The Crown was the newest, hottest space in Central Baltimore, and word was spreading that it was looking to fill the void for artists who needed somewhere to congregate. The timing couldn’t have been better. That year, 2013, the beloved makeshift venue The Broom Factory Factory, better known as the BFF, in Remington had been shut down by the city under suspicious circumstances.

I was in my early 20s, juggling jobs as a teller at M&T Bank, an usher at the Charles Theater and an occasional contributor to the now-shuttered Baltimore City Paper. But this was my newest gig, co-hosting a new party series called Kahlon with my friend Abdu Ali, who was then an experimental, genre-bending rapper.

The two of us had a mission: to harness the magic of the city’s creative community filled with brilliant misfits and transplants who ended up in Baltimore by way of MICA, while also attracting young adults from the Black neighborhoods where we were raised. We figured, if we could do our part in fostering a cultural exchange, the potential for making something memorable was endless.

On Saturday night, Nov. 9, 2013, young people who typically packed Baltimore’s raggedy warehouse spaces that doubled as living quarters and DIY music venues convened outside on Charles Street between North Avenue and 20th Street. Kahlon was throwing its inaugural show with a lineup that featured Abdu, club music vocalist TT The Artist, ballroom dancer David Revlon and indie/electronic artists Ponyo and Gurl Crush.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

We packed the dance floor while people stomped, swayed and vogued until staff turned the lights on. After feeling the energy that night, we knew we had a duty to contribute to the city’s alternative ecosystem by making sure this could be a recurring event.

For the next four years, The Crown would be a sanctuary for Kahlon and our peer group, helping launch careers that spanned far beyond those doors, this city and even the country. More importantly, it provided a space for people to feel they were part of something important. Something that belonged to them when they were within those walls.

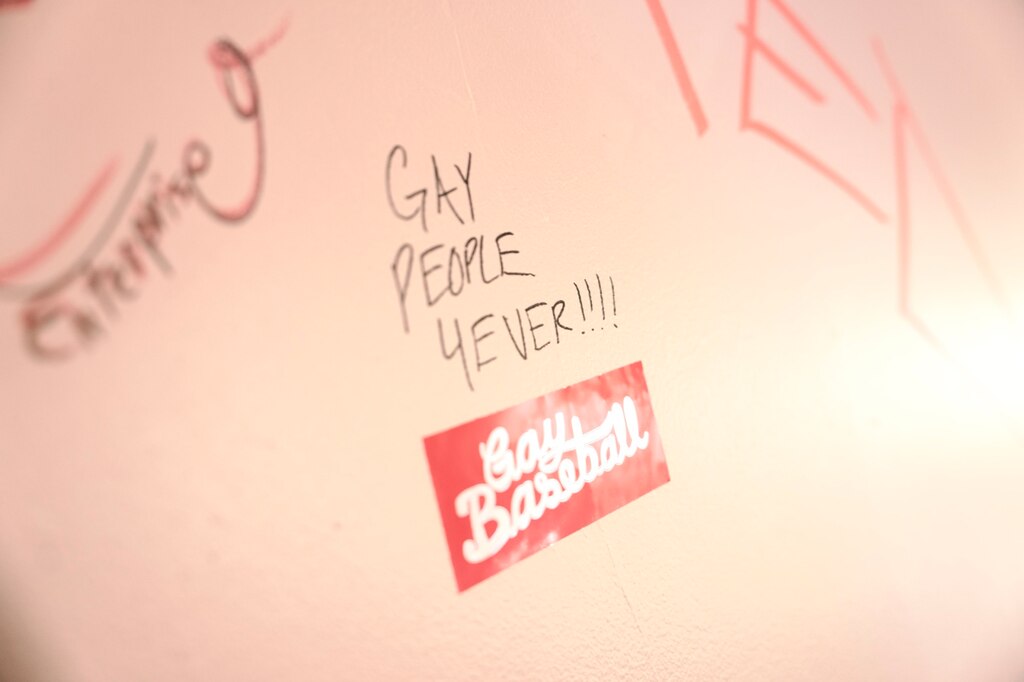

We forged a sense of community there. The head of security, Tony, turned into a celebrity from the hours of 10 p.m. to 2 a.m. The bathrooms, as deplorable as they were, became a famed canvas for partygoers to tag their names. The sidewalk out front of The Crown emerged as a destination in its own right, a place for people to hang out if they couldn’t get inside.

