The question is a simple one: What can’t Kyle Hamilton do? The people who know him best cannot tell you much. It is not a long list.

Jackie Hamilton, his mother: “This is really hard because, again, he was one of those kids that, whatever he did, he was naturally good at it. Ummm, I’m going to have to get back to you on that. He can’t be perfect at everything, but …” (She sighs, almost contentedly. She does not get back to you on that.)

Conor Ratigan, a college teammate and close friend: “Ummm ... man, what is he not good at? I’m trying to think what we did that he’s not good at. I don’t — gosh, this is killing me, because if I can’t come up with an answer, that’s going to not help him here.” (He does not come up with an answer.)

Dan Perez, a football coach at Hamilton’s high school and former baseball coach: “If there was a weakness in his athletic prowess, he wasn’t the smoothest swinger of the bat, I’ll say that.” (Funny, because baseball was Hamilton’s best sport as a kid, until he gave it up out of boredom.)

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

Doug Jackson, a longtime family friend: “Despite how smart he is, Kyle has never been able to figure out tipping.” (Surprising, considering he can recite the first few dozen digits of pi.)

Hamilton’s stumped, too. At the end of a recent week of practice, the Ravens’ second-year star fastens his gaze in concentration as the locker room empties. Five seconds of silence pass, then 10. “I’m trying to think,” he reassures a reporter. Finally, eureka.

Read More

“Diving,” Hamilton deadpans. “I could never get diving. It took me, like, a whole summer. It took me a whole summer to learn how to dive off the diving board.”

Of course he has the answer. In a season of revelations for the Ravens’ elite defense, Hamilton’s meteoric ascent has been the most consequential — and perhaps the least surprising. The former first-round pick is, quite literally, built differently, upending the modern prototype for NFL safeties with a generational blend of talents: a physique that inspires comparisons to NBA lottery picks, a dedication to film study that rubs off on family members, a versatility that lends itself to “unicorn” comparisons, and an “uber intelligence” that optimizes his every move.

This was the hope when the Ravens made Hamilton one of the highest-drafted safeties in recent history last year. Afterward, he’d called his surprising fall to No. 14 overall a “blessing.” Only now is the rest of the NFL realizing what was truly possible with Hamilton: everything.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

“I told you that he was going to be a Pro Bowl-type of player,” Ravens pass game coordinator and secondary coach Chris Hewitt says. “He does everything. He covers, he blitzes, he tackles. There’s nothing that kid can’t do.”

The challenge has always been figuring out what more Hamilton can do. From there, he usually figures it out himself.

‘The best athlete I’ve ever seen’

At 13 months, Hamilton was already turning into a ball hawk. He had just started walking around the family’s home in Italy — where Kyle’s father, Derrek, a former third-round pick of the New Jersey Nets, was playing basketball professionally — when, his mother remembers, one ball rolled out of his grasp.

It settled under a windowsill with a marble ledge that jutted out somewhat. Hamilton went after the ball. It was a tight squeeze; he was too tall to just walk under the ledge. So he ducked his head and grabbed the ball. What happened next has stuck with Jackie.

“Most kids — a toddler — would just stand up, right?” she says. But Hamilton avoided bonking his head. “He grabbed the ball and he kind of backed out to clear the ledge and then stood up.” It was as if Hamilton instinctively understood where to be, how to move, his brain and body in precocious harmony.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

“I mean, that’s minor, but for a 13-, 14-month-old, I’m like, ‘That’s clever,’” Jackie recalls. “That’s him understanding his surroundings and being aware.”

As Hamilton grew up, his talents flowered. Things seemed to come naturally to him, Hamilton’s upbringing nurturing his sense of what was possible. His dad’s basketball career had exposed him to athletic outliers. His brother, Tyler, was 4 years older and a gifted athlete and student himself. His mother was artistically inclined and keen on indulging her sons’ “curious minds” — and sharpening them, too.

“Again, I am Korean,” Jackie says, chuckling at the memories of their extracurricular workbook assignments in various school subjects. “I’m one of those parents.”

Jackie recognized the athletic potential of her children. (Tyler would go on to play college basketball at Penn and William & Mary.) But she “didn’t want them to be just complete jocks.” When they settled in Atlanta, she would take Kyle and Tyler to the High Museum of Art, to the Center for Puppetry Arts, to Zoo Atlanta. At home, they’d make finger paintings and other arts and crafts.

