This group of Remington residents has a list of grievances and worries that is long and varied. Gathered across the street from the site of Johns Hopkins’ planned Data Science and Artificial Intelligence Institute, a handful stood in a semicircle on a recent summer evening and rattled them off.

The construction is loud, and the workers can be rude. Some of them litter and take residents’ parking. Tall, leafy oaks that have lined the street for decades are set to be cut down. Storm runoff from an existing construction site is flowing into Stony Run. More is sure to follow.

“It’s like this frog in boiling water,” said Amy Horst, who lives on the 3100 block of Remington Avenue, across the street from campus. “You start to get normalized to the trash, the noise. You’re like, ‘Oh, it’s not that bad.’ And the next thing your house is gone like that.

“It might sound outrageous to say right now, but I think that we’ve all come to understand there is no stopping” Hopkins.

If those concerns sound like hyperbole, understand both Hopkins and its neighbors have outsize expectations. Nothing like it has been built before.

The university has presented the Data Science and Artificial Intelligence Institute, or DSAI, as a transformational opportunity for Hopkins and Baltimore. It could turn the city into an East Coast tech hub and make it synonymous with artificial intelligence.

The center could fuel solutions to mankind’s most intractable problems in medicine, science, education and other fields.

The plan is to build two buildings on the edge of the Homewood campus, near the intersection of Wyman Park Drive and Remington Avenue.

Hopkins officials predict the construction, which will take about four years, will generate 11,000 jobs and $1.6 billion in economic impact. Once completed, the structures will have more combined square footage than CFG Bank Arena. DSAI is supposed to employ 140 new faculty and researchers, and attract 750 doctoral students. It will be the largest institute of its kind.

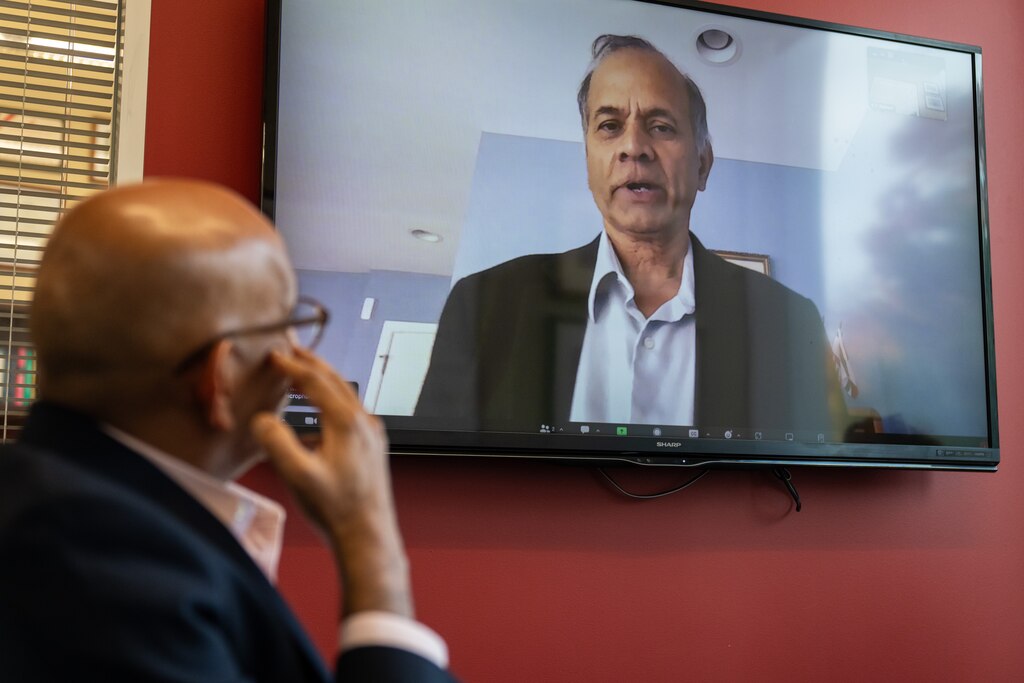

“AI will be the lifting tide that will lift everything in and around Hopkins,” Rama Chellappa, the interim director of DSAI, said. The effects of DSAI on the city are expected to be so widespread that Chellappa joked Baltimore should rename the Inner Harbor as “AI Harbor.”

“What would it take for that to happen?” he said.

But what may be a boon for the city has become another bitter chapter in a long-running saga between Hopkins and its neighbors.

Before DSAI, it was the fight over the creation of Hopkins’ police force. Before the police, it was concerns of students snapping up the local housing and disrupting neighborhoods such as Charles Village.

Johns Hopkins seems to hold them in disdain, the neighbors say, and there are worries Hopkins, with the help of the city and state, will snap up property for redevelopment and displace residents, as it did in East Baltimore decades ago.

There’s always been something, and each time Hopkins has come out on top, to the point that a sense of inevitability has taken hold.

“They will just do whatever they want,” Councilwoman Odette Ramos said of Hopkins in an interview last month.

Last summer, Ramos, whose district includes the Homewood campus, sent a letter to university leadership seeking $100 million in community investments in exchange for her to ditch a proposed zoning change that could have hampered DSAI’s development.

