In the 19th century, a clandestine network of Baltimore County churches, residences and farms served as stops on the Underground Railroad, offering shelter and sanctuary for escaped enslaved people on their journey to freedom. Yet much of this history remains overlooked.

A 170-year-old Windsor Mill congregation wants to change that.

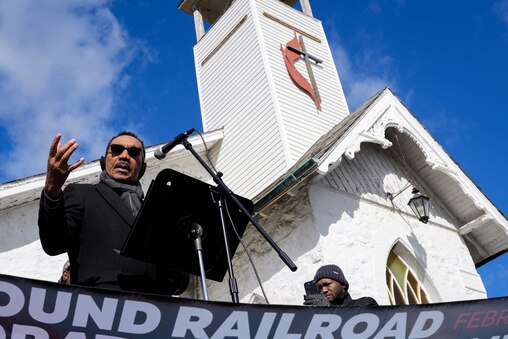

To mark the beginning of Black History Month, the Emmarts United Methodist Church recently celebrated its legacy as a former Underground Railroad safe house. Around 200 people, many from predominantly Black West Side communities, sang freedom hymns, cheered a dance troupe’s performance and heard presentations on the church’s role in resisting slavery.

“There is a sacredness to the ground you stand on,” U.S. Rep. Kweisi Mfume told the crowd with the church’s towering belfry in the background. “People ran and walked and crawled across these grounds in the middle of the night to get to a sanctuary and be able, the next day, to go out and seek freedom.”

In Maryland, it’s common to associate the Underground Railroad with Harriet Tubman’s heroic efforts on the Eastern Shore. But wherever slavery proliferated, there were attempts to escape it. That includes Baltimore County, where the enslaved population averaged around 6,500 in the early 1800s, accounting for 20 to 30% of its total population. There were thousands more in the city of Baltimore and Anne Arundel, Carroll, Harford and Howard counties.

Read More

Within Baltimore County, enslaved people experienced brutal conditions, including grueling labor, family separations, beatings and whippings. Many fled for Pennsylvania, just over the county line, or the city, where there was a large community of free Black people.

The stories of those dangerous journeys along the Underground Railroad have received little publicity. Some at the Emmarts Church celebration on Feb. 1 were learning about its legacy as a safe house for the first time.

“I’ve driven past, but I didn’t know,” said Debbie Scruggs, 55, of Owings Mills.

Scruggs noted that it was especially meaningful to be at the church during such a fraught political moment, when many conservatives are pushing back against the teaching of racial history.

“Right now, we need some history. They’re trying to fight us from learning history.”

Historians have encountered challenges uncovering the locations of Underground Railroad safe houses, which operated in secret and left behind few written records about where escaped slaves stayed or who offered them assistance. Much of the history survives through oral accounts that are harder to verify, and as a result many aren’t formally recognized.

The National Park Service’s Network to Freedom program identifies more than 800 locations across the country with connections to the Underground Railroad. Neither of the two in Baltimore County are safe houses.

One, Hampton National Historic Site in Towson, was among Maryland’s largest plantations. It enslaved more than 500 people and had a well-documented history of escapes. The other marks a site on York Road where local slaveholders convened in 1851 on their way to pursuing escaped enslaved people in Christiana, Pennsylvania. There, they encountered an armed resistance that some regard as the start of the Civil War.

Emmarts Church, at the corner of Dogwood and Rolling roads, began piecing together its past with the help of local Black historians, including Louis Diggs, who spent three decades researching and collecting oral histories. Diggs, who died in 2022, identified at least seven Underground Railroad safe houses in Baltimore County, including Emmarts.

Still, it took several more years for the church to share its history. Many within its congregation were unaware.

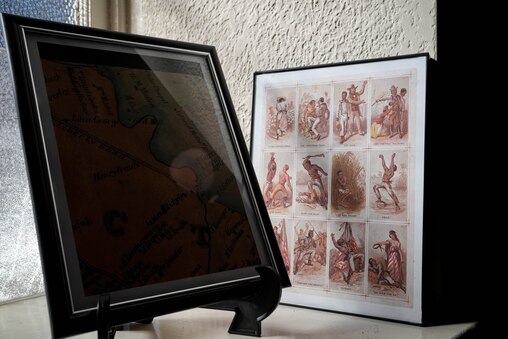

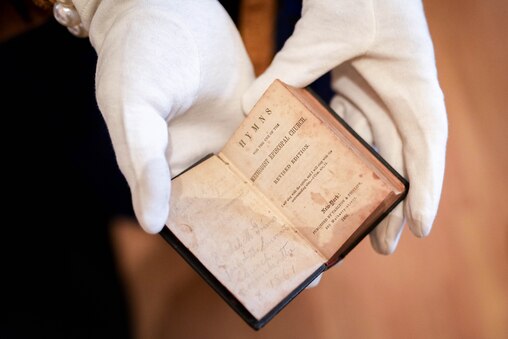

Christine Hughes, a church administrator and 25-year member, said she began unearthing artifacts in the building’s basement around six months ago. They included minutes from the church’s 1855 founding, photographs of its founders and old blueprints.

“You kind of put things together,” said Hughes. “It was powerful to know that you’re walking on ground that’s really important, and that people literally put their lives on the line for somebody they didn’t necessarily know.”

The church bears the names of Caleb and Susannah Emmart, who, according to Diggs, also hid escaped enslaved people in their two-room house across the street.

The Emmarts’ former residence was relocated to a site off Liberty Road, where it still stands. Its current owners are a septuagenarian couple, Jeff and Shirley Supik, who purchased the home in 1980, not knowing at first of its historical significance. Their efforts to help preserve it led the county to declare the Emmart-Pierpont Safe House a historic site.

“This is the kind of history we need to embrace,” Shirley Supik said. “To know that those people [who traveled the Underground Railroad] were that tenacious, they were that strong, they were that courageous — we should all know that story.”

The celebration of Emmarts Church began with a symbolic walk up Rolling Road. There are a couple of theories on how the West Side thoroughfare got its name, but both connect to the slavery era. One suggests it stems from the Emmarts’ brother-in-law, Nicholas Smith, a cooper who hid escaped enslaved people in his barrels and rolled them towards freedom. Another links it to enslaved people who rolled hogsheads of tobacco to the Patapsco River for shipment.

Baltimore County Council Chair Mike Ertel said the walk helped him imagine what freedom seekers must have experienced and how they viewed the church as a place of refuge. He then issued a citation honoring Emmarts as “a historic symbol of African American resilience and freedom.”

The church has struggled in recent years. About half its members died during the coronavirus pandemic, pastor Isaiah Redd said, while others left for other places of worship. The congregation has never fully recovered and is now down to about 20 active members; many are elderly.

“I didn’t give us another two years to stay open,” Redd said.

He and other leaders hope that sharing Emmarts’ history will rekindle its connection to the community and breathe new life into the congregation.

“We want to keep the memory of why this church was built alive,” Redd said.

Comments

Welcome to The Banner's subscriber-only commenting community. Please review our community guidelines.