It was never hard to pick a gift for Richard Deasy. The answer was always bow ties.

Sometimes people would ask him how the colorful, patterned bows became a part of his signature look. The backstory was really never that complicated — he wore a bow tie once, and his wife, Kathleen Deasy, said it looked nice. From then on, it was all bowties all the time.

Kathleen Deasy still has many of them. They’re sweet reminders of the love of her life, who died on Oct. 24 from complications of dementia. He was 84.

Deasy, whose friends called him “Dick,” was born on Aug. 21, 1940, in Pittsburgh to John and Mary Deasy. He was both “left- and right-brained,” his wife said — equally artistic and analytical. He left a lasting impact on education and culture both in Maryland and nationwide.

Deasy was a former assistant state superintendent for instruction and curriculum in the Maryland State Department of Education and later the founding director of the National Arts Education Partnership, a federally funded program that promotes arts programs in schools.

Before he promoted and improved education for others, Deasy spent his early years achieving personal academic successes: He was a straight-A student and high school valedictorian who went on to earn a bachelor’s degree in English and religion from LaSalle University, where he was recognized as the most outstanding graduate.

In 1963, he earned a master’s degree in theology from the same school. He started his career teaching English and religion at La Salle College High School, a private school for Catholic boys. He was a proud Christian Brother, only leaving in the late 1960s to pursue a doctorate in philosophy at Princeton University. Social upheaval prompted him to leave about a year into his studies.

“He said, ‘What am I doing studying philosophy? I should be out there helping the world,’” Kathleen Deasy recalled.

Afterward, he returned to Pennsylvania to work as a reporter for the Daily Intelligencer in Bucks County. He earned a Pulitzer nod for a series on a slum housing development, and shortly after, he landed at the Philadelphia Daily News.

“He was always a beautiful writer because he was a clear thinker,” his wife said.

The couple met around this time through mutual friends. Someone asked if he could help Kathleen Deasy install storm windows, and the two became fast friends. One thing led to another, and they married in 1971 in their living room, surrounded by Kathleen Deasy’s four children, Suzanne, Jory, Christopher and Timothy.

At the Daily News, Deasy covered a contentious teaching strike with such nuance that he got a call from the Pennsylvania secretary of education offering him a job, his wife said.

“Education was always a thread in every job that he did, every position that he held,” Kathleen Deasy said.

So the transition was natural. While in Pennsylvania, he met David Hornbeck, who thought Deasy was incredibly sharp and kind. When Hornbeck moved to Maryland in 1976 to become the state superintendent of schools, “Dick was the only person I brought with me,” he said. Deasy settled in Baltimore.

Over the years, the pair grew close, as did their families. They often visited art museums together — “Dick was a lifelong art aficionado, really quite an expert,” Hornbeck said — and had many dinners where they would discuss education, international affairs, religion and politics.

“He brought together both the intellectual qualities to which many aspire and the caring qualities of being intensely interested in other human beings,” Hornbeck said.

One of Hornbeck’s most lasting impressions of Deasy, though, was his enduring love and respect for his wife, whose opinion he valued above all others. Once, Deasy commissioned a bust of Kathleen Deasy that he proudly displayed in their home.

“It wasn’t unusual for him, after all those years, to point that out and to remark on how beautiful she continued to be in all ways that beauty reveals itself,” he said.

