George “Doc” Manning credited his mother for his love of jazz and his father for his love of live music, but the way he shared that love was all his own.

Manning was a familiar face — and voice — in Baltimore’s jazz scene. He frequented gigs across the city and emceed shows at An die Musik Live. For nearly three decades, he hosted a weekly jazz show on Morgan State University’s radio station, WEAA. Though he didn’t play any instruments, he was a performer in his own right.

“Doc would set the atmosphere, tell you what you’re about to hear, tell you why what you’re about to hear is important,” said Lafayette Gilchrist, a jazz pianist and Manning’s longtime friend. “Doc felt like it was important to give it a platform in terms of presentation.”

Gilchrist hasn’t performed a show for more than two weeks now. It’d just be too weird to look out into a crowd that doesn’t include Manning, he said.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

Manning, who shared his encyclopedic knowledge of jazz and organized shows to promote the music he adored so much, died Dec. 24 of heart failure. He was 74.

“He was a professor of jazz studies, and he just believed that it was something that should be preserved and cared for and promoted,” said Manning’s wife, Michelle Frazier. “He was upset that people didn’t see the role that it played in history and how important it was of a genre to the music industry, to the music world.”

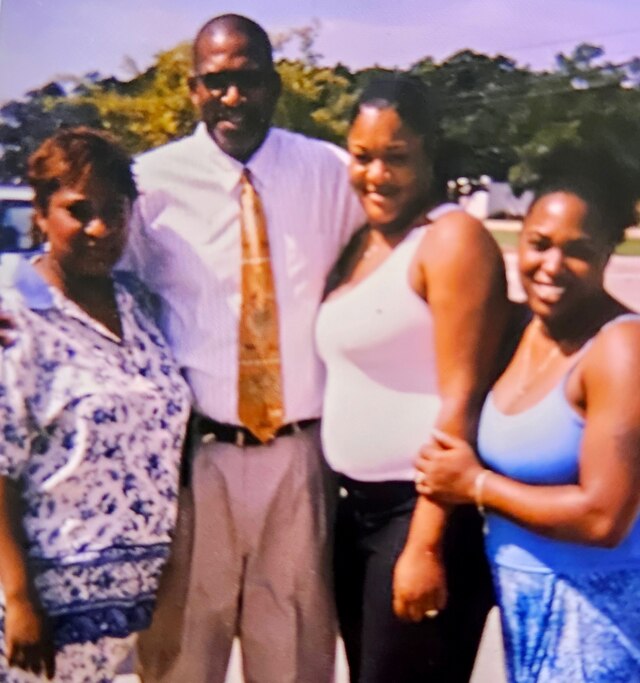

Manning was born on July 11, 1950, and grew up in a West Baltimore rowhouse, Frazier said. He was the third of eight children, each two years apart — Christine, Loretta, John, Shirley, Joanne, Larry and Jerome. Growing up, he sometimes worked in the shipyard with his father or at the neighborhood grocery store, Frazier said. His family called him “Smiley” because he was grinning all the time.

Manning’s mother taught him about jazz, and his father often took him to hear live music at Carr’s Beach, the Chesapeake Bay resort that served as a refuge in the Jim Crow era. The beach drew R&B greats, including Ray Charles, Stevie Wonder and James Brown, who greatly influenced Manning, Frazier said.

Manning lived in a close-knit neighborhood, Frazier said, where everybody looked out for each other. He always kept a friend and spent many of his days playing basketball at different courts around the city, she said.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

“He’d meet different people, and he just became this universal person,” Frazier said. “He never had any problems with who a person was, where they came from, what their religion was, what their race was, ethnic group, any of that — he was just a diplomat.”

When Manning was 18, he enlisted in the Army. He was a combat medic and was deployed to Vietnam during the war, where he earned the nickname “Doc.”

His time in Vietnam would give him nightmares years later, Frazier said. But music was still a source of comfort during his service — he’d often listen to blues and rock while overseas, she said.

When he came home, he worked some odd jobs and went in and out of school, Frazier said. He married Gloria Kinsler in 1974 and had two stepchildren, Eric and Cheryl, from that union. Kinsler died of cancer in 1982, Frazier said.

