In 1992, as the finishing touches of Camden Yards were in the works, Hall of Famer Frank Robinson, a former Orioles player, spoke with The New York Times about a critical piece of the equation.

Robinson — then an assistant general manager in Baltimore — pointed out the asymmetrical dimensions of the ballpark and noted that “we have the chance to put the triple back into the game.”

“It’s a fair ballpark,” Robinson said. “For a player, it makes a lot of difference going into a park and feeling comfortable. Not worrying, if I’m a pitcher, about whether the walls are too close, or wondering, if I’m a batter, ‘Can I hit one out?’”

Maybe Robinson’s perspective as a hitter clouded his ability to see it from the other side. Over the years, Camden Yards developed a reputation as a hitter-friendly bandbox. Just ask the pitchers.

When Mike Mussina was coming up in the early 1990s, there were still older, more spacious ballparks in use, including the old Yankee Stadium and Tiger Stadium.

“It was challenging at times. I’ll admit, it was challenging,” the Hall of Famer said in a 2017 interview with the Mid-Atlantic Sports Network. “The ball flew in the summer. You get those warmer summer months, and the ball flew out pretty good. But our guys got to hit here, too. So we floated a few balls out, too.”

Read More

After he was sent to the Orioles in a deal ahead of the 2017 trade deadline, starting pitcher Jeremy Hellickson said he was never a fan of the place.

“I think that had to do more with the offense I was going to have to face than the park, but it’s definitely not a pitcher’s park,” he told WJZ. “I definitely agree that a lot of guys don’t like pitching here.”

John Means was counting his blessings that he was in the Pacific Northwest when Mariners outfielder Kyle Lewis hit a deep shot in the eighth inning with the potential to end his no-hit bid in 2021.

“If this was Camden Yards, it was gone. I’m glad we’re in Seattle,” said Means, who successfully completed the team’s first solo no-hitter since 1969 and was nearly perfect.

From 1992 to 2022, no stadium saw more home runs than Camden Yards (5,911). But the downtown ballpark is now the ninth oldest in baseball, a testament to the wave of new stadiums it inspired. When the A’s open the 2025 season at Sutter Health Park in Sacramento, California, it will become the eighth oldest.

Still, the home run totals from recent seasons tell the tale of the tape. In 2019, the first season after Mike Elias took over as general manager, Camden Yards was second in home runs in Major League Baseball. The ranking dropped to 10th a year later during the COVID-shortened 2020 season, when the Orioles played just 33 home games, but jumped to first place in 2021.

The left-field wall, especially, proved too close for comfort for pitchers.

So the Orioles did something about it.

The baseball operations department evaluated data and determined it should move the fence back almost 30 feet in places, while raising the height of the wall, ahead of the 2022 season. And, in the last three seasons, Baltimore discovered it had “overcorrected,” Elias said in mid-November.

What had been one of the most hitter-friendly parks flipped to a pitcher-friendly haven. Right-handed hitters experienced the most issues with the wall. Statcast, MLB’s advanced analytics site, rated the home run park factor for righties at 79 from 2022 to 2024, the fourth lowest among major league parks. The home run metric had been a major league-high 125 from 2019 to 2021 for right-handed batters, suggesting it was 25% above average.

