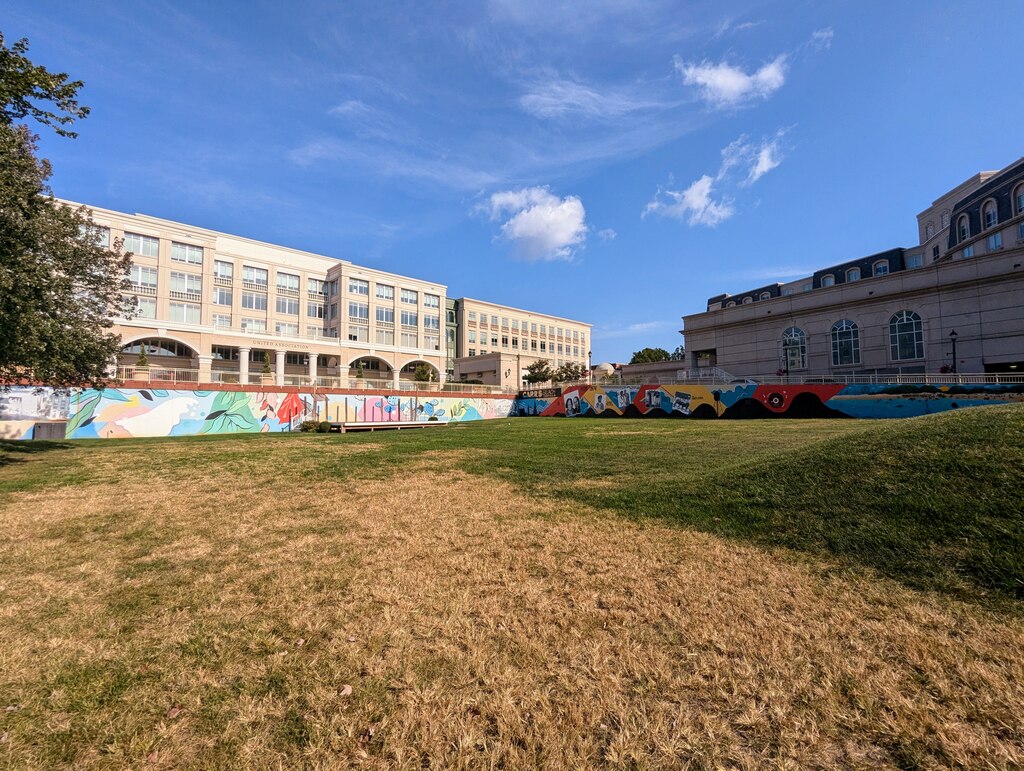

There is a “box” in the center of Annapolis. It’s invisible except for a rectangular patch of grass browning in a dry September.

Look up, and imaginary walls rise six stories. Look down, and they sink a few more into the sandy loam. Unlock the box, figure out how to use it, and a treasure worth more than $35 million a year could be inside.

The box is real estate. Developer Jerry Parks set 0.8 acres aside for the public 20 years ago in exchange for city permission to build a palatial mixed-use project on West Street that he named for himself, Park Place.

Planners said yes, happy to have a multimillion-dollar investment on what was once the desolate edge of downtown Annapolis. The box sounded like a good idea, too, even if it came with a catch — it must be used for a performing arts center.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

Nobody has figured out how to use the box. It remains a puzzle.

“It is. That’s absolutely true,” said architect Gary Martinez, who’s worked to solve it.

Now two nonprofits hope a third attempt to transform the vacant lot on Taylor Avenue, surrounded on three sides by a mix of commercial and residential luxury, will succeed where others have failed.

“There had been a lot of misinformation, confusion, all sorts of things that happened in those decades leading up to where we are now,” said Kristen Pironis, CEO of Visit Annapolis. “So we are committed to being really transparent and really open about those next steps. … We’ve got to make sure the community wants it.”

Together, the tourism promoter and the Arts Council of Anne Arundel County paid the Maryland Stadium Authority $60,000 to study the feasibility of a combined performing arts and conference center. The results were released just after Labor Day.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

If they can build public and financial support for a plan, Parks’ successor will provide the land for free.

“Kristen and I looked at each other and said, ‘Hey, why don’t we step up?’ ” said April Nyman, longtime president and CEO of the arts council. “I represent the arts community. Chris represents tourism, and I know that it would be very difficult for the arts community to sustain a large facility. … So, what better way to do a partnership?”

Parks, who couldn’t be reached for comment, wrote into the deed that the lot must be used for a performing arts center. He created the Maryland Center for the Performing Arts in 2008 to pursue the idea.

