Glenard “Glen” Middleton Sr. was a fighter.

Maybe it was in his blood — his brother, Larry Middleton, was a heavyweight professional boxer, and Middleton was his sparring partner. Or maybe it was just because he felt a calling to help others and create a more just world.

Maybe it was a little of both.

Middleton, a well-known and respected Maryland labor leader and a relentless advocate for marginalized communities and undervalued workers, fought until he couldn’t anymore. He died on Nov. 7 from complications of diabetes. He was 76.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

Middleton was born on Aug. 11, 1948, the middle child in a family of seven children. His parents started to raise their family in Cherry Hill before moving to Turner Station, a historic Black neighborhood in Baltimore County where many Bethlehem Steel Shipyard workers lived. Middleton’s father was among them, while his mother was a homemaker.

As Middleton aged and became influential in local politics, he never forgot where he grew up, said his wife, Baltimore City Councilwoman Sharon Green Middleton. “He always made a point to visit people there,” she said.

As a child, Middleton was something of a “bad boy,” but he was still the only child to help his mother clean up the house late at night, Sharon Green Middleton said. He grew up alongside now-U.S. Rep. Kweisi Mfume, a lifelong friend who praised Middleton’s “tenacious work ethic and sense of fairness.”

“Glen loved his family, cherished his friends and didn’t suffer fools lightly,” Mfume said in a statement. “He constantly defied the limits of others’ expectations and gave us an example of perseverance that made us all the better for having known him.”

Middleton found his calling early in life, his wife said, as he started his career in his early 20s as a correctional officer for the Baltimore City jail. There, he became a union representative with the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME), introducing him to the world of labor rights.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

He also introduced himself to Sharon Green Middleton. She was a high school teacher, and the two happened to meet at a college graduation. She was drawn to his caring and helpful demeanor, and the couple started dating three or four months later.

“We would go on a date, and if there were two people arguing on the street, he’d stop and park the car and go and break up the fight,” she said. He would give the coat off his back to a stranger. “He just had a heart of gold,” she said.

He also had a special way of persuading people and getting his way, Sharon Green Middleton said. Take, for example, his proposal to his wife: The couple sat down for Thanksgiving dinner at her aunt’s house, and when it was time for dessert, Middleton turned to his girlfriend’s father and asked if he could marry her. Everyone got quiet and looked at Sharon Green Middleton, who was just as shocked as everyone else.

“He asked my father and didn’t ask me!” she joked. But it was a ‘yes’ either way.

“He figured out ways, for anything, to get ‘yes’ for his answer, and he would do that whether it was with me or things with the union,” Sharon Green Middleton said. “He was very creative.”

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

The couple married in 1979 and celebrated 45 years together earlier this year. Sharon Green Middleton credits her husband’s attentiveness, enduring support and commitment to never go to bed angry for their happy marriage. They bore a son, Glen Middleton Jr., and he also had two daughters, Otesa and Anika, from a previous relationship.

They also had a dog, Bruce, that Middleton brought home about six years ago after eyeing him for two weeks at a local shelter. Sharon Green Middleton thinks it was part of a long-term plan to make sure she wouldn’t be alone after his death — that’s just the kind of person he was.

