The grass was a green, green ribbon, bright under a May afternoon sun and punctuated by rows of white headstones descending a softly rolling hill.

Most days it’s lonely at the Annapolis National Cemetery, and Sunday was no exception. I was looking for four particular graves, and it can take time to decipher the numbers carved into ancient marble marking the right spot. Solitude helps.

Then, suddenly, they were in front of me. There was Mary J. Dukeshire, first among them buried here after dying on July 11, 1863 — just weeks after a corps of about 30 nurses was set up at the massive Civil War hospitals in Annapolis.

Rachel Spittle arrived next, in August, followed by Hannah Henderson and Mrs. J. Broad in October. These are women who helped reinvent the idea of a “nurse” and then were so quickly gone — dead, buried and almost forgotten.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

“They were coming from all over,” said Mike Fitzpatrick, an Annapolis historian writing a book about the city during the Civil War. “You have to realize there was no nursing profession, and what qualified as a nurse could be anything from a woman who comes in once for her son in the hospital to a woman who is employed by the Army and works for several years.”

Memorial Day weekend is that rare time of year when Annapolis National Cemetery has lots of visitors, and a ceremony is set for Friday. The holiday was created to honor the Civil War dead, such as by leaving flowers at graves, and has evolved into the moment when we turn our attention to the remembrance of final sacrifice in all our wars.

This is a place where quiet is more than the absence of sound. It is a place where the stories of lives slowly fade away, like the carvings on stone that’s more than a century old.

For Mary, Rachel, Hannah and Mrs. Broad, it shouldn’t be that way. We should celebrate their stories not just on Memorial Day, but every time we talk about duty and service.

There are plenty of clues as to who they were and how they spent their final days. The Civil War started in 1861, as Southern states began seceding from the Union after the election of Abraham Lincoln. A Massachusetts militia rushing to the defense of Washington was detoured to Annapolis by a mob in Baltimore.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

The Army stayed in Maryland’s capital city until after the end of the war in 1865. Annapolis was a crossroads for Union troops heading to battlefields and returning after being wounded or taken prisoner.

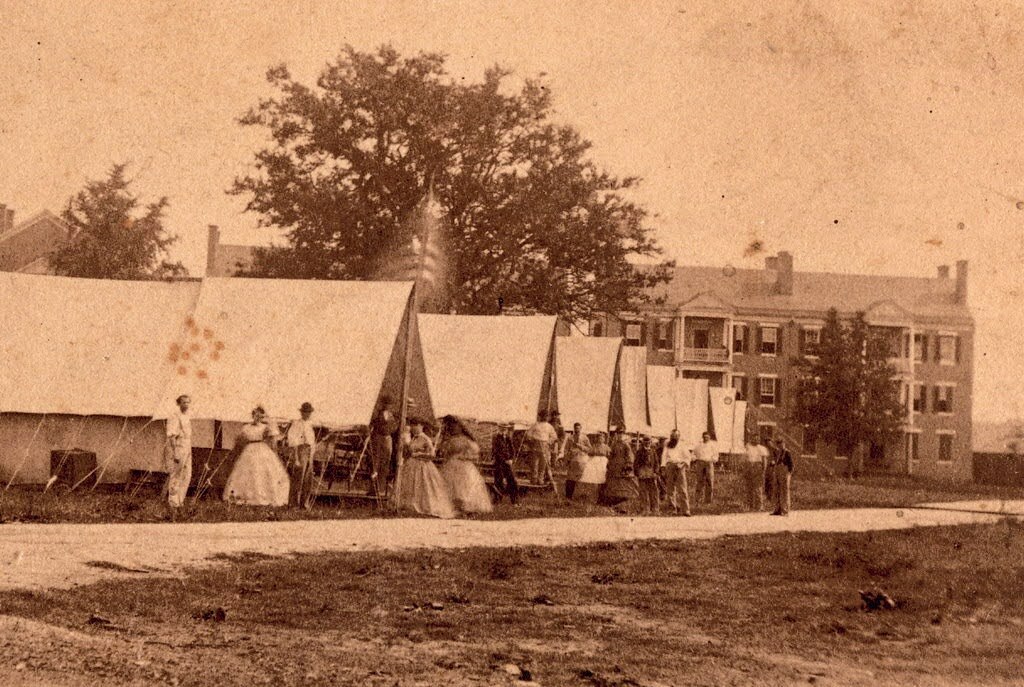

The Army set up four hospitals in Annapolis during the war, caring for thousands of wounded, sick and dying men on the Naval Academy grounds; at St. John’s College; at Horn Point in Eastport; and in Parole, an area named for the prisoner exchange program during the war. The war coming to Annapolis made the sleepy little city a noisy, muddy, crowded and violent place.

“Annapolis … had an excellent opportunity to perceive the demoralization and brutalization of war,” wrote Samuel W. Brooks, an aide to the governor who believed he was the only state official left in the city during much of the war. “Men who had evidentially come from refined homes and been accustomed to modern comforts soon lost all sense of decency and their vulgarity and coarseness were almost indescribable. Murders became an almost everyday occurrence. Human life was held in the greatest contempt and homicides ceased to attract attention.”

