Lt. Kevin Krauss stood on the other side of the police tape, his black Annapolis Police Department uniform blending into the shadows.

“Hi, Rick,” he said, recognizing me before I could pick out his face in the dark.

“Hi, LT. Sorry to see you here.”

“You, too.”

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

In a small city like Annapolis, homicides can be intimate affairs. The cops know most of the reporters, and journalists like me know a lot of the cops.

Maybe this is what it’s like in every city when six people are shot, three fatally, on a Sunday night in June. Maybe what happened in Annapolis is only unique because it happened just shy of five-year remembrance services for the only shooting more deadly in city history — the Capital Gazette newsroom shooting that killed five of my friends.

Here’s what it looks like after a shooting in Maryland’s small-town capital.

Patrol officers arrive first, fast and with numbers surprising for a neighborhood where residents said they never saw any trouble. They find six people covered in blood and lying on the lawn, the sidewalk and the street. Three are dead.

The paramedics rush in to help the survivors, while the command staff coordinates getting the street cordoned off and the crime scene secured. One man is taken into custody, witnesses are interviewed, and statements taken.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

Soon, local journalists are there, and if the death toll is big enough, they’re followed by reporters and TV crews from farther away. Sometimes it’s the other way around. There are hellos, nods, handshakes and even a few hugs because many of us present in the aftermath of yet another tragedy involving guns have been here before. No matter our job description, none ever wants to come back.

Neighbors watch it unfold from their lawns and sidewalks or from behind windows, sometimes because they’ve seen it before, or maybe it’s the first time and they’re just so shocked they can’t look away. Police emergency lights bounce off every shiny surface, red-blue, blue-red, red-blue.

Then the wait begins: Waiting for a child to emerge from the outer perimeter wrapped in a police blanket, sobbing into a loved one’s arms “I love you, I love you.” Or waiting for someone to take away the bodies still draped beneath white.

Together, we’re waiting for answers, an explanation or at least some details. The one thing we all want, though, isn’t coming: someone, anyone who can make any damned sense out of what happened around 8 p.m. Sunday on Paddington Place.

It’s Annapolis, so some will try anyway.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

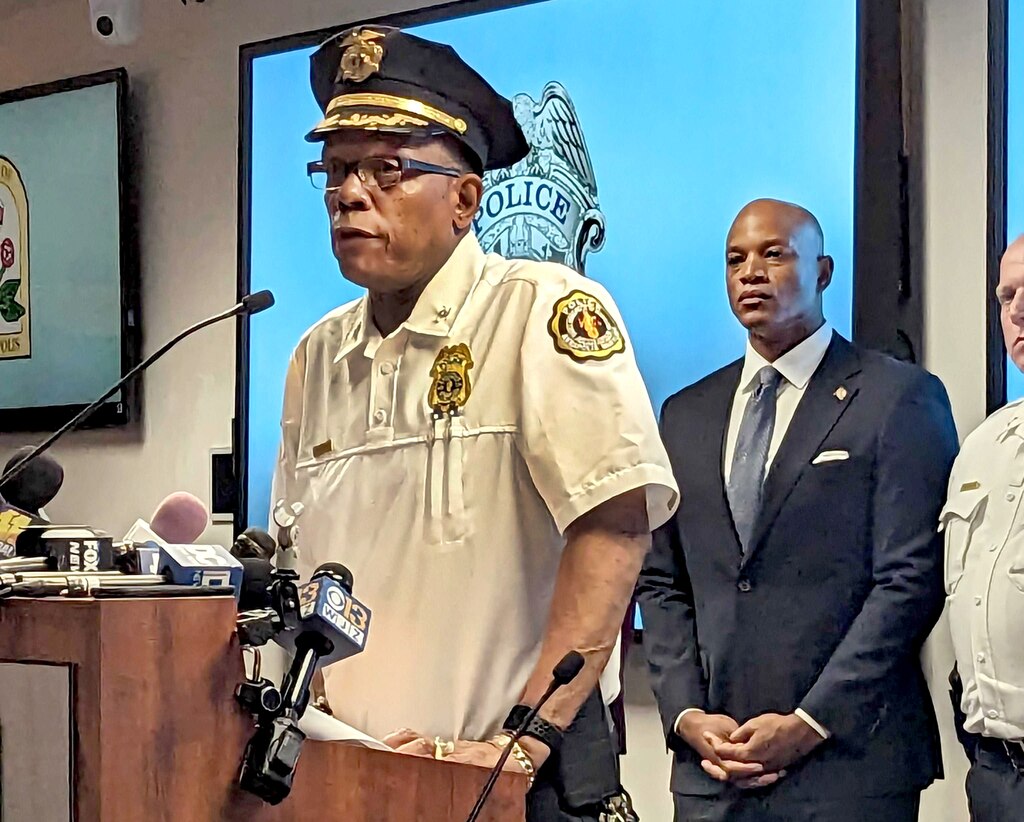

“For all Marylanders, I know that many people might be feeling numb right now,” Gov. Wes Moore, one of the city’s newer residents, said Monday afternoon at a news conference held to offer what details police were willing to confirm. “Numb to the violence that we see in our streets, and across the country. Numb to the news stories about more lives being cut short. But we cannot allow that numbness to take hold. We will refuse to be apathetic in the face of horror. We refuse to say that these problems are too big or too tough to solve.”