When Frazier and Manning met in 1976, Manning was back at Coppin State University to earn his bachelor’s degree in political science, and Frazier was an associate professor. They quickly formed a friendship over their shared love of jazz. For decades afterward, they enjoyed a platonic relationship, even making a pact that they would marry each other if they didn’t find a partner worthy of a wedding.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

Manning had a friend who worked at Morgan State University’s radio station, WEAA, who helped him get in the door there and eventually start his own radio show. “In the Tradition,” nodding to Amiri Baraka’s poem of the same name, started airing every Monday in 1989, according to the Jazz Journalists Association. The show ran for 28 years before WEAA made sweeping programming changes in 2017, the AFRO reported.

“Doc was much beloved at WEAA and by the greater Morgan and Baltimore communities,” said Jacqueline Jones, the dean of the School of Global Journalism & Communication at Morgan State University. “He came back for a special show on WEAA in 2021, with host and station manager Robert Shahid, and the phones blew up with callers who wanted a word with Doc. He will always be a fan favorite of those who knew and remember him.”

In 1990, Manning met Henry Wong as he was working to open a music store, An die Musik, in Towson. Manning worked nearby at the time, and Wong was so impressed by his knowledge and passion for jazz that he asked him to work with him. He was a jazz specialist, booker and emcee.

When the store moved to Mount Vernon in the early 2000s and started to focus more on live music, Manning was the natural hosting choice.

“It’s kind of like his home away from home,” Wong said. “He enjoyed the times, he enjoyed the laughter, he enjoyed a few glasses of wine.”

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

After Manning’s death, Wong named one of the stages at An die Musik after him. He also plans to host a celebration of life at the venue sometime in the spring.

Manning met hundreds of people through his hosting work, often developing close friendships and mentoring some. He was generous with his connections and always made sure to support local musicians, said Gilchrist, the jazz pianist and friend.

“Doc had a strong, gentle character, but very principled,” he said. “If Doc gave you his word, his word is good as gold. If Doc says, ‘We can be doing this and it’s going to get done,’ you can take it to the bank.”

Gregory Thompkins, a saxophonist and another longtime friend, said Manning was always encouraging and thoughtful, often going out of his way to attend gigs and help where he could. In 2007, one of Thompkins’ saxophone students started a nonprofit, the Baltimore Jazz Education Project, that Thompkins now runs.

“Doc stepped forward, and he would have me come on the show and talk about the organization and help us fundraise so that we could provide instruments and lessons for underserved kids in the Baltimore area,” Thompkins said.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

And though his heart belonged to jazz, Manning was a fan of all kinds of music. When Shodekeh Talifero moved to Baltimore in 2002, he came as a hip-hop artist, but the pair still developed a rich friendship.

“He still greeted me with a very warm welcoming as a jazz ambassador of the city,” Talifero said. “He was never condescending. He was open to how I approached the music, even though it wasn’t jazz.”

In his personal life, Manning finally began a romantic relationship with Frazier in 2008 — and then they broke up. The next year, they decided to try again, and Manning moved into her house. They’ve been together ever since and, at Manning’s insistence, tied the knot in 2021. Manning served as a stepfather to Frazier’s son, David Frazier-Jacobs.

In more recent times, before Manning fell ill with lung cancer and heart problems, he and Frazier would spend mini-vacations in Washington, D.C., frequenting the Blues Alley jazz club and staying overnight at a hotel instead of driving back to Baltimore.

“I knew I was the one for him because I knew who he was,” Frazier said. “I accepted him for everything. Anything that he gave out, I accepted, because he was just a genuinely kind, considerate man. He was a gentle soul.”

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

The Banner publishes news stories about people who have recently died in Maryland. If your loved one has passed and you would like to inquire about an obituary, please contact obituary@thebaltimorebanner.com. If you are interested in placing a paid death notice, please contact groupsales@thebaltimorebanner.com or visit this website.

Comments

Welcome to The Banner's subscriber-only commenting community. Please review our community guidelines.