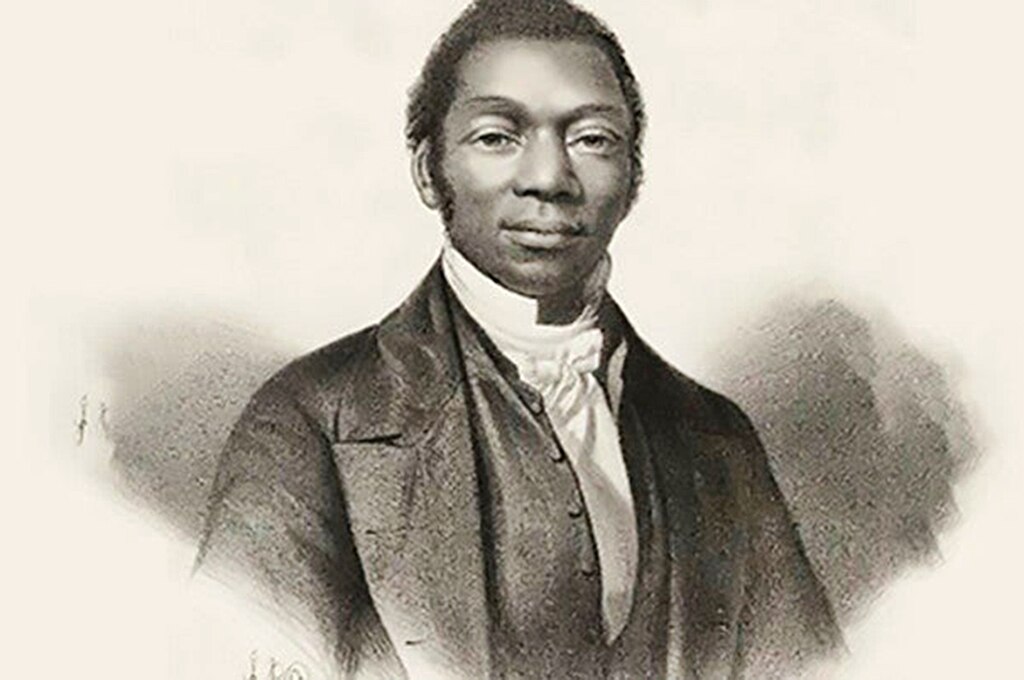

James W.C. Pennington began attending classes at Yale Divinity School in 1834, having escaped slavery in Maryland about seven years earlier. He was the first Black person accepted to study at Yale but was refused enrollment into the university and barred from speaking in class. He was never allowed to borrow books from the library while studying there from 1834 to 1837.

Last fall, nearly two centuries later, Yale conferred degrees on Rev. Pennington and Rev. Alexander Crummell, both Black men who studied theology at the university during the mid-19th century but were barred from formally registering as students or speaking in class.

In September 2023, Yale held events honoring the achievements of the two men, who became noted pastors, abolitionists and powerful advocates for racial justice. The university said it was seeking to atone for having failed to embrace them as students or treat them with dignity and decency.

“As the Reverend Pennington wrote, ‘it was considered intrusive’ — indeed illegal — for Black men like himself and the Reverend Alexander Crummell to matriculate, much less graduate, from Yale Divinity School, where they were regarded as ‘visitors,’ relegated to the back of the classroom, and required only to listen — never to speak,” Yale President Peter Salovey said in his remarks. “And so today, it falls on us to reckon with our history. It falls on us to rise to our responsibility and as a university we have begun to do so.”

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

Any such reckoning requires that we understand what lives such as Pennington’s reveal about this country and its institutions. It requires learning the true history of slavery and its intentional, systematic dehumanization of Black people. It means understanding how that dehumanization became a fundamental fact of life for Black Americans.

Efforts such as those at Yale constitute beginning steps that U.S. institutions must make to come to terms with their histories. Slavery and the slave trade were foundational to making America an economic power. U.S. corporations and banks profited from the exploitation of enslaved Black people for decades. Universities and other institutions financially benefited as slaveholders. In the decades after slavery, discrimination against Black Americans was carried out by the U.S. government, in every kind of institution and in every walk of life.

Some institutions in the U.S. and around the world are, at long last, beginning to take responsibility for policies and practices that did such great harm specifically to Black Americans. They are expressing some understanding that the harm didn’t end when those policies and practices were no longer in plain sight. The impact of slavery and discrimination has shaped the lives and prospects of Black Americans throughout all of American history, and the impact is still felt today.

