We are fools for Christ’s sake.

So believed the apostle Paul when he penned a letter to the Corinthian church. And so, too, believed Maryland’s pioneering clown ministry.

This niche style of Christian outreach is as outrageous as it is earnest, and traces some of its roots back to Columbia. It’s perhaps a legacy that James Rouse never imagined when he founded the Howard County town, with its distinctive urban plan, efficient use of land and commitment to diversity. Rouse included a series of interfaith centers intended to bring people of different beliefs under one roof. The model inspired one local pastor at Abiding Savior Lutheran Church to pursue his own experiment blending liturgy with laughter.

These days, Rev. Floyd Shaffer is remembered by some as the “clown father” of modern Christian clowning. Though liturgical clowning already had a history in Europe, Shaffer spent his time in Columbia in the 1970s dabbling in clown ministry and eventually became known as a leader of the movement in the United States. He died three years ago, his wife Marlene Shaffer confirmed.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

Even though the whimsical ministry’s heyday was in the 1980s and ’90s, some Christians continue to answer the call to clown. And the practice has captivated new audiences on TikTok and YouTube.

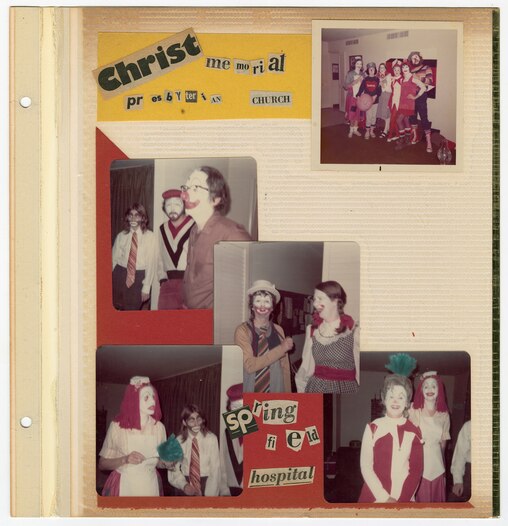

Earlier this year, the Columbia Maryland Archives put together an online exhibit about the town’s nondenominational clown ministry, called Faith and Fantasy, which Shaffer founded in 1974. Archivist Erin Berry said staffers were inspired after stumbling across a popular YouTube channel’s episode on Christian clowning.

Shaffer’s idea for a clown ministry came to him in 1964 on a beach in Fort Lauderdale, Florida. The pastor was in town for a Bible study and leafing through some books when he stumbled across the etymology of the word clown. He connected it with Jesus’ command to be a servant.

That same year, Lutheran church leaders were getting creative with clowns — and it wasn’t going over well.

The National Lutheran Council produced the short film “Parable,” which depicted Jesus as a white-faced clown and the world as a circus.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

The film’s 1964 debut at the New York World’s Fair roiled event organizers, some of whom resigned in protest. One “disgruntled minister threatened to riddle the screen with shotgun holes if the film was shown,” the Library of Congress noted when it announced that it had selected “Parable” for preservation in the National Film Registry in 2012.

Six years later, Shaffer debuted as a clown minister for the opening day of Abiding Savior’s vacation Bible school, according to a news article preserved in Columbia’s archives.

“I don’t think that something that’s so controversial — I don’t know what other word to use — as clowning ministry could flourish in another place other than Columbia,” Berry said. “You could just try what you wanted to try.”

Other leaders within Columbia’s interfaith centers encouraged Shaffer to keep at it, said 86-year-old Marge Goethe. Her husband, Rev. Jerry Goethe, the pastor for Kittamaqundi Community Church, suggested to Shaffer that he teach a class on clown ministry. Together, the two men designed a seven-week course that covered theology, the history of clowning, skits and games to encourage playfulness.

Many local residents, including Marge Goethe, enrolled in the classes, embraced clown ministry and set out to visit children’s hospitals, retirement homes and domestic violence shelters. She learned how to silently deliver sermons with gestures and humor, but never mockery. Goethe used lipstick to draw a red circle — a symbol of the liturgical clown — on her cheek.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

Goethe developed her clown persona and named him Harry, after a man she knew as a child who lived on the streets. He was a reminder that she could either be the kind of person who brushed him off or helped him out.

Howard County’s clown ministry eventually grew to include as many as 300 clowns, The Baltimore Sun reported in 1994. Members of the Faith and Fantasy ministry went on to teach clown ministry around the country and internationally.

Not every audience loved the routine.

During a worship service at a Virginia college’s youth convention, Goethe and other clown ministers offered to draw the mark of the clown on people’s cheeks.

“What is that, the mark of the devil?” one man asked.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

Goethe couldn’t reply while she was in character.

“All I had to do was accept what he was feeling at the time and hope it changed at some point,” Goethe said.

Goethe still attends Kittamaqundi services and performs clown ministry. When people ask her about the decades she spent cheering up strangers, she worries she won’t find the right words to explain how rich clown ministry turned out to be.

“I did more good for people being silent,” Goethe said.

Shaffer eventually moved to Ohio and authored several books with titles such as “If I Were A Clown” and “Clown Ministry.” He produced instructional videos on clown ministry that lately have found a rapt audience on the internet.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

Jen Bryant realized she had a personal connection with clown ministry while putting together an episode on the subject for her YouTube channel, Fundie Fridays, which features cultural commentary on aspects of fundamentalist Christianity in the United States. The Missouri resident’s grandfather, a Catholic, performed for a time as a clown minister under the name “George-o.”

Every community seems to have its subcultures, Bryant said, and she found that was also true for clowns. There are classical clowns like Joseph Grimaldi, a Regency-era entertainer who introduced the white face makeup. There are dark clowns like Juggalos, a nickname for fans of the hip-hop group Insane Clown Posse. And there are scary clowns like Pennywise, the shapeshifting antagonist in Stephen King’s 1986 horror novel “It.”

At first, Christian clowns sounded like a meme to Bryant. The full story, she said, turned out to be “way more interesting.”

Bryant and her husband James Bryant ordered copies of Shaffer’s books and collected a variety of research on clown ministry for their episode, which posted in April. The hourlong segment earned an “overwhelmingly positive” response from their audience, many of whom are in the midst of deconstructing their faith and understanding of Christianity, Bryant said.

“Everyone just thought this was just the most pleasant little novelty,” James Bryant said.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

Maybe Christian clowns are even the original deconstructors.

“They’re people who went, ‘faith wasn’t working exactly how we wanted it to, so we broke it down and changed it,’” he said. “It worked. It has a legacy.”

Appearing in a video on Kittamaqundi’s YouTube page, Shaffer said clown ministry gives people a new way to live out and enjoy theology, “instead of being so glum and gloomy and solemn, as much of the church has become.”

Many Bible stories defy rational thought and that’s sort of the point, Floyd said in the video.

Scripture, Floyd noted, often suggests that God has a sense of humor.

Comments

Welcome to The Banner's subscriber-only commenting community. Please review our community guidelines.