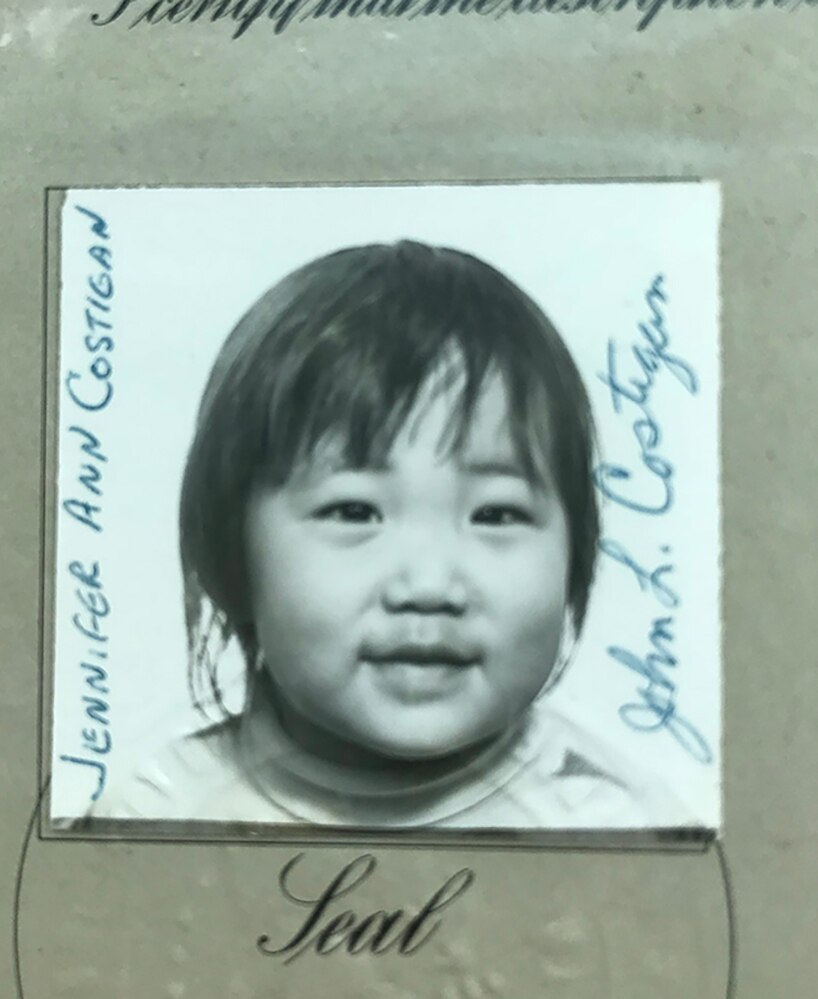

The day after the presidential election, Jennifer Evans went to a local office supply store and bought binders. She said she knew she needed to protect herself.

The Towson resident said she made copies of her adoption papers and naturalization documents. Evans tucked them into those binders, with one more copy placed in a locked safe and another in her purse. She also has photos of those documents saved in her cellphone.

The extensive measures were prompted, she said, by a primal fear Evans, 47, carries as a child adopted from South Korea nearly 50 years ago. She arrived in the United States at 3 months old and grew up in southern New Jersey as a citizen, but now she has growing angst about what the return of President Donald Trump could mean for her future.

The prospect of another Trump presidency is producing a newfound level of uncertainty for some international adoptees about whether they will be protected as United States citizens, given Trump’s past comments about immigration, birthright citizenship and China.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

Because Evans was born in another country, she worries she could get caught up in Trump’s vow of a historic mass deportation of undocumented immigrants despite the fact that she is not one of them.

“I hate all this [stuff] people have to do to protect themselves,” she said. “Next is making sure my kids have photos as well.”

An estimated 5 million adopted people live in the United States. Thousands are likely intercountry adoptions, or those adopted from overseas. But experts say it’s impossible to pinpoint an exact figure. Many adoptions are privately arranged and not always recorded by the government. In Maryland, there were 1,133 adoptions, but only 45 from outside of the country, in 2023, according to the National Council for Adoption.

Christopher von Claparede, 25, a resident of the Barclay neighborhood of Baltimore who was adopted at about 18 months old from Kazakhstan and raised in central Michigan, said he is concerned for his fellow intercountry adoptees.

“I have been surprised at some of the stories I have seen recently about adoptees who — because of various situations — have seen their citizenship status challenged, due to previous gaps in the law. And so I wouldn’t be surprised if this became more commonplace or further challenged,” he said.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

Adoptee advocate Alice Stephens and her network of fellow adoptees — particularly those of Asian descent — say fear and anxiety about their legal status are legitimate concerns.

“People are very nervous about it. Not everybody was naturalized when they were brought into this country,” explained Stephens, a 57-year-old Silver Spring resident who authored the 2018 book “Famous Adopted People.”

Stephens, who was adopted from South Korea as a toddler and naturalized a few years later, has multiple copies of documentation proving her American citizenship.