A couple of Kyle’s pieces won prizes at his school. Another was picked for exhibition at a local art museum. A drawing he completed in the second grade, of a spider and a sprawling spiderweb, still hangs in Jackie’s home.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

“It just came naturally to him, and to be honest, I’m kind of saddened that he kind of stopped as he got older,” Jackie says. “The arts and crafts are not as cool when you’re older.”

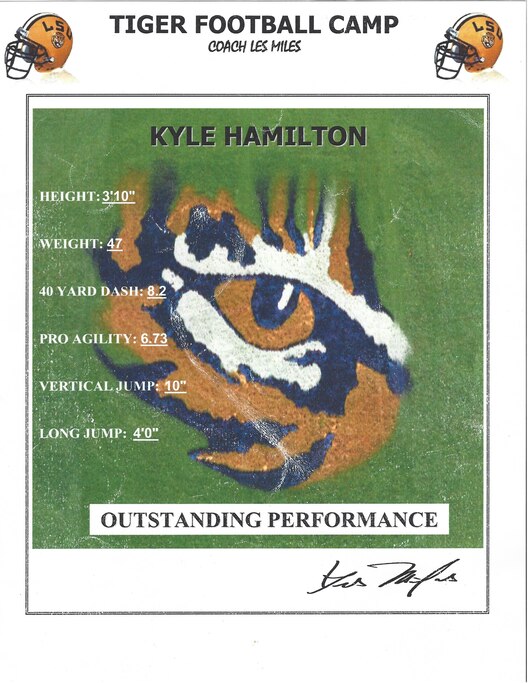

Atlanta’s fields and courts were fast becoming Hamilton’s canvas. As a 5-year-old, an age at which tee-ball teammates were doing dirt angels in the outfield and chasing butterflies, he completed his first of two triple plays. At an LSU football summer camp, where Hamilton was competing with kids at least a few grades up, his athletic testing — 8.2-second 40-yard dash, 10-inch vertical leap, 4-foot long jump — earned an Outstanding Performance certificate.

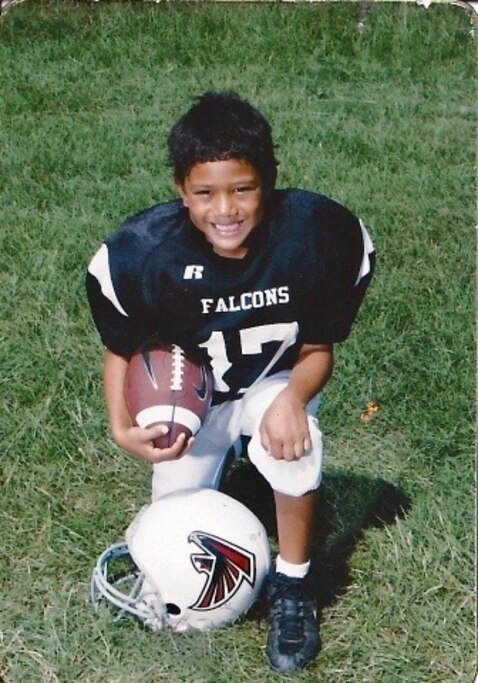

Jackson, the family friend who coached Hamilton and his own son, Nick, now a standout linebacker at Iowa, in youth football, called him “one of the most naturally gifted athletes that I’ve ever seen.” Hamilton was of the smaller kids on his team, with an “Itty-Bitty” nickname to match, but one of the hardest hitters. “He’d blow ’em up,” Jackson says.

As an eighth grader at Marist School, a private Catholic school in the Atlanta suburbs, Hamilton was playing touch football one day in Perez’s physical education class. Sean McVay had starred at the school over a decade earlier, but Marist was not a blue-chip football factory. Hamilton stood out. No one could touch him.

After the class ended, Perez, an assistant on the football team, remembers walking into head coach Alan Chadwick’s office. “Coach, I just saw the best athlete I’ve ever seen at this school.”

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

Where? “In my PE class.”

Really? Who is it? “It’s this kid named Kyle Hamilton.”

