As Dr. Jeremy David Walston listened to the sounds of Ho Chi Minh City, he watched in awe as his adopted newborn son took a nap. Inspiration struck, and he began to pen a letter.

In his professional life, Walston focused on older adults. His thoughts were often consumed with questions of how to improve the quality of life or slow the progression of disease. But, on this day in 2002, all he could think about was the baby. So he wrote to him, to let his son know how much he was loved from the very beginning of his life, even before Walston and his longtime partner brought him home to Baltimore.

“We will do our best to make a happy and lovely family for you, and we will take great pride in helping you explore the world and in becoming a happy, healthy member of the community of the world,” Walston wrote.

Years later, when his son read the letter for the first time, he cried. When Walston’s husband, George Lavdas, read the letter aloud last week, he swallowed tears, too. Walston is gone now, but his love is forever etched in the loops of his O’s and the dots over his I’s.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

Walston, a Bolton Hill doctor who studied geriatric medicine and founded the Johns Hopkins Human Aging Project, died June 10 of glioblastoma, an aggressive form of brain cancer. He was 64.

He was born April 7, 1961, in Ohio to Gene and Genevieve Walston. He was sandwiched between an older brother, Perry, and younger sister, Wendy — a typical middle child, his sister said, who was definitely a bit of an instigator.

Read More

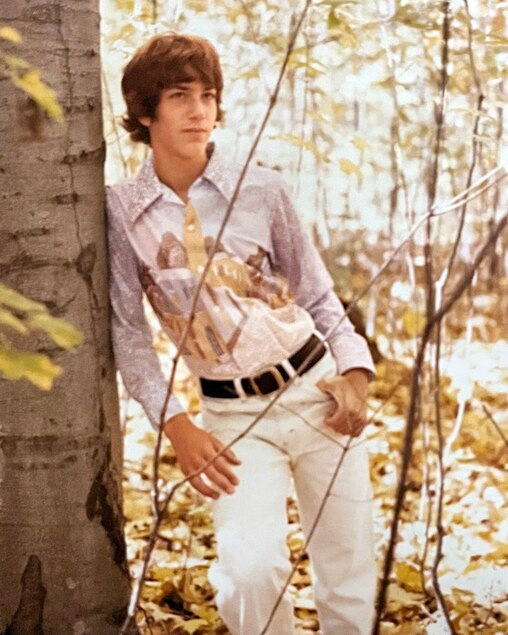

Walston always described his childhood as “idyllic,” his loved ones said. All the families knew each other in their small town, and the kids would often swim or ride their bikes together before dinner. They lived near the woods and a small river, so Walston spent much of his time exploring trails and admiring nature.

He often visited his grandparents, who lived on a farm nearby. Later, the family moved onto the property, where Walston loved the easy outdoor access. He was a Boy Scout, and he followed in his father’s footsteps as a birder. As a teenager, he worked as a lifeguard at the local pool.

In school, he was a straight-A student with a nearly photographic memory, Wendy Walston Vaughn said. He was a member of the National Honor Society and the yearbook club, and he played trumpet in the marching band.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

He spent a lot of time in his youth around older people, mostly his relatives, who influenced his career in geriatric medicine, loved ones said. In high school, he started working at a local nursing home.

“He liked talking to older people,” Walston Vaughn said. “He was interested in them. He was interested in how the body breaks down and why it does what it does.”

He earned a bachelor’s degree from Capital University in Columbus, Ohio. College brought him new friends and experiences, along with the opportunity to explore his sexuality. He thought he might be gay, but he struggled to come to terms with it, his husband said. Walston needed a change of scenery, so he headed to Ann Arbor, Michigan.

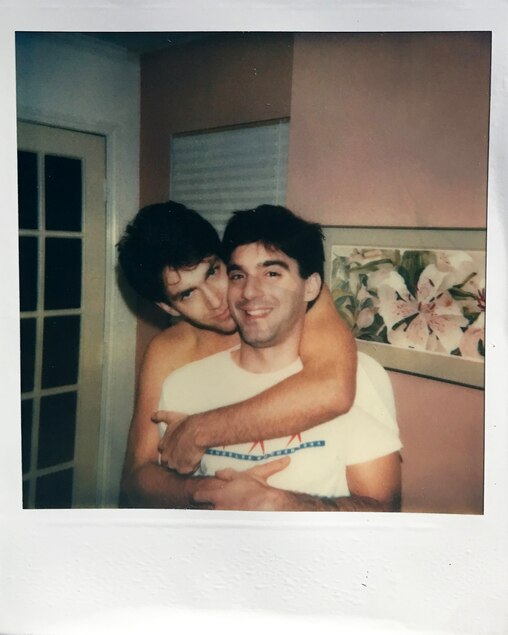

In 1982, he attended an event for gay students at the University of Michigan Law School. There, he met Lavdas, then a first-year law student.

Lavdas thought Walston was “a cutie,” and after the event they went out for coffee. When they returned to Lavdas’ room, he told Walston, “I’m enamored with you. Can I kiss you?” And Walston said yes.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

After they kissed, they sat in silence for a moment. Lavdas remembers saying, “Oh my God, that was intense.” It was the beginning of a 43-year love story.