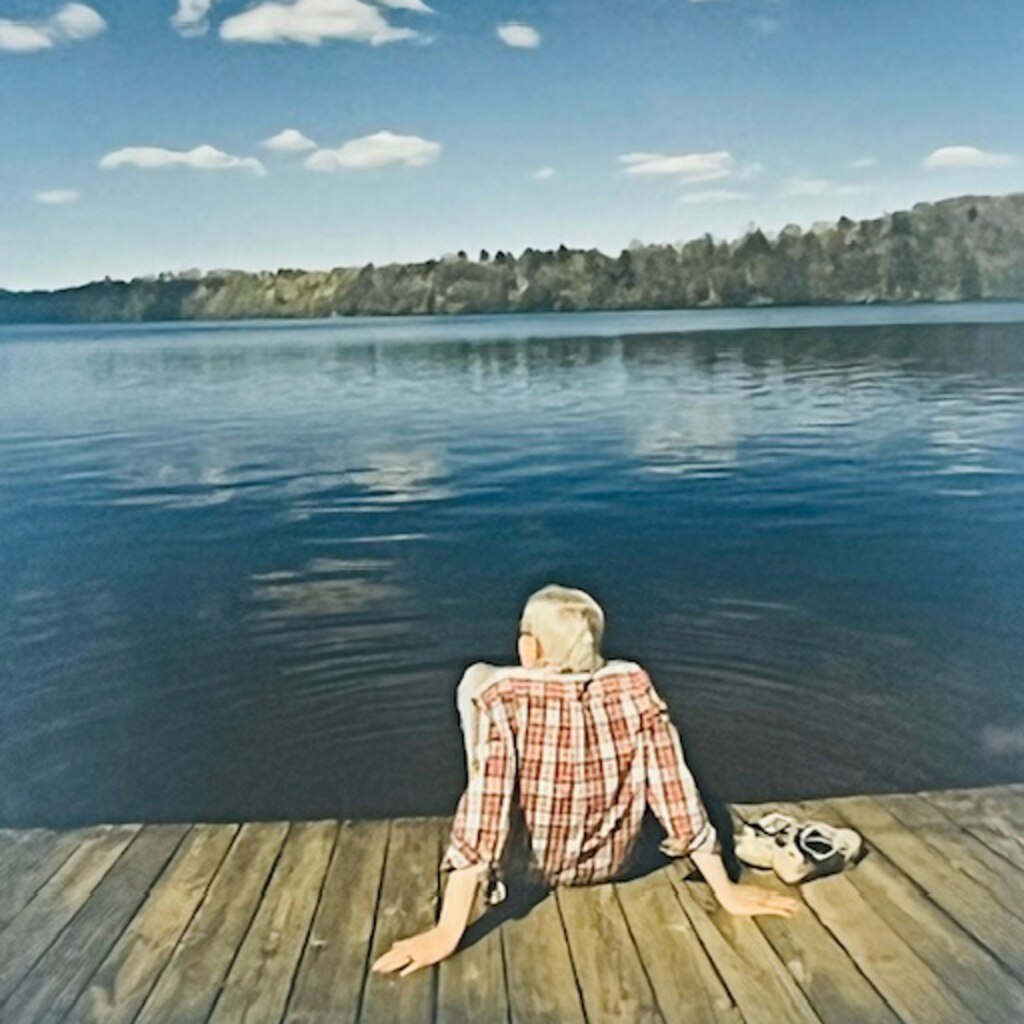

Deasy loved studying the arts, but he practiced them, too, his wife said. He was always doodling and took classes at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. The couple owned a Sears and Roebuck summer home in Eagles Mere, Pennsylvania, where Deasy spent 52 summers with watercolors and a paintbrush. He often painted for his wife, who especially treasures an abstract painting he made based on a dream.

The couple sometimes traveled abroad, and swimming in the Mediterranean Sea was a high point. Deasy was an avid swimmer who would “just glide through the water,” his wife said. He also enjoyed playing tennis and cross-country skiing and loved all kinds of music.

Deasy made a positive impact anywhere he went, family and friends said. That applied to Eagles Mere, too, where he joined the board of the Eagles Mere Conservancy and raised money to purchase and preserve local land. He was also a founding board member of the Eagles Mere Historic Village Inc., which helped modernize and upgrade local ice cream shops, restaurants and other businesses whose buildings had deteriorated over the years.

Last year, as Deasy’s health declined, other members of the board knew he could no longer attend meetings. So they unanimously honored him as a member emeritus — the first and the only.

The Banner publishes news stories about people who have recently died in Maryland. If your loved one has passed and you would like to inquire about an obituary, please contact obituary@thebaltimorebanner.com. If you are interested in placing a paid death notice, please contact groupsales@thebaltimorebanner.com or visit this website.

Comments

Welcome to The Banner's subscriber-only commenting community. Please review our community guidelines.