Yale’s actions are among measures taken by U.S. universities to acknowledge how racism and slavery influenced their histories.

At Johns Hopkins University, the Hard Histories at Hopkins Project, launched in fall 2020, examines the role that racism and discrimination have played at Johns Hopkins. The project is intended as a frank and informed exploration of how racism has been permitted to persist as part of the university’s structure and practice.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

At the University of Maryland, the 1856 Project aims to investigate the university’s “connections to slavery in order to provide a blueprint for a richer understanding of generations of racialized trauma rooted in the university.” The university describes its work as “embarking on truth-telling projects that address human bondage and racism in institutional histories.”

Yale’s Divinity School renamed S100, one of its largest and busiest classrooms, in honor of Pennington, who was born Jim Pembroke in 1807. He was enslaved on the Maryland plantation of Frisby Tilghman, who lived with his family at his estate, known as Rockland, in Washington County. Tilghman was noted for his cruel treatment of the people he owned.

Pennington was affected greatly by the evil and immorality of slavery, particularly when he witnessed its horrors inflicted upon his father. Once, Pennington watched his master approach in a foul mood and beat his father savagely. Pennington said he was never the same after seeing his father cruelly and abjectly humiliated.

“Although it was sometime after this event before I took the decisive step, yet in my mind and spirit, I never was a slave after it,” he wrote in his autobiographical narrative, “The Fugitive Blacksmith,” which was published in 1849.

Pembroke escaped in 1828 at age 21, in an eight-day ordeal during which he was captured twice and escaped twice more. He found his way to the home of a Quaker family in Pennsylvania, where he began his education. He moved on to New York and then settled in Connecticut. He changed his name to Pennington and educated himself in Christian theology, becoming a Presbyterian minister dedicated to the abolition of slavery.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

In 1841, he wrote what is believed to be the first history of African Americans, “The Origin and History of the Colored People.”

Pennington used his autobiography to denounce slavery and condemn the “chattels principle,” under which people are listed as goods along with livestock and other assets of a household. He argued that enslavers couldn’t be true Christians because their willingness to buy and sell other human beings is contrary to the very foundations of Christianity.

“Talk not then about kind and Christian masters,” he wrote. “They are not masters of the system. The system is master of them.”

After his time at Yale, Pennington served in Newtown, Connecticut, where he performed the wedding ceremony for Frederick Douglass and his fiancée, Anna Murray. In Hartford, Pennington worked on the case of the Amistad captives and organized the first Black missionary society to support them on their return to Africa.

He spent the rest of his life fighting for the abolition of slavery and for the rights of freed slaves during Reconstruction. He died in Jacksonville, Florida, in 1870.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

The American odyssey of James W.C. Pennington exposes, in the starkest manner, an entire collection of big lies that are still being sold in public and political discourse.

No, enslaved people could never be treated well. They were enslaved. They were subject to every conceivable form of exploitation and brutality — including torture and murder. No, slavery wasn’t a vehicle for the enslaved to acquire skills that would prove beneficial to them. Slave labor was stolen labor. Skills enslaved people brought from Africa or that they acquired were used entirely to serve the interests of their enslavers.

Any assertion that the U.S. was never a racist country relies entirely on some sort of American mythology and on a white nationalist perspective. The denial of freedom and opportunities for Black Americans based on race has helped shape America’s entire history.

So now, with teaching of the history of Black Americans under attack, learning about Pennington and others like him takes on greater urgency. Moving toward any genuine reckoning or reconciliation regarding America’s history of Black enslavement, Jim Crow and discrimination will require truth-telling. That’s the only way we can understand the country’s real history and how that history led to the current racial hierarchy. Accountability starts there. The words of Yale’s president speak to that point.

America’s enslavers, its laws and its institutions were aligned to take away Pennington’s freedom, his humanity and his life. But instead of having his soul and ambitions crushed, he never gave up.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

One man’s life stands as an example of how will, perseverance, courage, faith and love could rise above the worst of America and its history.

Mark Williams is The Baltimore Banner’s Opinion Editor.

The Baltimore Banner welcomes opinion pieces and letters to the editor. Please send submissions to communityvoices@thebaltimorebanner.com or letters@thebaltimorebanner.com.

Comments

Welcome to The Banner's subscriber-only commenting community. Please review our community guidelines.