Lavdas followed Walston as he attended medical school at the University of Cincinnati and completed his residency at the Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, the job that brought the couple to Baltimore. They picked a rowhouse in Bolton Hill.

Walston was immediately a member of the Hopkins community, and he never left. He also completed a fellowship at Hopkins and conducted research focused mainly on resiliency and healthy aging. He went on to found the Human Aging Project, serve as deputy director of the Division of Geriatric Medicine and Gerontology and become the principal investigator of the Older Americans Independence Center.

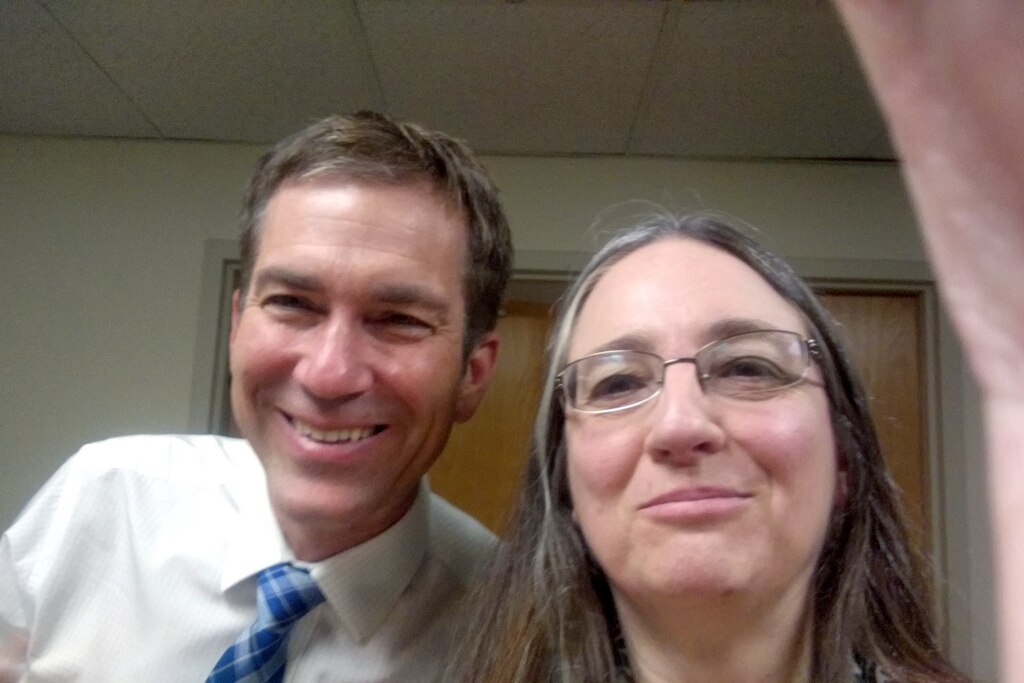

Karen Bandeen-Roche, a close colleague who led the Older Americans Independence Center with Walston for 17 years, said he was a dedicated clinician and a knowledgeable researcher — a rare combination in the field.

“His legacy is a very human brand of scholarship,” she said. “This demonstration of the ability to be an absolutely A1 top scientist, world leader in his area, while being generous and kind and improving the fortunes and the enjoyment of life of everybody that he worked with.”

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

He wanted to pass on those skills. Walston was a devoted mentor, Bandeen-Roche said, who was known to create opportunities for his mentees and fight for their successes. In April, Walston was presented the prestigious Dean’s Distinguished Mentoring Award at Hopkins’ medical school.

Yet, at 64, cancer robbed Walston of the opportunity to experience an age he’d spent his life researching.

But he made the years he had count, loved ones said. Walston always knew he wanted children, and he and Lavdas adopted two sons from Vietnam. Oliver and Alexander “Alex” Walston-Lavdas were the lights of his life, his husband said, and he found great joy in giving them new experiences and exploring the world with them.

Walston particularly loved traveling to Germany, where he and Lavdas spoke the native language. They taught it to their children. The family also took trips to Austria and Italy. Their travels spanned multiple continents.

At home, Walston was an expert chef, known for his delicious crab cakes and made-from-scratch sauerkraut. He hosted massive Christmas parties, even though Lavdas didn’t love that he was left with cleanup duties afterward.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

Age only deepened Walston’s love of nature, and he spent many early mornings tending to his garden in Druid Hill Park. He loved using the Merlin Bird ID app, which he always recommended to others, and was an unofficial butterfly expert, his sister said.

“I think it’s safe to say that he would tell people to garden a little more, reach out to your friends and family a little more and enjoy nature more often,” Walston Vaughn said.

As she spoke, a tiny butterfly — brown and black and a little orange — was perched next to her. It looked just like the one, she said, that came to her weeks before on the day her brother died.

The Banner publishes news stories about people who have recently died in Maryland. If your loved one has passed and you would like to inquire about an obituary, please contact obituary@thebaltimorebanner.com. If you are interested in placing a paid death notice, please contact groupsales@thebaltimorebanner.com or visit this website.

Comments

Welcome to The Banner's subscriber-only commenting community. Please review our community guidelines.