Getting past the ‘brick wall’

During the predraft process last year, Hamilton took a test called the Athletic Intelligence Quotient. Developed by psychologists Scott Goldman and Jim Bowman, the 35-minute exam was, in some respects, a repudiation of the Wonderlic test, which measured cognitive ability but had no correlation with on-field performance. The AIQ, crucially, did not draw on acquired knowledge; instead, it assessed attributes such as pattern recognition, decision-making ability and information retrieval.

Goldman, who’s worked as an embedded team psychologist in the NFL, had come to believe that four “buckets” determined an athletic profile: physical ability (Are they big, strong and fast?), personality (What’s their work ethic? How do they fit in the locker room?), experience (How long have they been competing?) and intelligence.

The challenge was understanding and then quantifying athletic intelligence. As they formulated their tests, Goldman and Bowman asked coaches and front-office officials across the NFL about the cognitive abilities that mattered most at each position. “What are the tasks that you really need?” Goldman remembers asking.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

“Sometimes coaches look for players to run through brick walls,” he says. “But the reality is that what coaches really want is, they just want to get them to the other side of the wall. So I think people who are concrete thinkers” — those who use reasoning based on how they experience the physical world — “all they can do is run through brick walls and therefore oftentimes are more tolerant to discomfort, because that’s what they have to do.

“People with a higher level of intelligence, they can find creative ways and solutions to get around the brick wall. And isn’t that what we really want anyways?”

Hamilton’s AIQ test results, which he agreed to disclose to The Baltimore Banner, were exceptional. He had “superior” scores in visual retention, spatial awareness and manipulation rotation, an attribute measuring how he might adapt to his changing visual field as a play unfolds.

Hamilton, who in the third or fourth grade had tested into the high-IQ society Mensa, also had no weaknesses, the testing showed.

“Intelligence is one of the greatest predictors of success, and that’s across domains — lawyers, firefighters, police officers, airline pilots,” Goldman says. “And I think the reason for that is, people with high levels of intelligence, they can do a few things that just help them navigate life. … When shit’s not working, they can scrap the plan and say, ‘OK, that’s not working. Let’s come up with something else.’ And you’ve got to think that’s just a huge, huge advantage in life.”

A natural talent

Especially in poker. Ratigan, a former Notre Dame wide receiver who roomed with Hamilton, was in a low-stakes league at the school with friends. When Hamilton found out about the games, he wanted to know more.

They hadn’t lived together for long, and Ratigan was just beginning to grasp the extent of Hamilton’s aptitude for, well, anything. Ratigan had considered himself pretty good at the popular “NCAA Football” video game — until he started playing Hamilton on their Xbox 360. Then he started losing. “Well, that’s a little frustrating,” he remembers thinking.

Ratigan invited Hamilton to the poker league anyway. Then Hamilton started winning. Again.

“And everyone kind of got sick of that,” Ratigan says. “He goes from not really playing much to walking away with all the money, and all these guys are getting mad at me, like, ‘So are you sharing in the profits with this guy? Is this, like, a team thing?’”

Ratigan didn’t know how to explain it. “He just kind of picked up on how everyone played pretty early on, more so than others did.”

Adaptability is Hamilton’s superpower. He was raised to understand not only the inevitability of mistakes but also the lessons they offered. “The difference from somebody who succeeds and somebody who may not,” his mother says, “is whether you can learn from it and make adjustments for your future.” Hewitt, the Ravens’ assistant coach, says Hamilton rarely makes the same mistake twice.

When Kyle was in school, Jackie says she would’ve liked him to have studied “a little harder.” She also knows he didn’t really need to. The natural talents Kyle had as a kid, he honed. The abilities he lacked, he learned.

Public speaking? “Good at it,” Hamilton says. “I think the more notoriety you get, the more reps you get at speaking publicly, and you get naturally better at it.”

Math? “Up and down. Depends what kind of math. Like, trigonometry, I was terrible at it. I was good at algebra and geometry.”

His recall? “I know a good amount of pi,” and he rattles off the first 41 digits of the mathematical constant without error, as if he’s reading them off a graphing calculator.

Golf? “Yes and no. I feel like starting young with that sport is definitely a plus, because it’s not a natural movement, really. Guys who play baseball, they’re further behind because they’re just always hacking at it. But, um, no, I feel like I picked it up pretty quickly.”

Freestyle rap? “I would say I’m actually very good at freestyling. It’s going to be explicit, but I’m pretty good at it.”

