At a gathering in Annapolis, fishery managers from 15 East Coast states searched for a cure to the dwindling object of their affection, avarice and ire.

What to do about rockfish?

Six years of frighteningly low numbers in the Chesapeake Bay — where 75% of the fish, also called striped bass, spawn before heading to the Atlantic Ocean — and a year after new curbs were put on the recreational and commercial catch in hopes of a rebound, the science was murky.

For six hours on Wednesday, the Atlantic Striped Bass Management Board studied bar graphs and fever charts projected onto conference room screens and listened as scientists explained what they meant. The hoped-for rebound wasn’t showing up.

“The technical committee is really struggling to predict what [the population of fish] is going to be in 2025,” said Gary Nelson, a Ph.D. from Massachusetts who led this year’s assessment of the rockfish population.

Please, members of the fishing public asked, no more cuts. Protect the struggling charter industry.

“We know at least 52 of these boats are up for sale and their businesses closed,” said Mike Smolek, captain of the Penny Sue in Edgewater and president of the Upper Bay Charter Association.

Blame recreational anglers, one board member thundered. Protect the landlubbers who love a good fried rockfish sandwich.

“They have no boat, but they do appreciate the taste of rockfish now and again,” said Robert T. Brown, president of the Maryland Watermen’s Association. “And we provide it for them.”

Wait to take more action, another warned, and it may be too late.

Protect the rockfish, now.

“We are running out of time,” said David Sikorski, executive director of the Coastal Conservation Association.

In the end, a majority of the board, part of the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission, agreed. They voted to hold a special session in December and decide on cuts.

By then, the technical staff hopes to better understand what’s going on in the waters of the Chesapeake and out in the Atlantic. Options for 2025 include changing the season, catch limits and size restrictions — or some combination of all three — to reduce the harvest of a cultural and economic touchstone by about 15%.

“It’s such a crucial species, not just in the Chesapeake Bay, but along the East Coast,” said Allison Colden, Maryland executive director of the Chesapeake Bay Foundation.

The challenge for the commission — which puts more effort into striped bass management than for any other species — is to ensure there are enough to go around by 2029. Right now, there’s only a 50% chance of making that target.

“Most of us going into this meeting expected some sort of action,” Colden said.

Everyone has their favorite explanation of why surveys of young fish in Maryland and Virginia, conducted by seining minnow-sized stripers out of spawning waterways, are so abysmal. The last six years have been among the lowest in 66 years of records.

Other states have it worse. North Carolina hasn’t seen stripers in its Pamlico Sound in a decade. New Jersey stopped surveying seven years ago.

It could be climate change warming the waters of the Chesapeake and making it harder for rockfish eggs to survive. It could be lack of menhaden, the tiny herring that rockfish find delightful, which is being scoured from the bay by commercial fishing in Virginia.

Pollution might be to blame. Maryland watermen point the finger at Baltimore’s leaky sewer treatment plants or releases of spring floodwater from Pennsylvania through the Conowingo Dam.

Maybe predators are eating all those yearlings before they grow big enough to swim the ocean and eventually return to reproduce. Watermen blamed the return of hungry dolphins to the middle bay, the rise of hungrier blue catfish and the even more ravenous double-crested cormorants.

“The amount of cormorants has been so bad, I’ve had to rebuild my dock two times, and the trees are devastated by their nesting,” said Rob Newberry, chair of the Delmarva Fisheries Association and a charter captain on Kent Island.

The science, however, is clear about at least one thing.

Rockfish have been overfished despite cuts in catches and even a ban in the 1980s. More has been taken out than is going in. Rebounding from that — if it can happen at all — will take years.

And, painfully for many, that means less fishing.

“It’s up to you to look at the numbers and look at the data and decide what level of risk you’re willing to accept,” Katie Drew, leader of the commission’s stock assessment team, told the board.

Members of the commission and their technical experts try to understand rockfish using science leavened with common wisdom and economics.

It’s not easy. You can’t count the number of fish in the sea; you make projections of total biomass based on surveys and catch records. There were 191 million pounds of female fish big enough to spawn in 2023, well below the goal of 247 million.

