When developers built our Towson neighborhood in the late 1920s, they named the streets for Southern states and refused to sell to Jewish families.

On Sunday night, though, for the first time anyone can remember, we lit the menorah at the annual Christmas party. Three Jewish families recited the Hebrew blessings for the candles. I explained to the small crowd of onlookers in Santa hats that the holiday celebrates the miracle of a small band of Jewish fighters triumphing over antisemitism to have the right to practice their religion. Santa was due to make rounds on the fire truck, so I hurried through the explanation of the miracle that the holy temple’s oil lasted for eight days instead of just one. We passed out some chocolate gelt coins, spun a dreidel, and pressed “power” on what is forevermore our electric neighborhood menorah.

What took so long to include Jewish neighbors in the holiday celebration? Why now? And how is it possible for a suburb like Baltimore County to have one of the largest Jewish populations in the United States even though it once had encouraged neighborhoods that forbade Jewish residents?

I’ve lived in Southland Hills since 2006. I’ve served on the improvement association’s board, produced its newsletter, and helped with the website. I’ve interviewed some of the oldest neighbors, now no longer with us, and cherished their anecdotes about the days when Towson University was a small teachers’ college and much of the neighborhood was undeveloped fields.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

Our association dues cover the cost of communal parties, among them the annual Christmas party and an Easter egg roll. I rarely attend these; I don’t necessarily mind my dues going to those events, but they never seemed for me or my family.

Nazis killed many of my mother’s relatives, and we grew up not wanting to draw attention to our Jewishness outside of our tight community. I never wore a Jewish star, nor asked for my religion to be included at work holiday parties. My mother — without success — begged my Latin teacher not to make me sing “O Come, All Ye Faithful.” We didn’t want others’ holidays forced on us, but we didn’t want to be included, either. We just wanted to be left alone to our Chinese food and our movies.

It never occurred to me to ask that Jewish traditions be included in the neighborhood festivities. Nor did it occur to the handful of other Jewish residents. Some were raised secular, some married non-Jewish spouses, and some may have felt as I did — that religion was more of a private observance.

But a younger Jewish mother moved into the neighborhood during the COVID-19 pandemic, and she pointed out that the community party this year fell on the first night of Hanukkah. Could we do something? A board member reached out to me. Quickly, a quartet of Jewish mothers got on a text chain with him and made some quick decisions. We’d go with an electric menorah, so we could use it regardless of wind. We’d have gelt, dreidels, and jelly doughnut holes. We’d squeeze the menorah lighting in right before Santa for maximum attendance. And so it was done. In a year when antisemitism in the United States is soaring, a neighborhood built on discriminatory principles came together to celebrate its Jews.

That brings us to the third answer. The Baltimore area includes almost 50,000 Jewish households, according to a 2020 Jewish Community survey by Brandeis University. Most live in the Pikesville and Owings Mills areas, their families having migrated decades ago from the city. Nearly half of the population was raised here, with long-standing ties to the community. They have tended to settle close to family, following the migration patterns set out a century ago.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

In 1910, Baltimore became the first city to legislate segregation, forbidding Black families from living in desirable areas and relegating Black citizens to fetid, crowded slums. The courts ultimately struck that down, but city leaders found other ways to keep residents segregated. Redlining on maps showed where Black families could procure loans and insurance.

Prohibitions on Jewish families were less obvious, but “Hebrews” were unwelcome in the garden suburbs that Baltimore was famously developing. The first of these was Roland Park, the second Guilford. Both enforced covenants that barred Jewish families from buying homes, going so far as to check that prospective buyers were not coming from Jewish areas and that they were referred only by upstanding Christian community members.