As his mother explains: “Whatever he does, he does it better than most.”

A defensive ‘unicorn’

Hamilton doesn’t mean to brag. This, those close to him say, is just his confidence in his competence. Even Hamilton’s most fantastical notions — that he, a former NCAA Division I basketball recruit, could score on Victor Wembanyama, the San Antonio Spurs’ 7-foot-4 rookie star — are rooted in pragmatism. (Hamilton’s one-on-one strategy: Drive by the No. 1 overall pick and protect the ball by going up for a reverse layup, or bury Wembanyama deep enough in the paint that he can attempt a dunk.)

With Hamilton, there is value in believing anything is possible. As a rookie, he went viral on X (formerly Twitter) after losing badly in a one-on-one training camp repetition against undrafted wide receiver Bailey Gaither, who’s never played an NFL snap. “[I] am getting fried on this app,” Hamilton joked afterward. When the season kicked off, his role fluctuated. He didn’t play more than half of the Ravens’ defensive snaps in a game until Week 8.

Now Hamilton, who leads all AFC strong safeties in Pro Bowl voting, might be the most indispensable member of one of the NFL’s best defenses. With him on the field this season, according to TruMedia, the Ravens have led the league in yards per play allowed (4.3) and ranked second in success rate (63.9%). With him off the field, the Ravens have ranked last in yards per play allowed (6.1) and last in success rate (52.2%).

“We always joke about the one clip he went viral for,” says safety Geno Stone, a close friend. “And he always jokes about it, too, because he’s like, you know, ‘It’s one-on-one.’ You’re going to lose your one-on-one reps, especially in a practice like that. They can run [routes] wherever they want. But it is funny because everyone tried to write him off then, and now he’s, I would say, one of the best safeties in the NFL.”

Partly because he does more than any safety in the NFL. Perez likens Hamilton to a Swiss Army knife; general manager Eric DeCosta has compared him to a “unicorn.” At points this season, he’s morphed into an explosive edge rusher, a shutdown slot cornerback, even a surprise inside linebacker.

At 6-4 and 220 pounds, with a lean, leggy frame that Cleveland Browns coach Kevin Stefanski likened to Wembanyama’s, Hamilton has become a skeleton key in Mike Macdonald’s defense, unlocking not only schemes but also his own untapped potential. His ever-changing skill set, coach John Harbaugh says, is a “gold nugget,” enriching the defense with every evolution.

In coverage, Stone equates one Hamilton stride to “three steps for everyone else.” As a pass rusher, Odafe Oweh marvels at how Hamilton seemingly mastered a spin move in training camp just one play after asking the outside linebacker for tips. Cornerback Marlon Humphrey jokes that, “if you cloned 11 of him, he could play every single position.”

“It speaks to his intelligence and his ability to pick all those different schemes up and not hesitate,” says Chadwick, his high school coach, who had to rebuild Marist’s playbook to better feature Hamilton’s talents — on offense. “He can analyze information. He can retain it, and that’s invaluable, because they do so many things, so many schemes and fronts and coverages and all that. It’s difficult. And, when you have somebody like that, it shows how they use him.”

Added Jackson, his former youth coach: “He really does live at this intersection of marrying uber intelligence with uber athleticism. That’s unique. And Kyle’s a very cerebral athlete. He’s smart as hell.”

And, the Ravens hope, only getting smarter. When Jackie visits Kyle in Baltimore, he likes to turn his film study into a mother-son bonding activity. “You want to learn something?” Hamilton will ask, and he’ll show her his iPad, explaining how, say, an offensive lineman’s presnap posture is hinting at a run play.

“I’m actually learning,” Jackie says. “I understand football. I’m a football girl. I love it, and I understand it.”

As the AFC-leading Ravens prepared Wednesday for their Christmas Day showdown against the NFC-leading San Francisco 49ers, a possible Super Bowl preview, Hamilton was asked about the showers of praise he’d received this season: Did it mean anything? The acclaim was “cool,” Hamilton acknowledged. He’d always dreamed of NFL success, and he felt he’d done “pretty well” so far.

“But I feel like I hold myself to a high standard,” Hamilton said, “and I have a lot more getting better to do.”

Comments

Welcome to The Banner's subscriber-only commenting community. Please review our community guidelines.