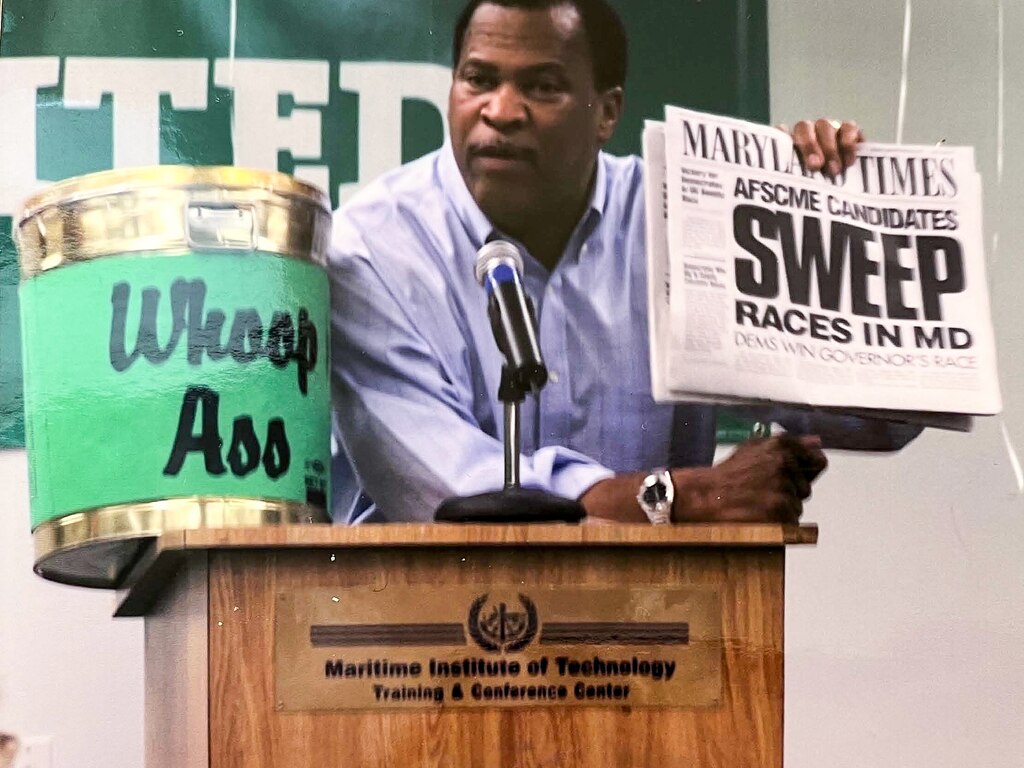

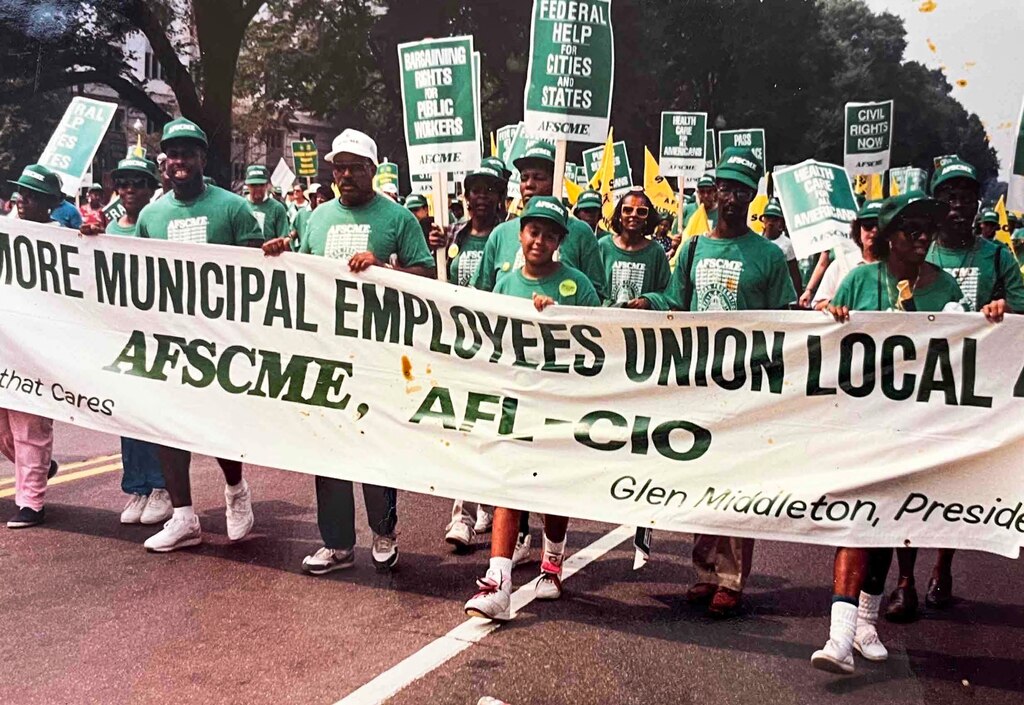

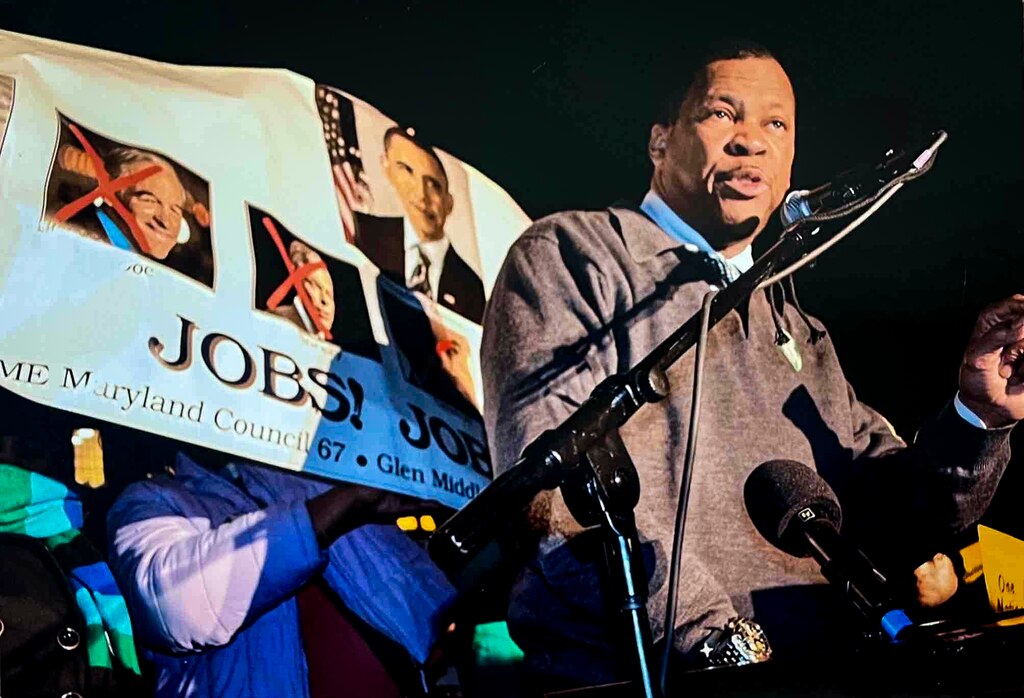

Middleton worked his way from shop steward to president of the Baltimore Municipal Employees, AFSCME Local 44. In 1990, he became executive director of AFSCME Council 67, the first African American to hold the position. Six years later, he also took on a role as AFSCME’s international vice president, representing D.C., Maryland and Virginia.

AFSCME International President Lee Saunders said Middleton was a “tenacious trade unionist” who “spent decades fighting for the rights of public service workers.”

“When you walked down the street in Baltimore with Glen, no matter what neighborhood you were in, folks knew him and would greet him,” Saunders said in a statement. “The respect and admiration he enjoyed in the community was what made him one of a kind.”

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

Middleton was heavily involved in Democratic politics and helped elect leaders up and down the ballot. (“If you had Glen Middleton behind you, if you were running for office, you always win,” his wife said.)

Dorothy Bryant, the current president of AFSCME Local 44, said Middleton was someone who was “always in your corner.” They met decades ago at a union meeting, and Middleton believed in Bryant right away, making her the chief shop steward for the union.

Bryant was the first woman to hold the position and said she learned many things from Middleton. Above all, though, “he cared so much about the membership, and all he wanted was the best, as far as safe working environments and making sure that they got compensated for the work they did,” she said.

“He would fight, fight and fight for the membership,” Bryant said. “No fights became too big or too small that he wouldn’t stand up for it.”

Patrick Moran, the president of AFSCME Maryland Council 3, recalled the time Middleton helped save hundreds of jobs when he opposed former Gov. Robert Ehrlich’s proposed state takeover of Baltimore City schools about two decades ago.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

