Legionella bacteria has been found in more government buildings in Baltimore, prompting officials to plan to flush and sanitize the water systems at two courthouses this weekend.

Tests on the water systems at the District Court buildings at 5800 Wabash Ave. in Northwest Baltimore and 700 E. Patapsco Ave. in South Baltimore that were done on Nov. 25 returned positive for Legionella bacteria on Wednesday, state officials confirmed on Thursday.

Legionella bacteria can cause Legionnaire’s disease, a serious form of pneumonia. People are exposed to the bacteria when they breathe in vapor or mist from water that contains the bacteria.

The discovery comes after office buildings at the State Center complex tested positive for Legionella bacteria and are now being flushed and sanitized. A total of six buildings — including offices and courthouses — have now tested positive.

The two courthouses, where judges hear cases ranging from traffic violations to civil disputes, will remain open for business this week, according to the state Department of General Services, which maintains the buildings.

The courthouses also house offices for probation agents, prosecutors and public defenders.

They’ll be closed on Saturday and Sunday so the water can be shut off for the sanitizing process. The buildings will reopen on Monday, though it will take up to two weeks for testing to determine whether the Legionella bacteria is still present.

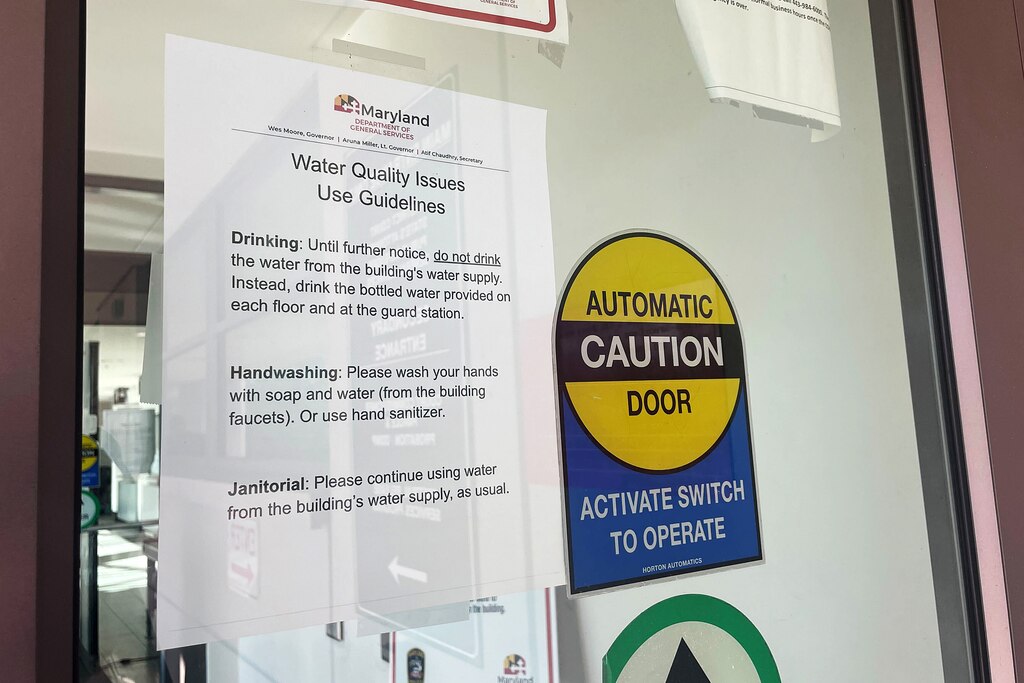

At the South Baltimore courthouse, water fountains were covered in black plastic and signs were posted on the front door, at water fountains and in bathrooms, cautioning visitors not to drink the water due to “water quality issues.” The signs did not mention the discovery of Legionella bacteria, though a notice on the website for Baltimore City courts does mention the bacteria.

Maryland Public Defender Natasha Dartigue said in a statement that “in an abundance of caution,” employees have been offered alternative work site options.

The Office of the Public Defender “will continue to monitor the situation closely, adhere to guidance provided from MDH and adapt policies to protect employees while continuing to do the important work of serving clients and the community,” her statement said.

Department of General Services spokesman Eric Solomon said Thursday that the state began proactively testing for Legionella bacteria in state buildings in mid-October. The goal, Solomon said, was to “establish baseline testing and best practices to monitor water quality in its buildings across the state.”

State Center was the first location to be tested, and the bacteria was found in two buildings there on Nov. 8, prompting a brief closure. Two more buildings later tested positive.

The state is in the midst of closing four State Center buildings one by one to flush and sanitize the water systems. It will take up to two weeks for testing to determine if the bacteria has been flushed out.

Two unions representing employees at State Center have raised concerns that the state did not communicate well with workers. They’ve questioned whether it’s safe for employees to be in the buildings.

“Employees are receiving updates about maintenance, building closures and precautionary water use parameters via memos that are circulated on a regular basis,” Solomon wrote in an email. “Employees have also been advised to report any symptoms of pneumonia and to contact a healthcare provider to help determine the cause.”

There have been no reported cases of Legionnaire’s disease associated with the state buildings, according to Solomon.

State Center employees have been directed to work from home when their building is closed, and upon return, they are being provided bottled water and urged to wash their hands and use sanitizer.

These are all proper steps, from the initial testing to the follow-up and notices to employees, said Natalie Exum, an assistant professor at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health’s Department of Environmental Health and Engineering.

She said the threat is low for most workers and visitors to the building, but she said not to play down the real concern for those who are older, smokers and those with compromised immune systems.

Exum said there was no requirement that building managers do the testing, and there are likely many other older city buildings with complex water systems that are harboring the Legionella bacteria. That means if people get sick, they may not suspect the Legionella bacteria, which is treated with antibiotics.

The threat level depends on how many samples in a building tested positive and at what levels, she said, adding, “Just having the bacteria doesn’t necessarily correlate to danger.”

One fountain with low levels is easier to clean than a hot water heater, for example. Also, people typically only become infected when they breathe aerosolized bacteria into their lungs, like during a shower rather than drinking from a fountain. The bottle water handed out by state officials is largely to protect workers from debris or cleaners that end up in the system when it’s flushed.

She said state officials should ensure they are not only taking the proper steps to identify and address the bacteria, but also communicating with workers about their concerns. More buildings should be testing, she said.

“This is the type of proactive water management that should be going on in large buildings with complex water systems,” Exum said. “And it highlights the importance of continuing to monitor. People in your building could be at risk but you only know when you take water samples. Workers going back to these buildings should feel they are being protected by the facilities manager.”

Baltimore Banner reporters Meredith Cohn, Lee O. Sanderlin and Dylan Segelbaum contributed to this story.

Comments

Welcome to The Banner's subscriber-only commenting community. Please review our community guidelines.