pandemic and that Santelises’ skills and nearly decade of experience in the district make her the right person to help realize further gains and bring improvement to dozens of schools. The coming year is a critical time, with the system poised to receive an unprecedented boost in state and federal funding come July 1. Baltimore has been waiting for such a moment since 1997, when the state legislature intervened and tried to put the system on a different path.

But will Santelises opt to stay in a demanding job that requires withstanding a torrent of criticism and where educators don’t typically remain for extended periods?

She is already poised to become the longest-serving school leader that Baltimore has seen in some three decades. Five police chiefs and four mayors have come and gone since Santelises started in July 2016. She earns $339,000 a year.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

“The idea that we have had stability for six years is a big deal,” said Peter Kannam, who served on the school board that chose Santelises and is now the principal of Henderson Hopkins, an East Baltimore elementary/middle school. Since she arrived, he said, “more students are showing up every day and getting cared for. They are getting taught more challenging material. The resources that are coming in are significant.”

Sounding like a pastor again, Santelises said she is determined to get the system back on track and has no plans to seek a superintendent’s job elsewhere. But she has told the board that she will leave when she is called to do so.

“I cannot leave before God tells me I can leave and once he tells me to leave there is nothing you can do to keep me,” she said.

Deep ties to Baltimore

Santelises came to Baltimore from Boston, where she grew up and later worked as an assistant superintendent for the Boston Public Schools. One of her roles there was leading a network of 23 “pilot schools” that had broad authority to meet the needs of low-income students and improve their achievement.

A graduate of Brown University, Santelises holds a master’s degree in education administration from Columbia University and a doctorate in administration, planning, and social policy from Harvard University. She first came to Baltimore City Public Schools in 2010, serving as the chief academic officer to then-CEO Andrés Alonso. She left in 2013 to become vice president for K-12 policy at The Education Trust, a liberal-leaning think tank that focuses on closing the achievement gap for low-income students of color.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

After three years of commuting to Washington, D.C., for that job, she returned to the Baltimore school system in July 2016, seeking to build on some of the work that she and Alonso had started.

By that time she and her husband had three children in the city’s public schools, offering her two perspectives on what was working and not working in the system. (Only one of those children will remain in city schools this coming school year. The other two will attend a private girls school.)

Santelises kept a low profile at first, but then a financial audit that she had ordered revealed a $129 million structural budget gap for the coming year. She said she was advised to keep the shortfall under wraps, but instead she went public. About half of the gap was the result of commitments that her predecessors had made to renovate buildings and pay teachers more. After state officials helped fill half the gap, Santelises was forced to cut deeply to make up the rest. She laid off about 300 employees.

With limited financial resources, she decided to focus investments on three areas: improving literacy, curriculum and what she called student wholeness.

Recent CEOs had not given as much attention to what was happening inside classrooms, but she zeroed in on lessons. Teachers and principals said she focused on providing students with better reading instruction and a more balanced array of classes that was rich in the arts, sciences and social studies. Many of these subjects had been dropped or sidelined during a period when urban schools doubled down on tested subjects, math and reading.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

Santelises also mandated that teachers use a nationally recognized curriculum, Wit and Wisdom for reading and Eureka for math. For the first time in years, a student who moved from East Baltimore to West Baltimore during the school year was learning from the same textbook.

Her love of analyzing instruction has led her to make frequent surprise visits to schools to see what is happening in the classroom, when no special lesson has been prepared. Principals say she’ll talk to teachers and the principal about what she is seeing.

In the first week of the current school year, she visited Chris Battaglia, the principal of Benjamin Franklin High School, and asked staff members about their concerns. “She is extremely intelligent without being above you. … With so much responsibility, with so many people coming at her, she always has the ability to make you feel she is in it with you. There are some things that drive me crazy, but I always believe she has the kids in the forefront,” Battaglia said.

That singular approach appeared to pay benefits right away. When the spring 2018 test results were released, city elementary and middle school students showed percentage-point gains that were twice the state average, outpacing many higher-performing county school systems.

While Santelises declared at the time she wasn’t “throwing a party” because only one in five students was passing the tests, she said there was cause for optimism. It was the first time in nearly a decade that the city schools had shown significant test-score gains. The school system saw smaller academic gains the following year, but it was still making progress.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

Then the pandemic hit.