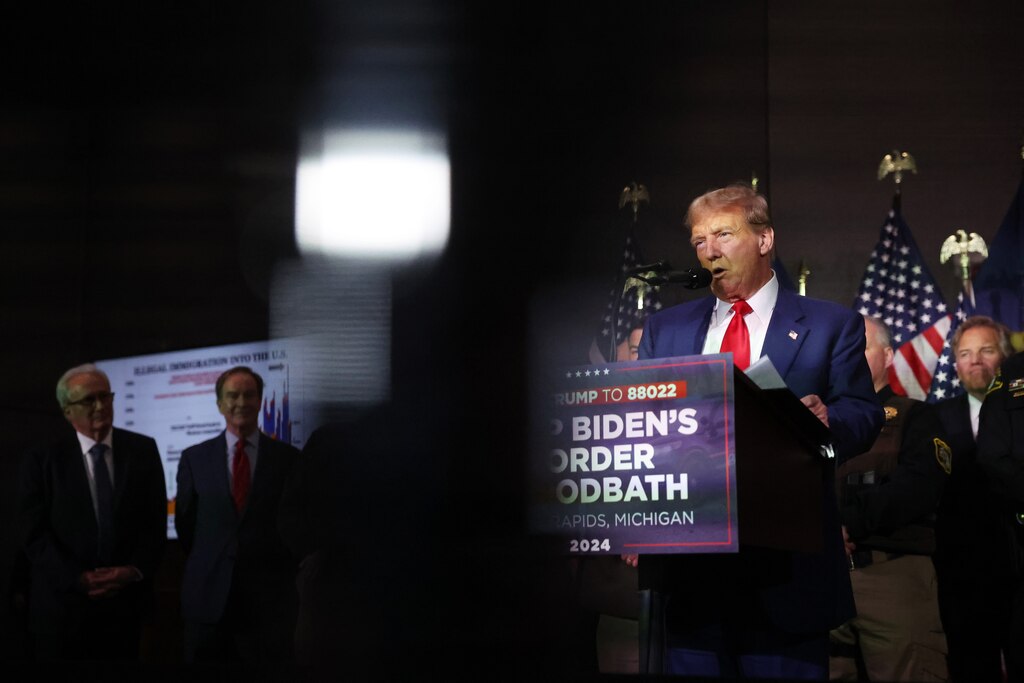

Trump made cracking down on illegal immigration as well as curbing legal immigration major issues throughout his campaign. He has continued making those promises since his election victory.

In November, he said he would declare a national emergency to carry out his campaign promise of mass deportations of undocumented immigrants. A month later, in an interview with NBC’s Kristen Welker on “Meet the Press,” Trump stood by his promise to end birthright citizenship, which occurs when people born in the U.S. automatically become citizens.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

Trump also said he wanted to “work something out” with Democrats in reference to Dreamers — undocumented children who immigrated to the United States with their families at a young age and grew up in this country.

As an adoptee of Asian descent, Evans said, she feels the pressure of anti-Asian, anti-immigrant sentiments, which she feels have been amplified in the Trump era.

“As I grew older and more aware, the stigma around the Korean War, Vietnam War, the China virus — anything Asian and perceived as negative, never really allowed me to identify as Korean or Korean American,” she said, explaining that people conflate being of Chinese descent with all Asians. “I was always labeled by assumption off my appearance. I feel it every day in Baltimore.”

Some people who were adopted legally from another country may, in fact, not be U.S. citizens.

An AP investigation last year found that thousands of children adopted by Americans are without citizenship. Many of them are from South Korea, which has the world’s longest and largest international adoption program.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

The Child Citizenship Act of 2000 tried to help by eliminating the need for many families to apply to naturalize their newly adopted children. But the federal law applies only to future adoptees under the age of 18.

“I was lucky because my parents had access to knowledge and wealth. They knew to get me naturalized and had the ability to traverse all that paperwork,” Evans said.

Adoption advocates say they remember the last time Trump was in office and the anti-Asian hate many in that community felt during COVID-19. Stephens, the author, called that period a “wakeup call” for transracial adoptees because of all the “racism and heightened hate.”

Stephens said she believe she is less likely to be “swept up in an immigration sweep” living in the Washington suburbs. She greatly worries, however, about people living in more politically conservative states who will be in greater danger of harassment and potential expulsion.

“I believe there will be people who will be wrongly deported,” she said.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

Von Claparede said he feels “cautiously optimistic that things will be OK” but understands some of his fellow intercountry adoptees are more concerned.

“I think everyone is cautiously aware of the uncertainty about the citizenship question,” said von Claparede, who helped form the Adopted and Fostered Students Association while in college.

Ryan Hanlon, president and CEO of the National Council for Adoption, said, “if someone is a citizen, I would not encourage them to feel angst. They should enjoy their rights as a citizen.”

Hanlon, who is white and the father of an adopted Chinese child, added that “it is not something that could be changed by a president or an administration.

“I remain concerned for older adoptees who have not received citizenship. I’m not concerned about my son who was born in another country,” Hanlon said.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

Stephens, who was born in Korea, recommends adoptees double-check their citizenship status, make duplicates of related documentation and keep them in a safe space.

“If they don’t have that documentation, find out why,” she said, adding that people should connect with advocacy groups such as Adoptees United and Adoptees for Justice. “Get started now.”

Comments

Welcome to The Banner's subscriber-only commenting community. Please review our community guidelines.