“There’s so much honor and dignity in work, and he knew that, he fought for that, and as a result, those people continued to work and hold their jobs and hold their families and communities together,” Moran said.

Middleton’s concern for others was also evident in his care for children, especially his own. Once, when Glen Middleton Jr. was young, he had a piano recital. Middleton was so busy that by the time he arrived, he had missed his son’s performance — so he convinced the teacher to let the young man do it again.

The father and son often played football together, a cherished pastime for Middleton. He’d always been athletic, playing basketball and baseball, and he’d earned a football scholarship to attend Virginia Commonwealth University in his youth. He was a big fan of the Baltimore Ravens and Orioles, his wife said.

Middleton was also a devoted Christian and a very faithful man, always saying grace before eating a meal and praying before bedtime.

“He was an overall gentleman and loved his family, loved his extended family — just a good person to be around,” his wife said. “He always had that feeling to want to show you a good time. He got his energy from making sure that people were happy.”

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

Middleton never wanted to burden others with personal issues. That became especially apparent as his health declined, and he avoided talking about it with others.

On the day he died, Sharon Green Middleton knew it might be the end. He’d been holding on for so long, and his breathing had grown heavy. She leaned over and whispered in his ear, “Glen, you need to rest. Glen Jr. and I are going to be fine.” He died two hours later.

“I looked at his face, and he didn’t have any wrinkles on his forehead,” his wife said. “It was like all this stress was gone.”

The Banner publishes news stories about people who have recently died in Maryland. If your loved one has passed and you would like to inquire about an obituary, please contact obituary@thebaltimorebanner.com. If you are interested in placing a paid death notice, please contact groupsales@thebaltimorebanner.com or visit this website.

Comments

Welcome to The Banner's subscriber-only commenting community. Please review our community guidelines.