Even on air, WBAL television reporter Rob Roblin could be silly.

When reporting on “The Love Boat,” a Valentine’s Day cruise, he brought along his wife, telling viewers that there was “romance in the air.” The camera cut to a shot of a closed door, and his wife could be heard saying said she was not going anywhere with him with his “stupid hat” and “stupid shirt.”

“Come on!” he said, opening the door. He was wearing an extravagant printed shirt with a matching fedora. He made eye contact with the camera.

“Oops,” he said on the archived video.

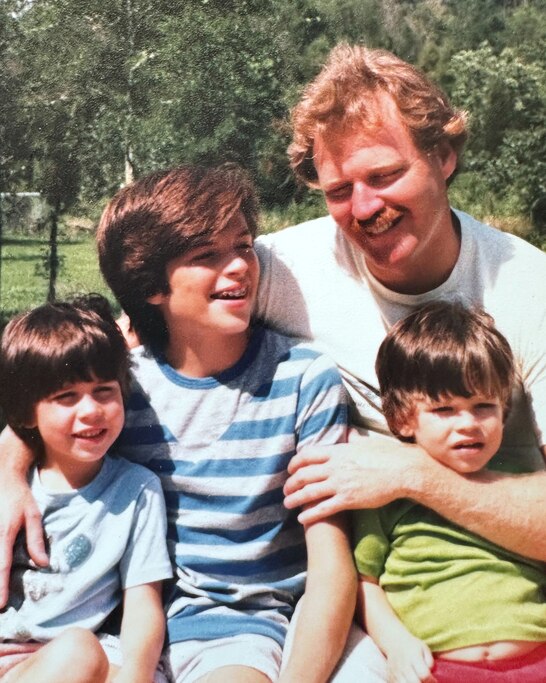

What Baltimoreans saw on television was what his children got at home, said Stephen Roblin, his youngest son.

Rob Roblin didn’t shy away from getting emotional in his last address at WBAL after 40 total years in local television news, his son said. He thinks it was why his father was a skilled storyteller— he made sure people knew how he felt. And people responded to it.

Read More

Rob Roblin died of a stroke earlier this week at the University of Maryland St. Joseph Medical Center. He was 79.

A tenured anchor known on TV Hill as “Robbie,” he approached his coverage with humor, even as he braved intense winds, lashing rain and pelting sand while delivering “unforgettable” and “iconic” hurricane coverage. Ron Kershaw, the station’s news director at the time, hired him in the early 1970s.

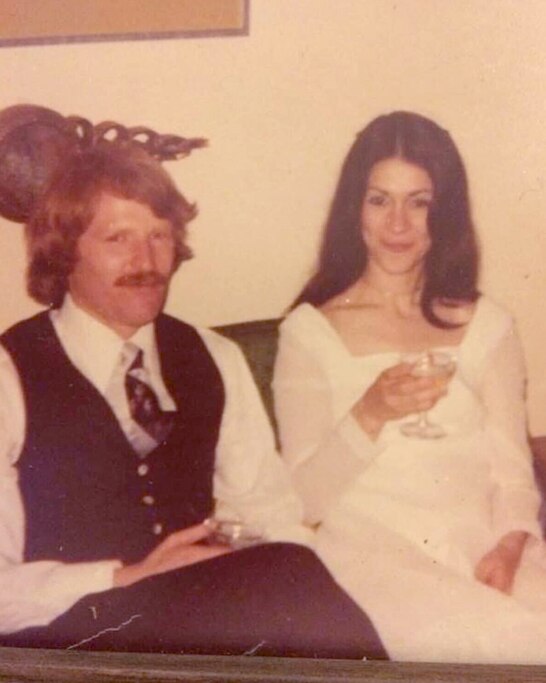

Robbie moved to Baltimore for a job as a cub reporter from Mississippi. He did not plan to stay or to fall in love.

Yet he just got Baltimore, his elder son Ablan Roblin said.

Hearst Corporation would hire Robbie five times, with stints in Alabama, Florida, San Francisco and Chicago. But no matter what market he explored, he kept coming back to Baltimore. In his last rehire at WBAL, he stayed for 24 consecutive years, retiring in 2014.

“I think WBAL recognized something in him that he didn’t see himself, to be honest,” Stephen said. “They saw him as a great storyteller.”

“Humor and heart”

Robbie was as heartfelt as he appeared to be on television, and funnier, too, Stephen said.

“On television, you got the PG version,” Stephen said. “At home, you got the R-rated version.”

He declined to tell his dad’s more risqué jokes, but he remembers one of the sillier ones. Stephen walked in the kitchen for breakfast one morning. His dad greeted him with a hug and a kiss.

“I love you, baby,” his dad said. “Have a banana. Do you know what Beethoven’s favorite fruit was?”

He paused. Then he raised his voice dramatically, emphasizing each syllable a bit louder to the rhythm of the first few notes of the 5th Symphony: “Ba, na, na.”

Ablan said his father’s jokes were quick, though hard to miss.

“Humor and heart,” Ablan said, “are the things he led with.”

That is how he approached reporting, too. Robbie told his sons more than once that Baltimore is a city where there is “a whole lot of heart,” and he felt a deep sense of obligation to report on this rawness with dignity and honesty.

Baltimore got a lot of negative news coverage — and Robbie understood why, never one to romanticize the past. But he saw a need in balancing things out, making sure people saw the good in the city, too.

He knew there was a story in Herman Johnson, a basketball coach in Bentalou Rec Council, a recreation center in West Baltimore. He knew he needed to highlight the Special Olympics, jumping in the frigid waters of the Chesapeake Bay for the Polar Plunge.

Then he took what he learned home to parent his children. He took Stephen to play basketball in West Baltimore with Johnson.

“The world is a lot bigger than where you grow up, and you need to know that, and you need to be able to interact with people from all walks of life,” he told Stephen.

And Robbie could talk, his youngest son said. Strangers would recognize the television reporter when the family went out on weekends, and Robbie engaged with them, asking questions, often ending the conversation with a hug.

“I reflect back and feel fortunate that I was able to see the impact of his work,” Stephen said. “Because I don’t think he fully appreciated it at all.”

“I never will meet someone like him again”

Beau Kershaw described his father as a difficult but successful man who had a lot of loyal people working for him. One of them was Robbie, who cared deeply about family— and he had a loose definition for family.

Robbie had dinner with Beau on Fridays when the reporter flew off to Chicago to do freelance reporting before going back to his family in Alabama. Robbie took Beau in for a year after his father died of cancer.

Beau remembers waking up in the couch with Robbie’s two younger kids looking at him.

“I never will meet someone like him again,” Beau said. “That’s why I miss him so.”

Robbie had also lost people at a young age. His mom died when he was in elementary or middle school, Stephen said, and his dad when he was in high school. Robbie lost his brother when he was a young adult.

He never thought he was going to live long, something he talked about openly, his youngest son said.

The journalist felt lucky and fortunate most days of his life— lucky that he had sons he was proud of, that they all found partners they loved, that he got to see them grow up and have kids of their own.

Those grandchildren became his entire world after he retired.

His three sons gave him six grandchildren, and he considered Beau’s two kids his grandchildren too, Beau said. The youngest was named after Robbie.

The Banner publishes news stories about people who have recently died in Maryland. If your loved one has passed and you would like to inquire about an obituary, please contact obituary@thebaltimorebanner.com. If you are interested in placing a paid death notice, please contact groupsales@thebaltimorebanner.comor visit this website.

Comments

Welcome to The Banner's subscriber-only commenting community. Please review our community guidelines.