Douglas DeLeaver was many things: an Army veteran, a state trooper, a public servant, the first Black police chief of any state conservation agency nationwide.

But to Shareese Churchill, he was Dad, or “Doogas,” depending on the day. And, more than anything, he loved to cook. He was an expert at making pancakes with crispy edges and knew the perfect ratio of chocolate syrup to milk. He often made Churchill’s favorite meal — meatloaf, mashed potatoes and broccoli with cheese — but he was also known for seafood Fridays. And who could forget his specialty dessert, sweet potato pie?

A knack for cooking is one of the many things Churchill inherited from her father, and his homemade meals are one of the things she’ll miss most about him. DeLeaver, a proud family man who spent his life blazing trails for Black law enforcement officers in Maryland and across the country, died Oct. 16 of heart failure. He was 77.

DeLeaver was born Dec. 22, 1946, to the late James and Clara DeLeaver. He was the fourth of eight children — and the only one without a middle name. He grew up attending Baltimore public schools. At Paul Laurence Dunbar High School, he played golf and tennis.

An observant and thoughtful child, DeLeaver was also a bit of a prankster, said his younger brother, Rodney DeLeaver. When he was about 12, he put water cups at the bottom of the stairs on Christmas morning and laughed when the family kicked them over when coming downstairs to open gifts.

As kids, the two brothers dreamed of their future careers. Their father worked multiple jobs, and “we always thought that that was such a hard life,” Rodney DeLeaver said. Douglas DeLeaver didn’t have a particular vocation in mind but knew he wanted to do something “professional,” his brother said.

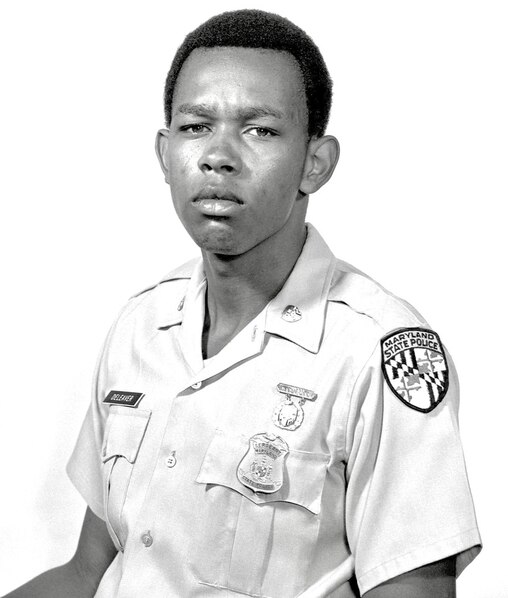

Following in the footsteps of his older brothers who served in the military, DeLeaver enlisted in the Army in 1966 and was honorably discharged in 1969. When he returned, a chance meeting with a police officer on the side of a highway prompted him to enroll in the Maryland State Police Academy, Rodney DeLeaver said. He graduated in 1970, becoming the 13th Black officer to join the state police force.

It was an accomplishment that did not come without challenges. In the early 1970s, and throughout his career, DeLeaver faced racism in and out of state agencies, said Mike Zeigler, a former state trooper and one of DeLeaver’s best friends. But he tried to stay upbeat and just do a good job, Zeigler said.

“If you perform at a high level, you can’t be denied,” Zeigler said, describing DeLeaver’s mindset. “Performance has no color barriers. They will try to knock you back down two feet, but you just keep coming back up.”

Churchill grew up thinking her father was the best at everything — and that may have been true — but he didn’t work hard just to be the best, she said.

“He wanted to be in a position where he was able to help others,” she said.

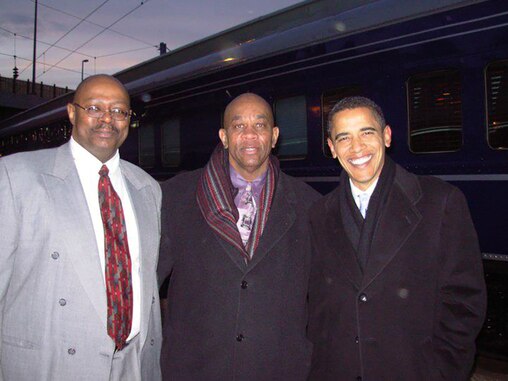

Zeigler met DeLeaver when he joined the state police force in 1976. As Zeigler rose up the ranks, DeLeaver became a mentor to him, as he was to many officers, especially African Americans, throughout his career. He didn’t often talk about uplifting others — he just did, Zeigler said.

