After the Trump administration fired her from a federal government job she loved, Caitlin Adams thought she might land on her feet working for the state of Maryland.

She’d had a promising interview in June with the Maryland Department of Natural Resources, answering Gov. Wes Moore’s call to fired federal workers to apply for open state jobs.

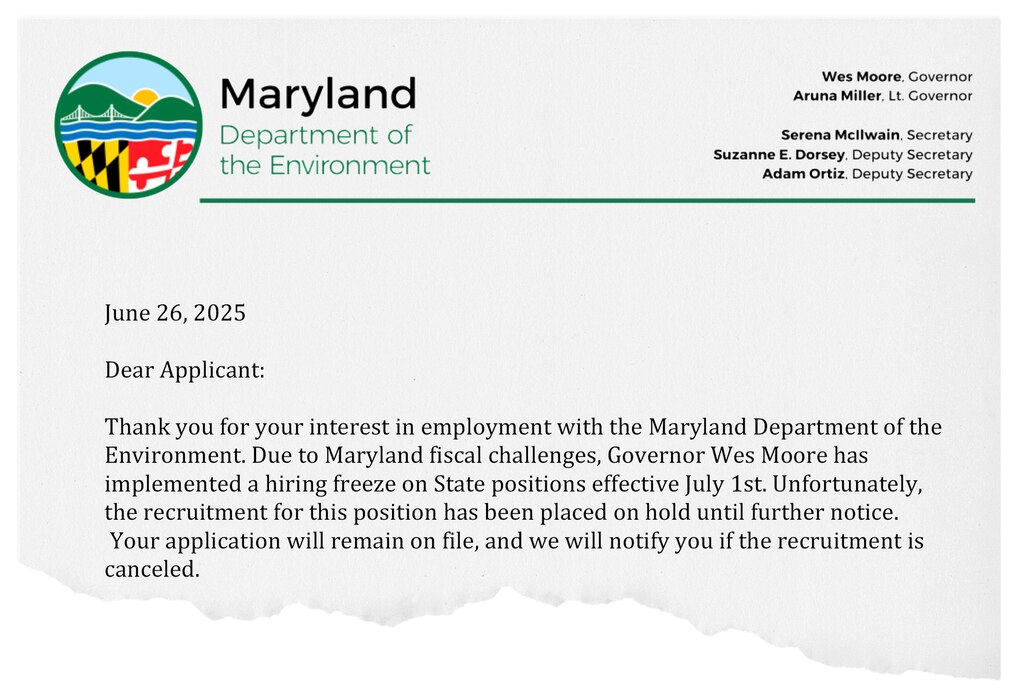

But a week later came a painful setback: Moore imposed a hiring freeze, and Adams learned the position she’d wanted was no longer available.

“This was the first hiring process that I’d actually made it anywhere,” said Adams, a Prince George’s County resident and former employee of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

As the Trump administration’s mass layoffs struck Maryland’s large federal workforce earlier this year, Moore publicly pressed state agencies to recruit displaced civil servants and fast-track their hiring. The federal government’s loss would be Maryland’s gain.

“In the Army, they teach you that if you get attacked, you don’t just sit there and take it. You mobilize,” the former Army captain said at a February news conference. “And in Maryland, this is our moment to mobilize.”

Read More

But Moore’s aggressive hiring efforts soon collided with the state’s harsh budget realities. The freeze, expected to last a year, is part of a plan to trim more than $100 million in salary costs. Lawmakers and Moore had settled on cuts during the legislative session, but Moore later decided how they would be carried out.

While hundreds of federal workers have found room in the state’s lifeboat, according to state officials, many others were left behind. Four current and former federal workers told The Baltimore Banner that they had been advancing through the state’s hiring process, only for the freeze to end their prospects.

One current federal employee said that while her job is safe, for now, she applied for lower-paying positions at the state comptroller’s office, hoping for a way out of an increasingly stressful work environment. She earned two interviews before Maryland’s hiring pause dashed her hopes.

“I was bummed out,” said the Frederick County resident, who requested anonymity for fear of retribution. “The governor had made a big deal about hiring feds that were being displaced.”

The employee said that she has applied for around 200 public and private sector jobs but often receives no response. Now, the state’s hiring freeze has left her feeling like she has even fewer options.

Employees who remain in the federal government “feel kind of captive,” she said. “They feel like they can’t really leave because the outside job market also just sucks.”

Though Moore promised expedited hiring, some federal workers said their applications languished for weeks or months in the state’s bureaucracy. Adams said her interview with DNR didn’t occur until two months after she applied.

Meanwhile, a former NASA engineer who requested anonymity for fear of retribution, was contacted in mid-May to schedule an interview with the Department of the Environment. From there, the process stalled until Moore announced the freeze. The interview never happened.

The Montgomery County resident said he hoped to work for the state even though it meant a 20% pay cut.

“I took a job that was in the federal service to serve my country, and I would have rather done that for the state than go work for a private company,” he said.

Many of the federal workers described themselves as Moore supporters and said they understood his need to act in response to a budget crunch. Still, the freeze was yet another blow in a demoralizing year, they said.

After losing his job with the Department of Health and Human Services, one fired federal employee, who requested anonymity for fear of retribution, said he applied to state jobs for their stability, benefits and option to telework.

He completed second interviews for two jobs at the state health department and was told he was a top candidate. Then the freeze brought all his applications to a halt.

The man said months of unemployment has forced him to live with his parents, sell his car and cope with anxiety and depression. His experience with the state was the latest in a string of disappointments.

“I can’t f-- win,” he said.

Moore’s February press conference came roughly five weeks before he and lawmakers knew how final budget negotiations would be settled, and well before he announced the freeze.

Meanwhile, the job applications flowed in.

As of April 17, the state received 20,000 applications from more than 6,800 separated federal workers, and in the last seven months hired 349 of them, according to the Moore administration.

Lauren Molineaux was one of the lucky ones. The Howard County resident’s skill set from working in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services translated over to what she considers her “next dream job” at Maryland’s Department of Human Services.

D.C. resident Neal Desai voluntarily left his job at the Office of Personnel Management in January, just after the Trump administration took office. He said he just knew the federal workforce “was in for a hard time” and that he is “deeply committed” to nonpartisan civil service.

In March, Desai, 41, landed a new job as Maryland’s chief human resource officer, responsible for all things personnel for the state — benefits, payroll management and employee relations.

The transition was “bittersweet,” he said, adding that working for the state of Maryland has been “wonderful.”

Moore spokesperson Carter Elliott IV said in an email, “Maryland has been unwavering in its commitment to its federal workers.”

Hiring them, he said, was one of many ways the state planned to help, including job fairs and unemployment assistance.

The governor has made clear from the beginning there were not enough open jobs for every federal worker, but, Elliott said, the administration “is committed to using every tool in its arsenal to help our public servants.”

Like many other former federal employees, however, Adams is still looking for work.

In the environmental field, federal layoffs have flooded the market with qualified, experienced candidates, while funding cuts have made job opportunities increasingly scarce.

The uncertainty has forced Adams to consider leaving her career behind.

“I’ve kind of thought, well, if nothing happens by September, then I’ll start applying to truly anything that will pay the bills,” she said.

Comments

Welcome to The Banner's subscriber-only commenting community. Please review our community guidelines.