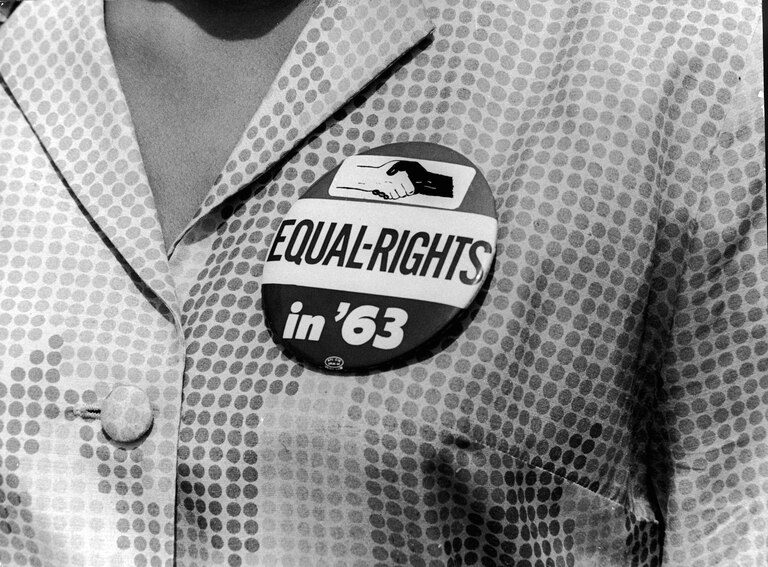

For the people of Baltimore who were caught up in post-World War II civil rights struggles, Aug. 28, 1963, was an embarrassment of riches that, for some, required a tough choice.

On that date, after a decade of increasingly tense challenges to the “whites only” admissions policy at the Gwynn Oak Amusement Park in Baltimore County, the protesters could claim victory. In The Baltimore Sun, headlines went from “283 Integrationists, Many Clerics Are Arrested At Gwynn Oak Park” (July 5, 1963) to “Gwynn Oak To Be Integrated Aug. 28″ (July 20, 1963). That was also the date of a long-planned March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in Washington, D.C. Some people had to make the choice: D.C. or Baltimore County?

This was a history-making day of triumph at both places. An 11-month-old Black girl in the arms of her father on a merry-go-round led a mostly peaceful day at the amusement park. In Washington, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. went off script and ad-libbed with words previously delivered in bits and pieces in other settings. Now those words are seemingly preserved in amber to be extracted and manipulated to fit the needs of the moment: “I have a dream,” King said.

People enjoyed the amusement park until it closed for good in 1974, but King began rethinking that dream within a matter of days.

Those whose reverence for a snippet of the speech propels them to commemorate its 60th anniversary generally know five things about King: He led the Montgomery, Alabama, bus boycott that began in December 1955 and lasted for more than a year. He had a dream that he so powerfully articulated on Aug. 28, 1963. He won a Nobel Peace Prize in 1964. He was assassinated on April 4, 1968. He was honored with a federal holiday in 1983.

What’s left out is the inconvenient truth: Three weeks after the speech, he was back in Alabama — in Birmingham (aka “Bombingham”) — presiding over the joint funeral of three of the four girls who died when cowardly racists bombed the 16th Street Baptist Church on the Sabbath three days before. To him, the dream had become a nightmare that day, and the girls were “the martyred heroines of a holy crusade for freedom and human dignity.”

“They have something to say,” King said of the girls in his eulogy on Sept. 18, 1963. Their message was for “every minister of the Gospel who has remained silent behind the safe security of stained-glass windows,” “every politician who has fed his constituents with the stale bread of hatred and the spoiled meat of racism,” “a federal government that has compromised with the undemocratic practices of Southern Dixiecrats and the blatant hypocrisy of right-wing northern Republicans,” and “every Negro who has passively accepted the evil system of segregation and who has stood on the sidelines in a mighty struggle for justice.”

“They say to each of us, Black and white alike, that we must substitute courage for caution. They say to us that we must be concerned not merely about who murdered them, but about the system, the way of life, the philosophy which produced the murderers. Their death says to us that we must work passionately and unrelentingly for the realization of the American dream.”

From that time until near the end of his life, King spoke of the nightmare that his dream had become, evident in the church bombing, his campaigns against Northern racism in cities like Chicago, his crusades against poverty in Appalachia, and in his antiwar efforts that were partly rooted in wanting the nation to focus on social justice at home. In a sermon at his Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta on July 4, 1965, he said: “I must confess to you this morning that since that sweltering August afternoon in 1963, my dream has often turned into a nightmare.” And in an interview broadcast on NBC on May 8, 1967, he said: “I must confess that the dream that I had that day has at many points turned into a nightmare. … I’ve come to see that we have many more difficult days ahead and some of the old optimism was a little superficial and now it must be tempered with a solid realism.”

The realism that he expressed at the end of his life was there in the speech that he gave on the Mall 60 years ago, in that part of the speech that failed to hit the notes that would resonate with the crowds the way a James Brown groove could, the part of the speech that led the great gospel singer Mahalia Jackson to whisper to him to shift to a different key: “Tell them about the dream, Martin.” And with that cue, he did.

Up to that point, he had focused on how America was in default. As King saw it, the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution formed “a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir” and President Abraham Lincoln’s 1863 Emancipation Proclamation extended that to “millions of Negro slaves who had been seared in the flames of withering injustice.”

Since that time, he said, “America has defaulted on this promissory note insofar as her citizens of color are concerned. Instead of honoring this sacred obligation, America has given the Negro people a bad check, a check which has come back marked insufficient funds.”

He demanded that the nation urgently address police brutality, government-sanctioned segregation and the denial of the right to vote to Black people — issues that were ultimately within the purview of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

The last year of his life was bookended by an antiwar speech in New York City on April 4, 1967, and a prophetic last speech on April 3, 1967. His focus was not on a kumbaya dream repurposed today by politicians and faith leaders who are antithetical to a present-day social-justice agenda that is remarkably like King’s.

“1963 is not an end, but a beginning,” King said in the overlooked part of the speech on the Mall in Washington. To truly commemorate what happened in 1963, recall all that King said about a dream on Aug. 28 and what he said from Sept. 18, 1963, to April 3, 1968. He constantly prodded the government to honor its promissory note and urged everyone to do what they could individually to assure that each of us shares “the riches of freedom and the security of justice.”

E.R. Shipp is a veteran journalist and Pulitzer Prize-winning columnist. She is also currently an associate professor at Morgan State University.

Comments

Welcome to The Banner's subscriber-only commenting community. Please review our community guidelines.