Improving those numbers by changing different factors can seem like a guessing game.

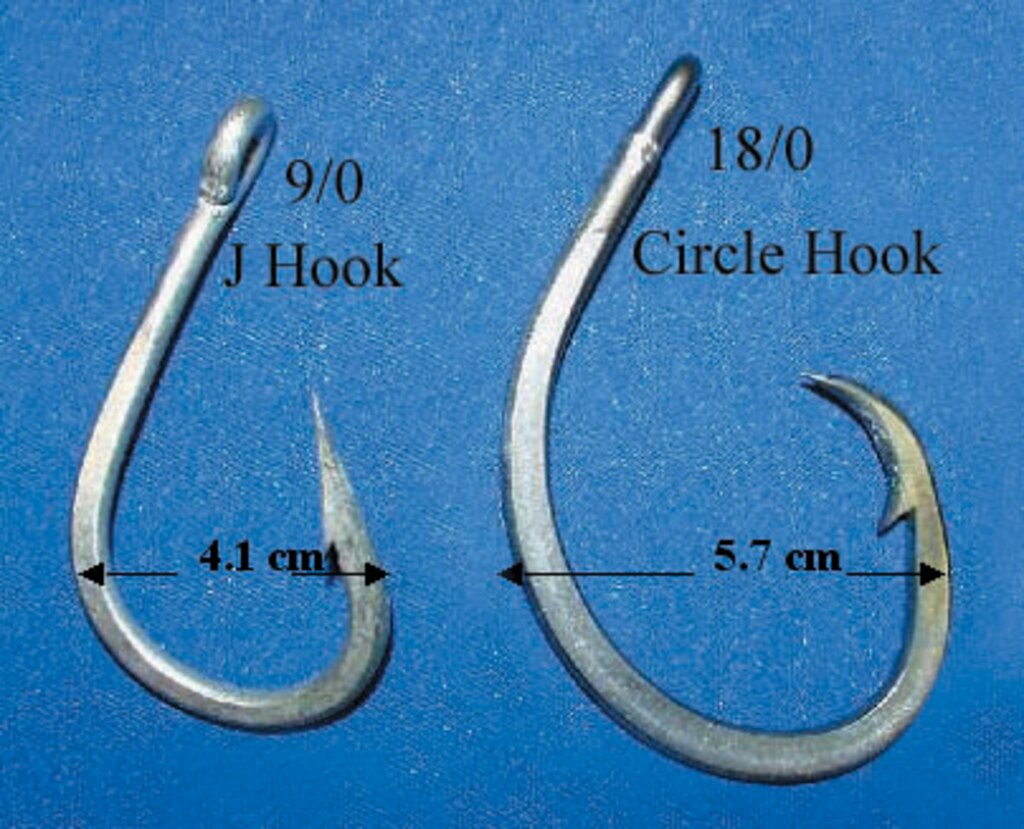

Some 40% of fish caught and released by recreational anglers die. Maryland and other states require the use of circle hooks, considered less likely than the traditional J hook to catch a rockfish by the belly and cause its death.

Only the science doesn’t show it’s working.

“Well, that’s disappointing,” one board member said.

Do you change the size limits for fish caught in the Atlantic? Or do you focus on the Chesapeake? If you reduce the number of days fishermen can target rockfish, will that be enough? Does it make more sense to protect big fish, little fish or something in between?

“When considering possible management response, the board should consider its risk tolerance and the level of risk the board is willing to accept as a management decision,” said Nelson, the rockfish scientist.

A December decision is a better risk than one made in February, the next regular board meeting.

Maryland’s 2025 rockfish season starts in March, and getting paperwork done, or redone, in time will be mindboggling for state regulators.

Until the board decides, everyone waits.

And the rockfish, ever a wily fish, gets a little harder to find.

“Everything is changing,” said Mason Hallock, who started charter fishing with his father and just bought the Bay Hunter II in Edgewater. “They’ve been showing up earlier than normal. Usually, they didn’t come to like June. They’ve been here since early May.

“We catch, you know, a few here, a few there, but they didn’t school like normally.”

Comments

Welcome to The Banner's subscriber-only commenting community. Please review our community guidelines.