David Schweizer spent New Year’s Day the same way every year: At his loft in New York City, surrounded by friends, sipping vodka, carving a ham and offering up his signature deviled eggs. All while decked out head to toe in leopard print.

This was Schweizer’s famous annual party, where his theater colleagues and other creatives — including Caleb Wertenbaker, his partner of 15 years — filled his New York home with gossip and cheer. “It’s like he waved a magic wand and everybody showed up,” said longtime friend Julian Fleisher.

The parties were always a production, but what else could you expect from an acclaimed director? In his personal and professional life, Schweizer just knew how to bring people together.

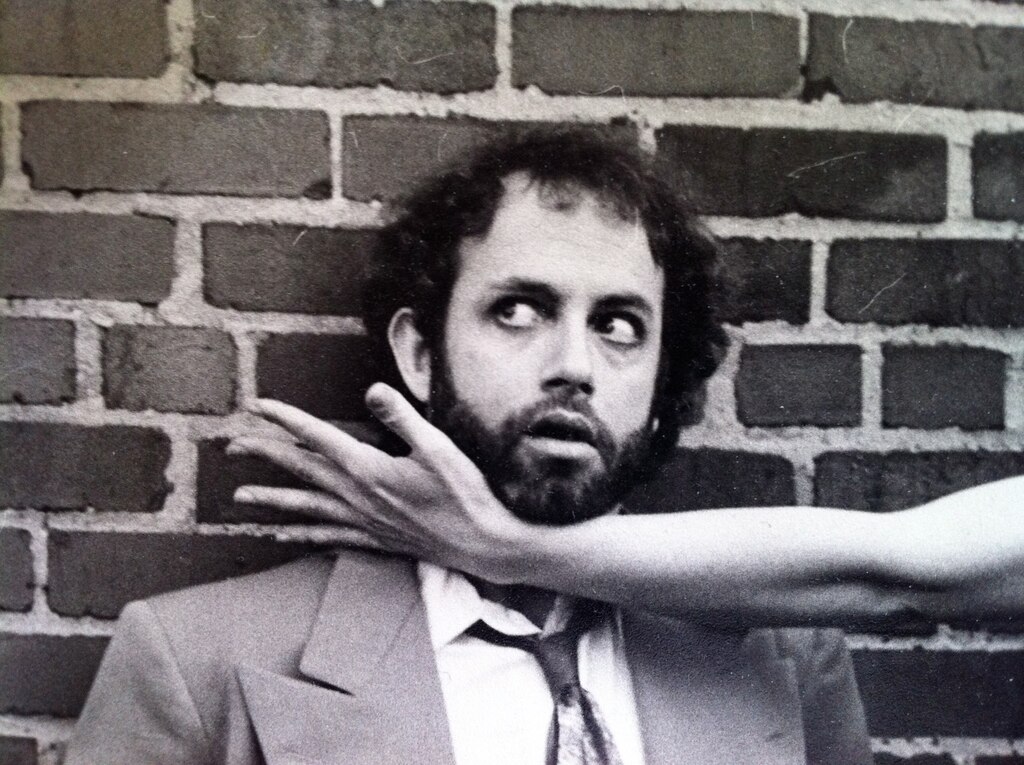

Schweizer’s friends, family and vast theater community are now coming together again to mourn him. Schweizer, a Maryland native who directed shows at Baltimore Center Stage and in Los Angeles and New York throughout his career, died on Dec. 5 of a heart attack. He was 74.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

“There was something cinematic about him,” Fleisher said. “He was a giant from another era — an analog era when people read books and read plays with energy and a passion and a zest that feels like it’s fading. He just showed up for it.”

Schweizer, who is survived by brother Thomas “Tim” Schweizer, was born in 1950 and grew up in Baltimore. He found romance in theater from a young age. At 13, he convinced his parents to let him travel to New York City alone to see Broadway shows, friends said. He attended The Gilman School and later Yale University, where his collaborators and classmates included Meryl Streep, Sigourney Weaver and Christopher Durang.

In his youth, Schweizer also befriended the playwright Tennessee Williams, who brought him to Europe. The two traveled through Italy together.

Schweizer made his New York debut in 1974, directing a reimagined version of Shakespeare’s “Troilus and Cressida” at Lincoln Center. The production starred Christopher Walken, just years before his breakout roles in film.

He went on to direct hundreds of theater and opera productions both across the country and the globe, including some original work. He won an Obie Award, an annual honor given to artists involved in off-Broadway plays, in 2000 for his production of Rinde Eckert’s “And God Created Great Whales” — also the piece that brought his work back to his hometown in 2002 when Center Stage booked the show.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

In total, Schweizer directed more than a dozen shows at Center Stage. Some of them were especially notable. His 2008 direction of “These Shining Lives” by Melanie Marnich was the play’s world premiere. He also directed the Baltimore premiere of “Caroline, Or Change” the same year.

Other Baltimore productions included “The Boys from Syracuse” in 2006, “Snow Falling on Cedars” in 2011, “Bus Stop” in 2012 and “Next to Normal” in 2014.

Fleisher and Schweizer often bonded over their Maryland roots.

“What David and I shared about Baltimore was what all Baltimoreans share about Baltimore, which is just a whole world of ideas in one word,” Fleisher said. “We’d look across the table at each other at a party or at a dinner and just say, ‘Baltimore,’ and we would know exactly what we meant.”

It’s those small chats with his friend that Fleisher misses the most. He was a wonderful conversationalist — “a listener and a sharer, a wise man and a joker,” Fleisher said. He was well-read and intellectual but made every interaction engaging and theatrical. It was like there was always music playing when Schweizer walked in a room, Fleisher said.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

“He considered it part of one’s obligation to the universe to know as much as you can,” he said. “And he was particularly interested in misfits and weirdos and outcasts and artists and queer people.”

Greg Mehrten first met Schweizer at a party in 1976 through mutual friends. Mehrten thought he was “glamorous,” and they quickly developed a strong friendship and professional relationship.

Schweizer had a special ability to spot talent and work well with actors. Schweizer’s work crossed genres and styles, and he’d always find the most interesting collaborators, Mehrten said.

He was also generous with his time and resources, mentoring playwrights and directors who looked to him for guidance, friends said.

“He didn’t just tell people what to do,” he said. “He wanted to create new things with everyone.”

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

It’s hard to pin down Schweizer’s favorite production, Mehrten said. He rarely talked about the past, instead excited by whatever was coming up next. He was working on new projects until the day that he died, his friend said.

Outside of his work, Schweizer was a dependable and funny friend who enjoyed pushing boundaries where he could. Schweizer loved to laugh, and he was always up for a spontaneous adventure, Mehrten said.

At one of his famous parties, the evening entertainment was a lineup of cabaret singers. About five people in, Schweizer turned to Mehrten and said, “I’ve got to shake things up.”

Though he wasn’t a particularly good singer, Schweizer got up and did his own drunken rendition of “The Man That Got Away.” The room was a bit shocked, some unsure how to react and others complimenting Schweizer’s impromptu performance, Mehrten said — “and then he turned to me and giggled and was so thrilled that he had upset the applecart.”

The Banner publishes news stories about people who have recently died in Maryland. If your loved one has passed and you would like to inquire about an obituary, please contact obituary@thebaltimorebanner.com. If you are interested in placing a paid death notice, please contact groupsales@thebaltimorebanner.com or visit this website.

Comments

Welcome to The Banner's subscriber-only commenting community. Please review our community guidelines.