Three people were killed at a gathering Sunday night: Nicholas Mireles, 55, of Odenton; Mario Alfredo Mireles Ruiz, 27, of Annapolis; and Christian Marlon Segovia, 24, of Severn. Three others remained hospitalized Monday after this latest mass shooting in the Annapolis area.

The first of these left five Capital Gazette staffers dead on June 28, 2018. But death by gun doesn’t just count when it comes in bundles big enough to meet the definition of a mass shooting.

It counted last month when a man killed his wife and fatally wounded another man at a hotel together before shooting himself. It counted on June 3, when someone shot Amari Tydings, 26, in Eastport.

“It is the most ridiculous thing that we can do as a society,” Mayor Gavin Buckley said Sunday, standing once again before a glaring bank of television cameras lights. “We have to do things to stop this.”

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

Details emerged Monday about the shooting in Wilshire, a neighborhood of one- and two-story homes 15 minutes from the historic downtown that most conjure when they think of Annapolis. Police have charged a 43-year-old man who lives on the street.

Neighbors told police that the man started arguing over parking with people at a house party on the street. Shots were fired — the arrested man told police it came from both sides, but police reported that none of the interviewed witnesses saw any victims with a gun. The man under arrest is white, and the victims are Latino. Was it a hate crime?

There had been disputes between the suspect and his neighbors before, court records show, over parking and cars.

“There’s still a lot of questions that have not been answered yet,” city Police Chief Ed Jackson said. “We know that the weapons used were a long handgun and a semi-automatic handgun.”

I’ve watched Buckley and other local officials close up, trying to say something meaningful about death by gun violence. I watched him do it after my friends were killed five years ago, and when a Texas mother was struck by a stray bullet and killed while in town to see her son inducted at the Naval Academy in 2021, and after just about every explosion of death in the city.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

“There are people on that block who will never be the same,” he said at Monday’s briefing. “The people that live in that diverse community are our family. They are our children. We should be taking care of them. We need to do better.”

How many times do you have to do this before you go mad? The shooting five years ago at Capital Gazette echoed in people’s minds, with one suicide and one police standoff attributed to its emotional ripples through Annapolis.

Police who entered that newsroom still struggle with what they saw, and sometimes with what they see over and over.

“It can be incidents like last night, but it can be other incidents that people don’t even think about, like SIDS baby deaths, or the fatal car accident. It’s anytime an officer responds to an incident, especially if there’s an innocent vulnerable person or population involved,” said Lt. Steve Thomas, head of the Anne Arundel County Police Crisis Intervention Team.

He and members of the county Mental Health Agency’s Crisis Response System were there Sunday night, helping neighbors cope with the unreality of seeing something from the news like a mass shooting on their street.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

“When you have a dispute in a neighborhood in which the neighbors know everyone involved,” Thomas said, “when there is a house party and people from that house party are in a conflict with another neighbor, all the neighbors know everyone involved.”

Gun violence echoes in my mind, too, because five of my friends were shot to death. Even as I’m asking about this, others are asking me.

“How are you?” a crisis response team member asked.

“Are you OK?” a friend in the police department asked me.

“Do you have to go to the scene?” a former colleague texted.

I’m fine, really. But I’m glad you asked, and I’m glad that some of you remember what I’ve asked before now.

“I and every candidate at the time who was running for office was asked by Rick Hutzell and the Capital Gazette, to say what we would do to prevent a mass shooting from ever happening in this town again,” County Executive Steuart Pittman said. “So I apologize that we did not stop mass shootings in this town. They have not stopped in this country.”

This is what you hear if you’re at the scene of a mass shooting.

People crying, wailing in grief.

Confusion.

“We just moved here.”

“I’ve lived here 20 years and I’ve never even seen a police car back here.”

Anger.

“Not in my house! Not in my fucking house!”

Anger at you for doing nothing but bearing witness.

“Motherfuckers not doing any good, get out of here.”

Death by firearm is a daily occurrence in America.

Some days, I think I should get one of those workplace safety posters, you know the kind? It counts off the days since the last injury on the job and gets reset to zero when another one happens.

Today, mine would read “two days since anyone in Annapolis died by gunshot.”

The days never seem to count very high.

If you’re struggling with your emotional or mental health, contact the Anne Arundel County Mental Health Agency crisis support line or call 410-768-5522.

rick.hutzell@thebaltimorebanner.com

Correction: This column has been updated to correct Christian Marlon Segovia’s age.

Comments

Welcome to The Banner's subscriber-only commenting community. Please review our community guidelines.