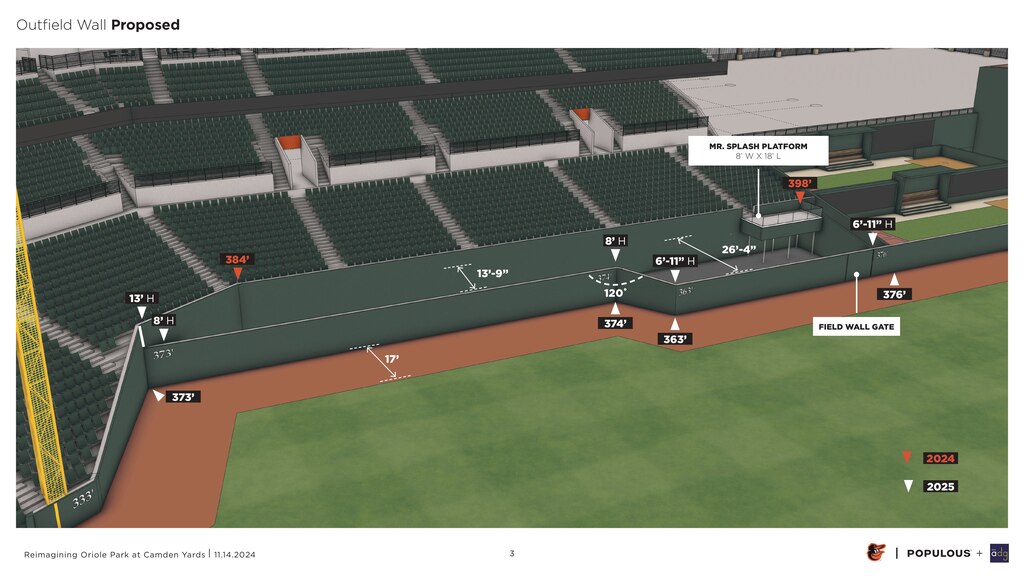

With an understanding that the pendulum swung too far in the other direction, the wall will come back in for the 2025 season. Not all the way to its original distance but to what could be a happy medium.

The wall will be up to 26 feet closer to home plate in some spots but about 9 feet closer in others. Its height will change, too — in left field, it’ll be 5 feet shorter, while in left-center, it’ll be just over 6 feet shorter.

The Orioles declined to provide specifics on how they decided on the new measurements, but using publicly available Statcast data, The Banner analyzed the factors at play and how the new distance could meet Elias’ aim of “a neutral playing environment that assists a balanced style of play at a park that was overly homer-friendly prior to our changes in 2022.”

The deeper wall in Baltimore — nicknamed “Walltimore” by some for how imposing it is — served pitchers well. It saved Orioles hurlers from surrendering an additional 65 homers, according to Statcast. But it also stole 72 homers from Baltimore’s batters.

That was the point, of course — the Orioles wanted to cut down on the number of cheap-shot homers to left field and thus make their organization a more attractive place for free agent pitchers. But, from the beginning, Elias didn’t treat the left-field wall renovation as a permanent one.

“Is it perfect? Is it the exact perfect dimensions? Does it look perfect? Is it going to stay that way forever?” Elias said at the 2023 end-of-season press conference. “No, and I don’t know. But we’re going to be renovating the stadium through this new agreement in the next few years.”

Three seasons after the initial change, Baltimore is amending the measurements now that there’s data showing how much the stadium favored pitchers. So how many of those long fly balls would be home runs in this new setup? Using Statcast, we can get a rough idea.

In straightaway left field, a large section of the wall is going from 384 feet to about 374 feet. And in left-center it’s coming in even further, going from 398 feet, where “Walltimore” meets the bullpens, to 376 feet. From 2022 to 2024, there were 91 balls put in play in left field that traveled 375 feet or farther where the outcome was something other than a home run — hit, out, error, sacrifice fly and so on.

Those balls would now clear the fence in most places. Had the proposed left-field wall been in place over the last three seasons, the number of home runs taken away by “Walltimore” would potentially drop from 137 to 46. But even that doesn’t paint the complete picture.

In left-center field, the wall juts in to 363 feet in one spot, inviting even more dingers.

Ryan Mountcastle could have had eight additional home runs, based on the data. Outfielder Austin Hays, catcher Adley Rutschman and outfielder Anthony Santander might have had four extra homers each.

In that way, Camden Yards could see a slightly more friendly left field for right-handed hitters, but it won’t revert to the extreme homer-friendly dimensions of old.

Colton Cowser studied the new dimensions of Camden Yards’ left field on his phone while talking on a Zoom call recently. The change is important for him, not so much as a hitter but because he primarily patrols left field in Baltimore.

Part of what made Cowser a finalist for American League Rookie of the Year was his defense. He has the range required to play center field, and with ample room to cover in left field at Camden Yards, that range served him well.

Now, although he might like the shorter wall from a hitting perspective — his opposite-field power as a lefty might be rewarded — the new dimensions will offer a new challenge on defense.

“Since it is going to be shorter in the left-center gap, you’re going to have to be more aware of some of the little quirks and corners going back to your left, rather than going back to your left previously was like, go as fast as you can that way and you’ll get to it,” Cowser said. “Now you have to be more aware of the wall.

“It’ll be interesting. There’s definitely going to be less room, so you’ll play a little shallower. But, also, dead left is still really deep, so you’re going to have to still cover that as well. … I’m picturing kind of where I’m going to be standing, and it’s almost to my right is deeper but to my left is shallower.”

Cowser will learn those quirks by playing there. The batters may be relieved when a deep fly ball does leave the yard. The pitchers might have a few more long balls on their record.

It’s another change. But it’s a change to a happy medium — or so the Orioles hope.

Comments

Welcome to The Banner's subscriber-only commenting community. Please review our community guidelines.