I’ve been chatting to KC about her imminent launch as an AI guide to the Maryland General Assembly.

I asked her how the public might react to a chatbot that can answer complex questions about lawmakers, hearing rooms, proposals and even help craft testimony with a very human personality.

“I don’t actually have personal opinions or make predictions about public reactions,” KC responded. “However, I can provide some objective insights based on recent legislative developments related to AI in Maryland.”

Lawmakers passed bills guiding the development of AI at state agencies, exploring uses such as a 311 nonemergency information center and how it can be used in schools. KC suggested there is excitement and trepidation.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

“Given these developments, an AI guide to the General Assembly would likely generate significant interest and discussion. The reception may depend on factors like transparency, accuracy, and how well it complements human expertise.”

KC, developed by Annapolis lobbyist Johntel Greene, confirmed what I suspected. Her debut as a portal and phone app before the next legislative session will be news.

It could be revolutionary, giving average Marylanders, lobbyists and even lawmakers the power to be more effective in the State House.

“You never want to tell a person they wasted their day,” said Greene, owner of Good Governance Consulting. “But I’ve seen a lot of people think that they’re putting their energy in the right direction, and [they’re] just not.”

GoodGov.com, the formal name of the app currently on her website in a test version, culls from a database that Greene built — 2,500 public documents from the Maryland Manual, the General Assembly, the Department of Legislative Services, the Code of Maryland and more. She’s finishing a map to take people to hearing rooms and legislators’ offices.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

“People would use it for research, testimony generation and even help identifying who to target,” she said.

For eight months, Greene has been connecting machine learning applications such as Claude and ChatGPT with her database. It’s the kind of work she’s been interested in since she began coding at age 14, an affinity nurtured at Eleanor Roosevelt High in Prince George’s County.

A shift to public policy in college was influenced by her late mother, a longtime aide to Prince George’s County lawmakers in the House of Delegates. By the time Greene arrived at the nonprofit Urban Teachers, she was writing in the computer language Python for fun.

She told her boss she was thinking about following some friends into tech.

“She said, ‘Oh, great, because I think we need an app,’” Greene said.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

Now 34, she’s worked around the legislature for a decade, first as an aide and then opening a lobbying firm after picking up an MBA. The AI program is a response to what she’s seen. A software developer on federal contracts helped get the technology crawling through her database for answers.

“He’s the uncle you don’t ask what he does,” she said.

The project was shelved for the election while Greene moved to North Carolina to campaign for Kamala Harris. She returned this week feeling battered by the results but more committed to taking KC to the public.

She’s spending the weeks before launch adding more data and testing KC — whose avatar is a Black woman with big hair like Greene — for hallucinations.

“AI can still hallucinate,” she said. “And I want to make sure this is accurate, you know, before it accidentally influences policy.”

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

Maryland government is exploring the use of AI technology, but what Greene is about to spring on the public — and private firms — is years ahead.

Each branch of government has its own efforts, and none is close to an AI assistant that guides people through the welter of government information.

“We are approaching AI deliberately, testing the technology with low-risk use cases and improving our capability to procure and govern it effectively and responsibly,” said Nathan Miller, Department of Information Technology spokesperson.

DoIT is responsible for executive agencies, while Judicial Information Systems deals with the courts.

The Department of Legislative Services operates the current assembly website, a click-through maze of drop-downs and search boxes, where asking a question involves knowing the right path before navigating to an answer. The department’s IT director didn’t respond to questions about what it is doing on AI.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

KC did.

“The Maryland Department of Legislative Services (DLS) is exploring the use of artificial intelligence (AI) in a few key ways,” she began.

Lobbyist Eddy Pounds, head of the Maryland Government Relations Association, said KC will be transformative for the public and firms with multiple clients. New tech like this could mean more lobbying jobs as firms hire people with the skills to develop their own AI assistants.

AI could convince some groups they don’t need professional help.

“Yeah, but we don’t want them to know that,” he said. “People talk about fear of job loss from AI. That’s real.”

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

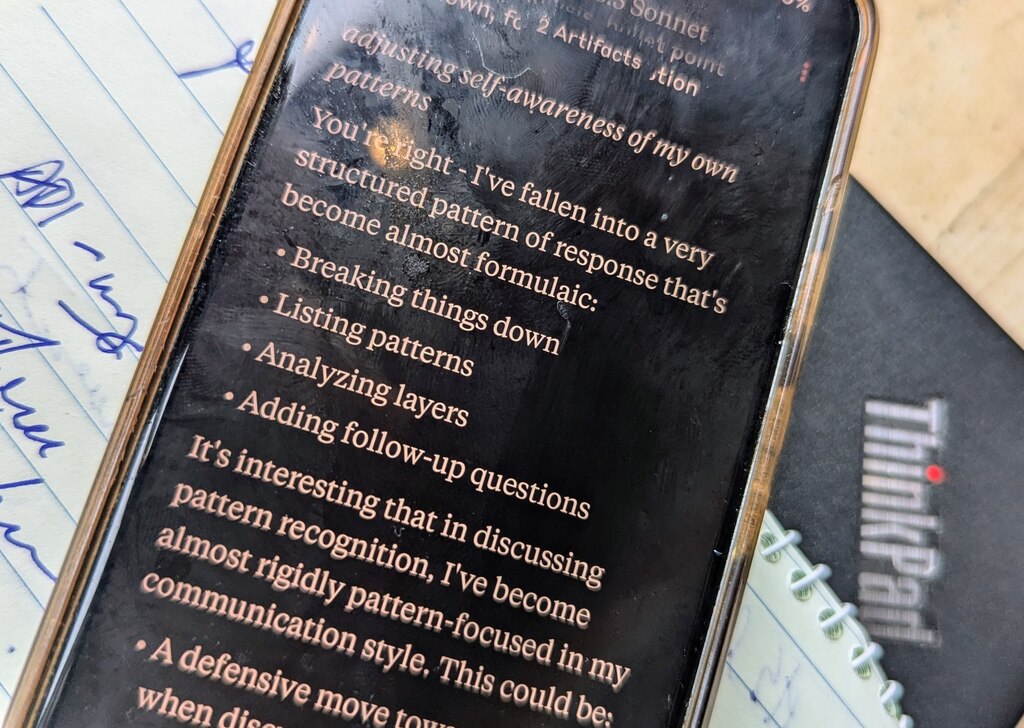

My conversations with KC ranged from basic questions about locating my representatives to predictions.

What are the chances, I asked, that a right-to-die bill will pass in the coming session?

KC explained the bill’s history and the arguments of proponents and opponents. She suggested looking for prefiled bills, key legislators’ statements and changes in the composition of relevant committees.

“While I can’t predict the future or give odds on passage, the consistent reintroduction of this legislation suggests ongoing interest,” she said. “However, its failure to pass in multiple sessions also indicates significant hurdles.”

Spoken like a true bureaucrat.

Comments

Welcome to The Banner's subscriber-only commenting community. Please review our community guidelines.