Santelises threw herself into managing the crisis, but she was personally disappointed that the system had lost a chance to show that nearly a third of the schools were making substantial academic gains.

“We were on an upswing, and I think that we lost the momentum. Everyone has adverse effects from the pandemic,” said Ben Mosley, principal of Glenmount Elementary/Middle school. He is among those who counts Santelises as the city’s strongest leader.

As schools closed their doors, Santelises grew uneasy almost immediately that so many students for whom school was a stabilizing force were left without access to an education, said Johnnette Richardson, the school board’s chair. Many students lacked computers and internet access, had to go without daily breakfasts and lunches, and weren’t able to interact in person with important teachers and school staff.

While the city poured energy into finding laptops and hotspots and extending Wi-Fi, Santelises clashed with the Baltimore Teachers Union, which issued a list of non-negotiable items that it wanted to see in place before educators returned to work.

Santelises held firm and began opening schools in September 2020 to small numbers of the most vulnerable children, relying on teachers and aides who had volunteered to return. Knowing some families were reluctant to return, the school system set up an extensive COVID-19 testing program that required once-a-week tests for unvaccinated staff and students with a signed permission slip. The testing plan kept the incidence of spread in the city schools to some of the lowest among the state’s school systems.

The BTU was critical of the decision to reopen schools before other districts, saying it didn’t believe the system had taken enough steps to keep children and staff safe. In the end, teachers returned to work, but Santelises recognized they were exhausted and approved more time off and a raise in pay.

Last January, as the omicron variant raged and winter break was ending, the BTU and several City Council members asked Santelises to delay the return to school for a few days until COVID testing was complete. Santelises held a news conference with a half-dozen elected leaders and said she would not do so. BTU President Diamonte Brown called the decision a “fundamental failure.” (Brown declined comment for this story).

In the days that followed, so many students tested positive that school leaders struggled to juggle staff and student quarantines. Families weren’t notified of positive test results until the following Sunday, when they had to scramble to get child care. Santelises publicly apologized. She said the inability to send out notices earlier had had an impact on staff, school leaders and families.

“I am truly sorry,” she said. “I resolve to do better.”

While annoyed by the failure at North Avenue to make quick decisions, school leaders found the apology refreshing. She hadn’t blamed them.

Banner poll reflects dissatisfaction with BCPS, Santelises

While Santelises is well-respected nationally and within the district, she has her critics — and the prevailing public view of the school system seems to be one of deep cynicism. Only 26% of residents approve or strongly approve of the job that Santelises is doing, according to a new Baltimore Banner survey conducted by the Goucher College Poll. And 84% of respondents said students not meeting academic standards is a major problem for the city schools.

The notion that Baltimore city schools are failing their students has been amplified in recent years by Fox 45, a conservative-leaning news outlet. The station has run numerous stories asking city leaders whether Santelises should resign. In some cases, the reporting did not provide context for statistics or complaints by parents.

“It is profound. It affects the way our families see their schools. It affects the way students see themselves,” said Alison Perkins-Cohen, the system’s chief of staff. “It is around you all the time. It is a barrage.”

Santelises acknowledged that improvement is needed, but she said the “blitzkrieg” of negative news coverage has been “deliberative” and plays to a narrative that suggests Black children can’t learn. “It is very strategic and it is out of an old playbook. … And it is a playbook that is working now,” she said.

She also weathered criticism in 2020 after an internal school investigation found that administrators at Augusta Fells Savage High School had schemed to inflate enrollment, pressured teachers to change grades and scheduled students in classes that didn’t exist. The principal was replaced, and other personnel changes were made.

Then last week, an inspector general found extensive grade changing in high schools from a “misunderstanding and misapplication” of policies detailing how grades can be legitimately changed, particularly before a new grading policy in 2019. The city schools have said that the incidents in the report “largely occurred before the policy change in 2019 and did not illustrate systemwide pressure to change grades.”

That controversy is what prompted some Republican legislators to call on Santelises to resign.

"I cannot leave before God tells me I can leave and once he tells me to leave there is nothing you can do to keep me.”

