A crowd of more than 500 people gathered before nightfall Sunday evening, their heads bent for an opening prayer at Memorial Baptist Church. They were urged to contemplate Baltimore City’s vacant housing crisis as they prepared to hear the details of a plan to work on ending it.

The Rev. Cristina Paglinauan, of The Church of the Redeemer, asked the crowd to envision residents of Fulton Avenue and Preston Street walking to buy groceries, young kids playing in recreation centers, and residents using park benches, all enjoying a lively neighborhood without a vacant building in sight.

The gathering represented a first step forward for a newly formed coalition of local government, faith and business leaders who say they will use their collective heft to address Baltimore’s vacant housing crisis. The city lists just under 14,000 homes as vacant or abandoned, the latest data shows, and the complexities of remediating the problem have confounded government leaders for decades due to the expense and legal hurdles.

Now, Mayor Brandon Scott, Greater Baltimore Committee President and CEO Mark Anthony Thomas and representatives of BUILD Baltimore — an interfaith community organization — say the time is right for a private-public partnership to form a united front focused on finding solutions.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

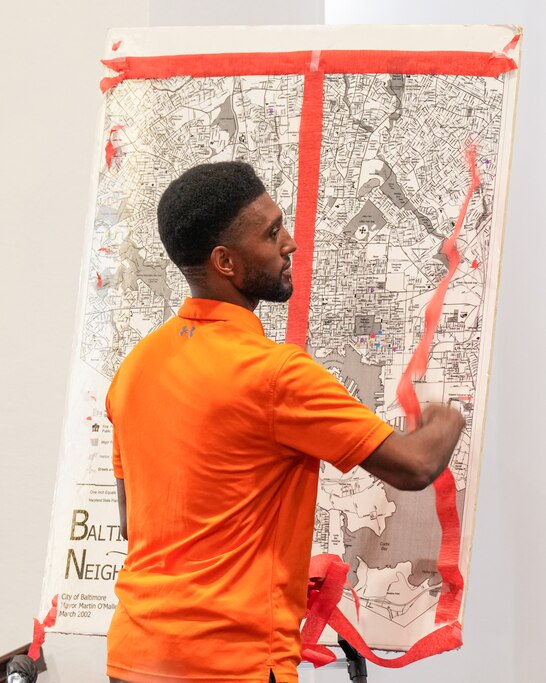

Red ribbons adorned rows of pews in the church, meant to symbolize the extensive redlining that first began in Baltimore — with banks refusing loans to Black homebuyers — and became a model of discrimination across the country. Throughout the night, attendees were encouraged to rip the bows.

“Redlining was born in Baltimore,” Scott said, “but it will also die here.”

The mayor joined members of the BUILD coalition for a similar gathering about six months ago, when the group said a $7.5 billion investment would be needed for vacant house remediation. Then, in May, Thomas, the new head of the city’s Greater Baltimore Committee, unveiled plans to tackle the problem, too. The group said Sunday that it has formed an official steering committee, with one member from each entity, to help oversee an implementation plan that would shed light on the strategies ahead of the 2024 legislative session in Annapolis.

The renewed push signals a show of solidarity among the group, which has not united on a single issue in more than 30 years, members of the coalition said. Starting in the 1980s, the cohort helped craft and implement plans for what is now the CollegeBound Foundation, a Baltimore institution that helps city students “to and through” college education. Scott is an alumnus of the CollegeBound program.

The group aims to fund two studies to be completed as early as the fall: one focused on the bureaucratic and policy challenges associated with eliminating vacant houses, and the second on financing such a feat. Members of the group said as much as $2.5 billion of the $7.5 billion would have to come from public coffers.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

But they also emphasized the need for change.

“Kids are more familiar with the smell of burning vacants than they are with a blooming rose,” said the Rev. George Hopkins, a BUILD Clergy co-chair.

City officials already have spent years, and millions of dollars, focused on blight remediation. In March 2022, a few weeks after a vacant house fire killed three city firefighters, Scott committed $39 million in federal COVID-19 relief funds to support building and bulldozing, upgrades to the city’s permitting system, housing enhancements for legacy residents, and more pathways for renters to become homeowners. And millions have been allocated for projects in specific neighborhoods, called Impact Investment Areas, where rehabilitation work is ongoing.

Meanwhile, BUILD and its partners at REBUILD Metro, a nonprofit development organization, have spent years remediating blight block by block in three East Baltimore neighborhoods: Johnston Square, Oliver and Broadway East. There, they say, homicide rates and housing vacancy rates have plummeted.

“We’ve invested $200 million in East Baltimore and cut vacancies by 85%,” said the Rev. Dr. Calvin Keene, pastor at Memorial Baptist. “The murder rate has been cut in half.”

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

But housing experts and researchers say piecemeal, and even block-by-block investments, aren’t enough. A study published last year by the Johns Hopkins University’s 21st Century Cities Initiative found that Baltimore loses $100 million in tax revenue from vacant properties every year and spends another $100 million annually on maintenance. Meanwhile, the homes tend to be concentrated in the city’s predominantly Black neighborhoods, exacerbating long-standing problems in those communities and keeping some at a competitive disadvantage.

”In neighborhoods with more vacant housing, there are more crime risks and more health disparities,” said Bishop Dr. Kevin Daniels, the pastor at St. Martin Church of Christ. “We have to get this done for our children and our seniors, our neighbors in Brooklyn, [on] Pennsylvania Avenue and North Avenue.”

Members of BUILD and the GBC say they can devote more attention to the problem than a busy city government likely can and can help fundraise toward their goal. Still, members of the group said they also know they can expect hurdles along the way, including assuring potential investors that they can work quickly enough.

At the end of the gathering, the Rev. Paglinauan presented the mayor and Thomas with a gift, a framed photograph of a double rainbow that she saw on her way home from a previous meeting on vacant housing.

“As you walk out of the church tonight, look at the houses across the street” the Rev. Dr. Keene said. “... See the people who are working to make people’s lives better.”

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

Comments

Welcome to The Banner's subscriber-only commenting community. Please review our community guidelines.