Frustrated at every turn, he handed off to the Maryland Cultural and Conference Center, or MC3, in 2021.

“It just couldn’t get off the ground,” said MC3 Chair Mike Davis, who’s been involved in the project from 2019. “He tried any number of different ways to do that and kept coming back, coming back. He hired lobbyists. He hired all kinds of people to try to work to get this thing moving.”

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

Both Annapolis and Anne Arundel County lent support, but not funding, to the new study. Visit Annapolis and the Arts Council commissioned the Maryland Stadium Authority, which hired Crossroads Consulting Services. The consultant found the same potential and problems that others studies had discovered.

There is a need for more space for the arts and tourism in Annapolis. The biggest facilities are at the Naval Academy; they can accommodate thousands but aren’t generally available for public use.

The largest theater in the city is at Maryland Hall, seating 725 people. The largest meeting spaces at hotels squeeze in a few hundred.

One of the problems that stymied previous efforts was a worry that building something new would only take away from what exists.

No one wants to hurt Maryland Hall, the former Annapolis High School that reopened as an arts center in 1979. Hotel companies, which fund Visit Annapolis and the Arts Council through a share of room taxes, jealously guard their share of the conference market.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

“We found that, rather than cannibalizing, we’d be able to expand the conferencing business, because it would be … larger than what we can currently accommodate in Annapolis,” Pironis said.

Now, leaders of Maryland Hall are interested in a possible partnership, perhaps managing the new performance space while freeing their stages and classrooms for more programs. There are also more people to serve. The county population has doubled since the arts center opened.

“Kristen, April and I share aligned interests,” said Jackie Coleman, executive director of the arts center. “We are looking to make all boats rise with our decision-making.”

The Annapolis Symphony Orchestra, the biggest single arts organization in the county, is interested too. At Maryland Hall, it’s constrained by the technology and space available in the converted high school. It conducted its own study to see if a new center down the street would meet its needs.

“When we look at what orchestras and symphonies are doing across the country, they are doing a lot of creative programming that brings music to people who wouldn’t necessarily otherwise go to a symphony concert — things like playing with movie music or actually bringing Cirque du Soleil performers on stage or gospel singers,” said Shelley Row, chair of the ASO Board of Directors. “We aren’t able to do any of those at Maryland Hall.”

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

A new center, the feasibility study found, could draw more than 113,000 people a year, with about two-thirds of them attending conferences, meetings and private events. That could shift Annapolis from being a weekend getaway for D.C.-based organizations to a regional player for longer conferences, filling hotels and restaurants.

Competition for that business includes Baltimore, Frederick, and, within Anne Arundel County, the Live! Casino and Hotel in Hanover. Its developers gave the county access to its multi-use space for high school graduations and other community events.

There is likely to be pushback. Venue owners and entertainment booking agents, who have their own lobbyists and friendly lawmakers, might oppose anything that would take away business.

The consultants looked at the potential economic impact, predicting that it would generate more than $35 million annually from direct spending and jobs, the ripple effect on other businesses as well as state and local tax revenues. It didn’t look deeply at costs.

The Montgomery County Conference Center cost $36 million when it opened in 2005. The same year, The Music Center at Strathmore opened at a cost of $100 million. Both are in Bethesda.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

Crossroads Consulting Services found that a combined space would be more expensive than a single-use building.

That’s because each purpose has unique needs. A 1,200-seat theater doesn’t easily convert to hold a few thousand conference-goers. The designers would also have to consider the neighbors. The parcel sits across a narrow city street from the Annapolis National Cemetery.

Martinez, the architect, has been turning all of this over almost from the beginning, developing different concepts. The solution, he believes, is to think about the site not as a horizontal plane, but as a box that reaches six stories up and several stories down. It could incorporate parts of Parks Place that are vacant.

Nyman and Pironis, whose organizations would benefit from increasing hotel taxes, are looking for money for another study to determine exactly what could be built on the site.

“Before we go to a next study, no matter the price of it, what we really have to do is bring the stakeholders, especially the art stakeholders, around the table and go through those list of next steps and go through those lists of concerns and say, ‘Can we get beyond this?’ ” Pironis said.

There is one more challenge. If the new partners cannot solve the puzzle by 2045, the box at the center of Annapolis goes back to MC3.

“I would think that anybody who would be taking a look at it would have to understand it’s almost like a Rubik’s Cube,” Martinez said.

Comments

Welcome to The Banner's subscriber-only commenting community. Please review our community guidelines.