“He’d just slide in there and put somebody under his wing and take them up the ladder with him or pull them along,” Zeigler said. “He’d be encouraging: ‘You can do this.’”

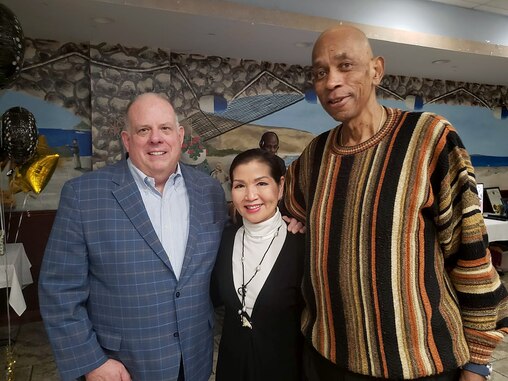

DeLeaver was a forward-thinking leader, Zeigler said, and wanted to improve the lives of those around him. People were naturally drawn to him, and he seemed to know everyone, family and friends said. He would often come home from running errands with stories about his “friends” behind the checkout counters.

Churchill said one of the biggest lessons she learned from her father is to always ask people how they are “and stick around for the answer.”

DeLeaver had a 22-year run with the state police, which included executive protection for Govs. Marvin Mandel, Blair Lee III and Harry Hughes. His career was wide-ranging — he worked in narcotics, contract murders, hostage negotiations, equal employment and other areas. He didn’t often fire his gun, Churchill said, but she recalled one story about a drug bust that ended with him shooting a criminal in his rear end.

It was a story that could have come straight out of the TV cop shows DeLeaver would watch. “Hill Street Blues” and “COPS” were among his favorites.

DeLeaver went on to work for several other state law enforcement agencies, including the Maryland Transportation Authority Police and the Maryland Transit Administration Police. In 2003, he was appointed superintendent of the Natural Resources Police, becoming the first Black police chief of any state conservation agency in the United States.

Later in life, he worked in the private sector, including as president of DeLeaver & Associates, where he advised the U.S. Department of Homeland Security on mass transportation.

Though the jobs changed, DeLeaver’s commitment to his family never did. He was a devoted husband to Margie Washington, whom he met early in his police career. He’d seen her picture while visiting a friend’s house and asked for an introduction, their daughter said.

When they met in January 1974, DeLeaver picked her up from a bus stop in a gold Monte Carlo — a flashy car with a swivel seat — and took her to work, Churchill said. They fell in love quickly and eloped that April. They marked a half century of marriage this year.

Churchill was the couple’s only child, and there was “no bigger cheerleader in my life than my dad,” she said. DeLeaver guided Churchill, who works in communications in the Maryland State Treasurer’s Office, on her path to a career in state government. He was known to sing his daughter’s praises.

After DeLeaver died, Maryland Comptroller Brooke Lierman reached out to tell her about the first time she’d met her father a few years back. “Do you know who my daughter is?” Lierman recalled him asking early in the conversation. Lierman, then a state delegate, admitted she didn’t, so DeLeaver spent the next five minutes talking about her.

DeLeaver was equally proud of his “Poppy” status to granddaughters Isabella and Avery, whom he would entertain with jokes, elaborate breakfasts and a hand slap game he called “Woozy Woozy.”

Since DeLeaver’s death, hundreds of people have shared condolences and memories of him online. There is a public viewing scheduled for Oct. 29 from 4 p.m. to 7 p.m. at the March Life Tribute Center in Randallstown, followed by a wake there the next day from 10 a.m. to 11 a.m.

Rodney DeLeaver said the outpouring of love and support is no surprise.

“We experienced it first,” he said. “The care and nurturing that he showed us, he showed to everyone.”

The Banner publishes news stories about people who have recently died in the Baltimore region. If your loved one has passed and you would like to inquire about an obituary, please contact obituary@thebaltimorebanner.com. If you are interested in placing a paid death notice, please contact groupsales@thebaltimorebanner.com or visit this website.

Comments

Welcome to The Banner's subscriber-only commenting community. Please review our community guidelines.