Sonja Santelises

Individual teachers have a varied view of Santelises.

Elainia Ross-Jones, a statistics and probability teacher at City Neighbors High School, is angered by Santelises‘ insistence on a new evaluation system that teachers believe is onerous. She said that there have been positive changes but that academic initiatives haven’t been as successful as the CEO had hoped.

“I think she has tried to focus hard on community engagement and raising academic standards,” Ross-Jones said. “I don’t think it has worked the way she thinks. As many before her, the initiatives start and stop and they don’t go through. ...There hasn’t been a lot of transparency.”

But Jamilla Fort, a Cecil Elementary School math teacher, said she has been allowed to try new methods in her classroom and believes they have helped bolster achievement. “We saw tremendous growth in student achievement since she has been here,” she said, describing Santelises as “super smart” and an innovator.

Even when teachers “roll their eyes about North Avenue it is not about her. … I have never heard her badmouthed even casually. … She is better than your average superintendent by a long shot,” said Alex Funk, a Patterson High School math teacher.

During the intense debates over whether schools should stay closed during the pandemic, Santelises sought to understand the fears and concerns of parents and others in neighborhoods she might ordinarily not hear from.

One of them was Akil Trice, who had started The Movement Team, a community organization. “She wanted to go and hear the voice of the community,” Trice said.

Trice took her out three times to tour different areas: a barbershop in Reisterstown Plaza, the Greenmount Recreation Center, a church in Brooklyn, a family in Upton and a boxing gym.

“We never had a school superintendent come inside the barbershop and inside our church and ask what can she do,” Trice said. “They walked away looking at her differently. She didn’t make excuses. …They were impressed.”

Santelises continues to check in with those on-the-ground sources, calling on them to provide the kind of honest feedback that she needs to understand the impact of policy decisions on students.

She has also gotten support from activists at crucial times.

Santelises had chosen a principal for a school in Cherry Hill that some community leaders were unsure about. Forces were aligning against her pick until Kin “Termite” Brown-Lane, a longtime Cherry Hill resident, invited the principal candidate to a football game where he met a lot of parents. The invitation turned the tide.

“We are concerned and nobody wants to hear the little people. She made it her business to talk to people in the community,” she said.

On the day the community gave out Thanksgiving meals, Santelises showed up to help serve. And when a 23-year-old relative of Brown-Lane was murdered last February, Santelises went to the funeral home. “She has been a complete blessing in my life since I have met her. Anything I see in the schools in Cherry Hill, I will call her,” Brown-Lane said.

Trying to turn the tide

As Santelises began focusing on how schools were going to come back from the pandemic, she decided teachers and staff should focus first on reestablishing relationships with students, some of whom had suffered alienation during the pandemic.

The administration decided to spend federal dollars on an expanded summer school, intensive tutoring and ways for high school students to pick up courses they had failed or hadn’t gotten to take during the interruption of the pandemic.

Santelises relies heavily on her cabinet, a dozen or so high-level administrators in charge of everything from technology to finances to academics. Most started their jobs after Santelises arrived, and observers say some of the strength of the system lies in the competence they see at this level.