Even after we closed up shop on Kahlon, many others — most notably, 808s & Sadbois and Version — followed and made it their home. I relocated to New York City in 2016 but, when back in town, The Crown remained a crucial stop for me to stay in touch with what was bubbling in Baltimore, beyond what I could see on my phone screen.

Unfortunately, those days have come to an end. A few weeks ago, The Crown posted on its social platforms that Sunday would be its final day of operation, without much explanation. The local corners of my X and Instagram feeds spent the following days eulogizing the place, reliving long passed days of their less stressful youth, when the highlight of their week or month was heading down to Charles Street with enough funds to get into a party, get twisted on remarkably cheap cocktails, then get sustenance off of Korean bar food to save themselves from passing out.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

It wouldn’t be hyperbole to say this place changed the trajectory of my life. The same night we launched Kahlon, I debuted my zine, True Laurels, which documented the scene we were giving a platform to in the form of interviews, album reviews, photo essays and artist diaries. In the interest of ensuring the outside world was aware of, and interested in, what Baltimore had going on, I wore the hats of a journalist, a party host and an all-around advocate. Without that level of participation, I’m not sure what kind of life or career I would have today. The Crown provided a home base for me to contextualize the ever-evolving nature of the musical landscape here.

In the early to mid-2010s, Baltimore’s music was undergoing an important cultural shift. Instead of spreading its gospel through local radio play and high school parties as it did during my adolescence in the 2000s, Baltimore Club was adapting to the social media age and the EDM boom in which producers from around the world were incorporating elements of our homegrown genre into a more sanitized, commercially viable sound. To stay on trend, local producers including Matic808, Rip Knoxx, Mighty Mark and DJ Dizzy took cues from this transition and, in the process, ushered in a new generation of club. Abdu Ali and TT The Artist established a branch off the club music tree that centered the queer nightlife experience, borrowing elements from ballroom to signal both worlds.

The rap ecosystem here was changing, too. Lor Scoota and Young Moose borrowed from Chicago drill artists and started to broadcast the raw realities of the city’s most deprived areas, making themselves cultlike figures who could quickly reach audiences outside of the city. And then there was the alternative spectrum of the rap game: the late OG Dutchmaster, Butch Dawson and, eventually, JPEGMAFIA, now one of the world’s biggest alt-rap artists.

As a young journalist, I diligently covered this creative boom and The Crown gave me a place to document this wave — not just with words but in a physical expression through curated Kahlon shows. My work about, and at, The Crown developed me into a resource to national publications who wanted on-the-ground reporting on intriguing, lesser-known scenes. Eventually, I was hired by those New York-based publications to cover the wider music world, along with Baltimore music for a larger audience.

What I’ll miss most about that time is the exhilaration of early adulthood, of world building, the assurance that your vision and ideals are reflected in a community. Young creatives, more than anything, need to be told yes to their ideas, not inundated with hindsight-driven advice. The Crown told me and Abdu yes when we wanted to make it Kahlon’s permanent home. And, at its critical height, the party was featured on an episode of VICE’s “The Great Adventures of The Kid Mero” in April 2014. The Crown told me yes when I wanted to start my own rap-focused party called Flat Out that brought artists from all around to perform. And The Crown told others with lofty ideas yes when they didn’t feel quite at home anywhere else. For all those green lights, I’m thankful.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

But The Crown’s power isn’t necessarily in the physical place. It’s in the experiences, the opportunities to grow and evolve, the ability to relay stories from those times to serve as inspiration to new generations as they carve out their own spaces.

Baltimore will persist and evolve, and has already started doing so even before The Crown officially announced its closure. The Royal Blue — walking distance from 1910 N. Charles Street — with its disco ball-adorned dance floor, packed parties and solid bar food — had already essentially replaced The Crown’s position in Central Baltimore. Life-altering experiences for people in their 20s will be created there, just as they were created elsewhere for me. And someday, when it ceases to exist, something else will take its place. The cycle is infinite.

In the midst of this perpetual change, it’s important to pause, meditate and honor the moments that leave a lasting impression. The Crown did that for me. And, while it felt as if it might exist forever, I’m grateful for that little window of time.

Comments

Welcome to The Banner's subscriber-only commenting community. Please review our community guidelines.