Whispers soon started that Ramos had tried to shake down Hopkins. Good government groups and the director of the city’s ethics board said that was not the case, but the perception lingered.

Although Ramos said she would approach future negotiations with a different tack — none of her demands was met — the exchange illustrates the extent to which some Baltimoreans feel the scales are tipped in Hopkins’ favor and how powerless they are to change it. Ramos said she sent the letter, in part, as a way to show her constituents she would stick up for them.

“I needed to ... make sure that Hopkins knew that they can’t just roll over communities, because that’s what they did in the EBDI. That’s what they’ve done in other places,” she said.

The DSAI project is not on the same level as East Baltimore Development Inc., which involved the displacement of hundreds of Black families near the Johns Hopkins University medical campus. The DSAI buildings are being erected on land the university already owns, and only campus buildings will be torn down. The project does not require special zoning variances, and no extra tax breaks have been provided.

Still, what transpired with the EBDI has shaken people. Today, Remington Avenue is a line of modest rowhomes, a mix of homeowners and renters. An influx of new faculty and students who work in lucrative technology fields means the area could become more expensive and crowded.

“My concern is my home is not going to be my home in 10 years,” said Dylan Maddox, a real estate agent whose family has lived on this block since 2001.

Maddox and her neighbors’ homes are the lone barrier between this side of Hopkins’ campus and Wyman Park. Other residents posited that one day Hopkins could try to buy their homes, taking a piecemeal approach until it owned all of the land on both sides of the avenue.

Hopkins officials said it was not in the university’s current plans to acquire those properties. Although the construction will be a nuisance, the result should make for a net positive, said Beth Blauer, Hopkins’ vice president of public impact initiatives. Blauer, who lives near campus, said she bought her home in the area because it would retain value and encouraged people to keep a holistic view of Hopkins and the DSAI project.

“Change is hard in any community,” Blauer said. “But the reality is there are lots of people across our city who have had their lives changed because of employment at Hopkins. Their children are first generation going to college because of Hopkins. We have people that are getting lots of benefit from not just being affiliated with the institution but living in the city that the institution is deeply committed to.”

Prophecies of doom aside, the neighborhood’s immediate concerns are largely environmental. At the end of the block is Stony Run, a tributary to the Jones Falls, which flows into the Chesapeake Bay. The city spent millions to rehabilitate the peaceful creek and ravine, which is a sort of oasis within the city.

In a recent video posted to the Instagram account “bmoreagainstdsai,” a torrent of storm runoff from a different construction site — the Agora Building — next to the DSAI location could be seen flowing downhill and into Stony Run. That video received tens of thousands of views and, a day after it was posted, Hopkins erected a fence around the construction site to better control the runoff.

University officials said the change was made after a city inspection, but neighborhood residents feel it was a response to their public pressure campaign.

“We shouldn’t have to do that, constantly, to get them to actually keep their promises to the neighborhood,” said Hillary Gonzalez, an informal leader of the neighborhood’s opposition and a self-described naturalist who manages the “bmoreagainstdsai” Instagram account.

The Friends of Stony Run, a volunteer group that acts as a sort of river keeper, recently met with Hopkins, and its president Glenn Carey said he came away “encouraged” by the university’s updated plans to prevent environmental harm. But it will remain engaged in “providing due diligence and oversight” throughout the construction.

There is also the issue of the trees. The DSAI plan requires 102, including 30 in the public right of way, to be cut down.

Hopkins plans to plant 300 trees as part of the DSAI construction, with all replacement trees in the public right of way being at least 25 feet tall.

Residents say the construction workers themselves have become something of a neighborhood nuisance. Instead of parking where Hopkins directs them to, they take up residents’ street parking. And they can be rude, locals allege.

Jessica Hudson lives on the corner of Remington Avenue and Wyman Park Drive — her house is the one with the giant mural of an orange tabby cat on the side — and has had unpleasant run-ins with workers recently. She confronted one worker in early August who, Hudson said, placed an empty cup on her fence instead of throwing it away.

“I told him, ‘Hey, that’s my yard. Don’t litter. Throw that away properly.’ He got pissed off and he said some choice words, and then tossed it on this front lawn, which is park property,’” Hudson said while standing outside her house, which shares a border with Wyman Park.

Hopkins has held 14 meetings about its DSAI project with community members, all in an effort to address or alleviate their concerns. There’s a website that is supposed to provide updates on construction progress every two weeks — Gonzalez, who checks it regularly, said the site is not maintained as often as it should be. Residents regularly email Hopkins administrators with complaints and, according to emails shared with The Banner, are often met with silence.

The neighborhood may not be able to do anything to stop or even alter Hopkins’ DSAI plans — the city’s planning commission keeps approving the university’s designs.

But even saving one of the nine soaring scarlet oaks slated to make way for a construction entrance on Remington Avenue would be a victory. Gonzalez, standing under the canopy, likened the neighborhood’s plight to the Old Testament underdog tale of David and Goliath.

“Look who lost that one in the end,” Gonzalez said.

Comments

Welcome to The Banner's subscriber-only commenting community. Please review our community guidelines.