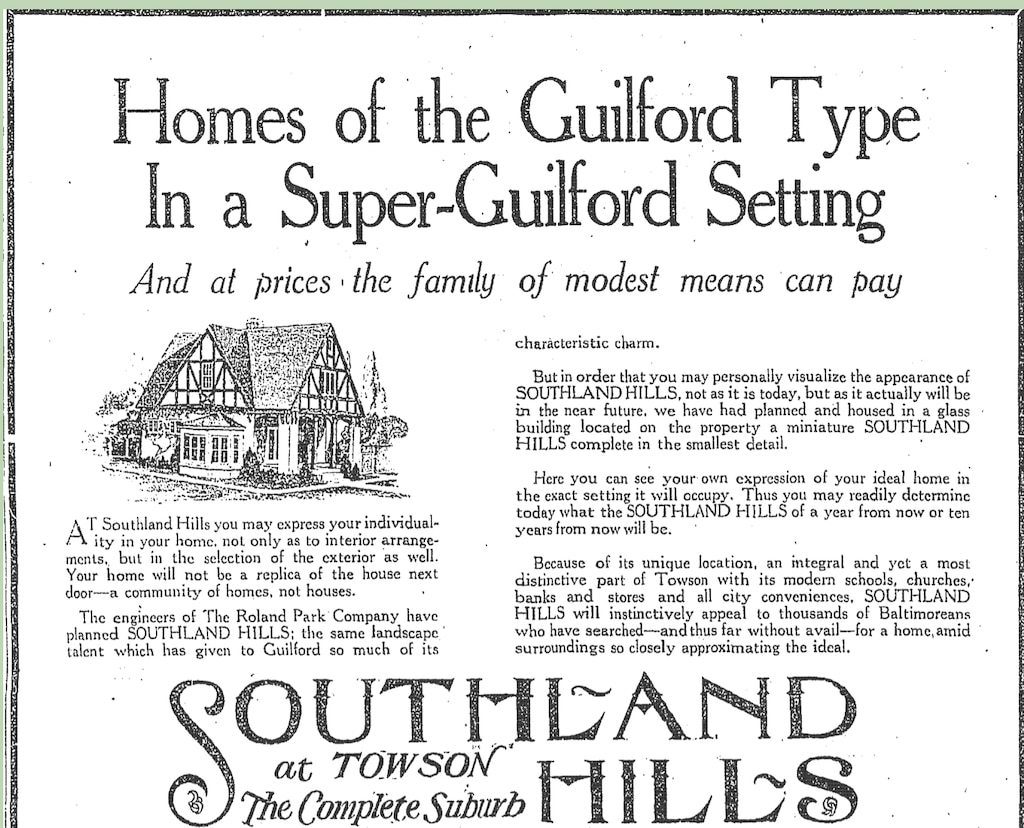

Southland Hills was the third of these garden suburbs. Unlike Meadowbrook Swim Club, which put out a sign declaring only “approved gentiles” could swim there, The Southland Co. used more genteel messaging. Brochures described the “suburb complete” as “a restricted community of the Guilford type.” Perhaps not seeing the irony, another ad described “a well restricted home development where the family of discrimination will find the ideal environment.”

Developers named the streets for Southern states, with Dixie Drive as the neighborhood’s spine and Colonial Court one of its borders. It was a time when much of the nation was nostalgic for a time they didn’t actually remember, with Confederate monuments erected throughout the South and funds flowing in to restore plantations that once relied on the labor of enslaved people. The discriminatory covenants helped fit the aesthetic.

Did I notice the Southern theme when we bought the house? I did, but at the time I didn’t fully grasp the history. My husband and I were so taken with a quiet neighborhood that was walking distance to a gym, restaurants, and a bagel shop that we didn’t think too much about what had come before us.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

In 1948, the courts struck down restrictive covenants. But as with Brown vs. Board of Education, it would be another decade or two before all the counties got the memo. And Baltimore County was notoriously segregationist, with the U.S Civil Rights Commission describing it as a “white noose” around the city. The Jewish population of Baltimore made inroads into Lutherville, but its presence in Towson was limited until more recently.

Unlike our community’s founders, the people who live here today did not come because of restricted covenants catering to their “discriminating” tastes. They are the best neighbors anyone could ask for — caring, compassionate and kind. As antisemitism reaches levels not seen in decades, they showed up for their Jewish neighbors, and promised to do it every year. They helped me realize that I don’t want to be left alone — I only wanted someone to invite me to the party.

On Hanukkah, they taught me that the light comes in from unexpected places, but it does eventually shine.

Rona Kobell, a Baltimore journalist who has covered the Chesapeake Bay for years, is editor-in-chief of the Environmental Justice Journalism Initiative.

Comments

Welcome to The Banner's subscriber-only commenting community. Please review our community guidelines.