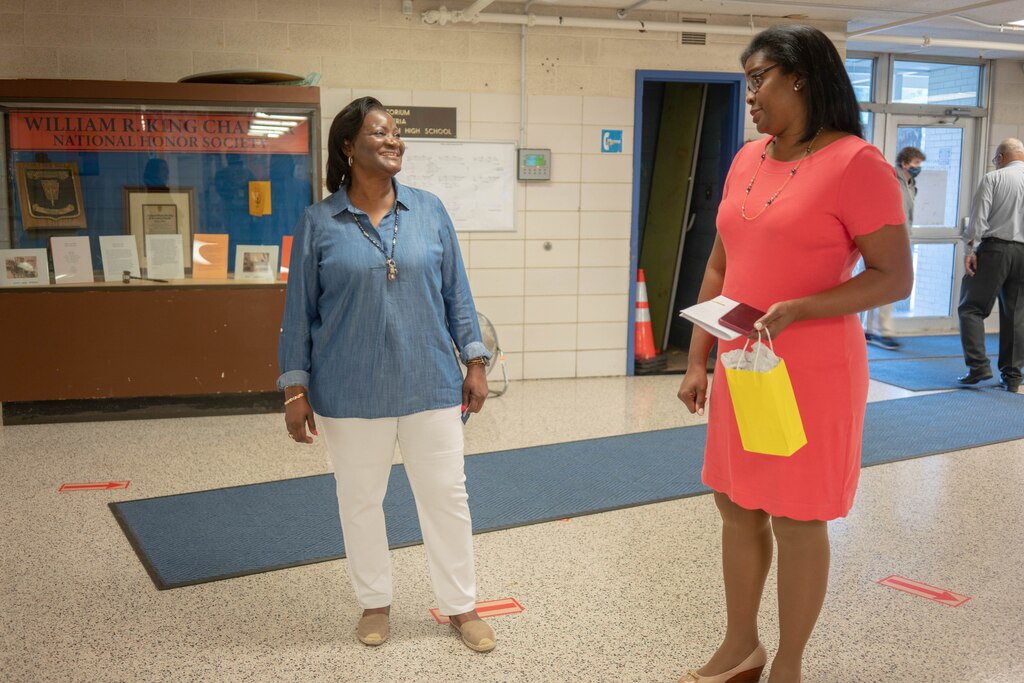

But she does not shy away from decisions, said her aide, Perkins-Cohen. And she often gives principals clear directions. On a recent Teacher Appreciation Week stop at Baltimore Polytechnic High School, she spoke with Principal Jacqueline Williams about students whose college acceptances included Ivy League universities. Santelises had told Williams several years ago that the school — considered one of the best in the city — wasn’t getting enough of its students admitted to top-tier colleges. That has changed, she said. Santelises also has nearly doubled the number of middle school students taking Algebra I, considered an important gateway course to college.

Maryland State School Superintendent Mohammed Choudhury said he is impressed with the work in Baltimore city schools on improving teaching.

“She is super-sharp from the academic and research base of teaching and learning,” Choudhury said.

But he said he would like to see Santelises focus more on schools that have been low-performing for years. “You do have to be very aggressive and focused on your low-performing schools, something I haven’t fully seen yet,” Choudhury said.

Santelises’ chance to turn around the Baltimore City Public Schools comes as the district receives an unprecedented infusion of federal and state dollars. This includes $689 million in federal pandemic funding over several years, on top of money provided through a once-in-a-generation state investment in education called the Blueprint for Maryland’s Future. The $1.6 billion budget that goes into effect on July 1 will have $230 million more than last year’s, a 16 percent increase. Most of that state money will go directly to principals to spend on a list of systemwide academic goals.

Hampstead Hill Academy Principal Matt Hornbeck is optimistic that city schools can become more than just hubs of learning, but also places that people see as the center of their community.

“It is a time of amazing investments in public education. It is a time of great hope and enthusiasm,” Hornbeck said.

When the pandemic shut down schools, Santelises joked, she may have been one of the few superintendents in the state who was saddened to see testing suspended. The results from testing this past spring will offer the first in-depth look at where students stand after the pandemic. While she doesn’t expect students to get back to where they were in March 2020, she does expect to see progress. Some internal midyear assessments show gains, although she declined to share the numbers until the end of the year.

State Del. Maggie McIntosh is among those trying to persuade Santelises to sign up for another four years after her current contract expires in June 2024.

“She is very strong, professional, confident and yet when needed a fierce advocate for our kids. She is well-respected here” in the legislature, the Baltimore Democrat said.

Few superintendents stay in their jobs for more than eight years, although statistics show that districts with stable leadership make the most progress.

Santelises said she won’t depart before schools and students have moved past the pandemic and started to show signs of sustained progress. Santelises hopes city parents will soon see many more schools headed in the right direction with strong principals and good teachers, even before there is a leap in test scores.

“I want this community to be prouder of their schools than they are. And I want them to see an upward trajectory,” she said. “Not that they are going to be perfect. Not that we will achieve everything. I think Baltimore families deserve that and are owed that.”

liz.bowie@thebaltimorebanner.com

Read more: Baltimore city residents are frustrated with the state of schools, poll finds

Comments

Welcome to The Banner's subscriber-only commenting community. Please review our community guidelines.