Passing into a city — which a private from Rhode Island stuck in Annapolis called “The no God town” in a letter to his parents — came roughly 30 women intent on helping.

Dr. Bernard A. Vanderkieft, a Dutch naval surgeon who immigrated to the United States and immediately joined the Army, began work in Annapolis in June 1863. He ran the field hospital at bloody Antietam 90 miles away, near Frederick, and when the Army reorganized its medical corps, he was named supervising surgeon of U.S. General Hospital Division No. 1 at the academy and the disease hospital in Eastport. One of his first changes was adopting a new idea in medicine and creating a group of women nurses, including his wife, Josepha.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

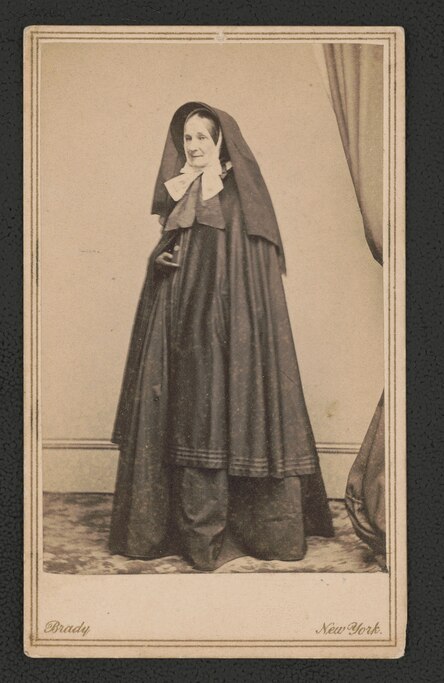

“There was no formal training,” Fitzpatrick said. “Dorothea Dix, who was the de facto chief of the Army’s nursing corps, didn’t want a bunch of young, pretty women coming in and flirting with the soldiers. Mostly these women, the hardcore nurses, were motherly women or at least spinsterly women usually over the age of 30 who volunteered or were paid to come in.”

Many lived together in an Annapolis boarding house under the supervision of Adeline Tyler, a Massachusetts woman who after being widowed studied in the same German school as British nursing pioneer Florence Nightingale. She ran an Episcopal infirmary in Baltimore and then drifted on the tides of war until landing in Annapolis to work with Bernard Vanderkieft.

Annapolis nurses under Tyler focused on the preparation of food by hired cooks, reading to patients, writing letters for them — and writing their families when they died. Overcrowded, unsanitary conditions and a flow of dying men released from the notorious Confederate prison in Andersonville, South Carolina, led to waves of typhus, smallpox, typhoid and diphtheria sweeping across Annapolis.

“Three Transports brought us last week a large number of sick — a fourth arrived to-day — bringing however, but few to the hospital — Still another boat is expected in a day or two … Many of the new patients have died — and, nearly all, of Typhoid Pneumonia,” Adeline Walker of Portland wrote a friend on April 14, 1863 in a letter posted on the Maine Memory Network. “Four out of the nineteen received into Miss. Quinby’s wards have died — six in Mrs. Gray’s wards none in mine as yet — but some are very sick — One has a deep Sabre-cut in his head & erysipelas — is very low to-day — He belongs to 1st Vermont Cavalry — was wounded at Drainsville, Va There are six bodies in the deadhouse now —the dead are kept there but one night.

“Most of the men are suffering more or less, with diseases of throat or Lungs so the nice woolen under clothing you sent comes just in time — I shall distribute many of the garments immediately to those who need them much — Wish you could hear all the fine things said about your beautiful Union Quilt.”

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

Fitzpatrick believes nine nurses in all died in Annapolis. The first may have been volunteer, Catherine Brewer of Annapolis. After caring for soldiers at the Naval Academy hospital and taking clothing and blankets to the prisoner exchange camp in Parole, she died on Nov. 12, 1862. Two of her sons fought for the Union, while the third joined the rebels.

Mary was the first buried under a wooden cross in the cemetery created on land sold to the Army by Catherine’s husband, local judge Nicholas Brewer. The three other women were buried that summer and fall.

Tyler, who was exhausted by her work and went home, was replaced by Maria Hall. She was a battlefield nurse who had cared for one of Abraham Lincoln’s young sons and remained in Annapolis for the rest of the war.

Then Mary A.B. Young joined the dead on Jan. 12, 1865.

“She wanted to be buried with the boys,” said Fitzpatrick, who has an extensive collection of letters and photos from Annapolis during the war.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

Her roommate, Rose M. Billing, followed two days later. Her family retrieved her body. Amanda Kimball went next on Feb. 14, and also was relocated.

Five months after Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee surrendered at Appomattox, Josepha died of something she contracted from the dwindling number of patients. Her husband, the surgeon, left the Army and died near the first anniversary of her death.

“It was probably typhus, that was the most common disease but any of those things could have killed them,” Fitzpatrick said.

But as the other nurses went home, either to graves close to loved ones or to live out their lives, Mary, Rachel, Hannah and Mrs. Broad stayed behind in Annapolis.

Did their families respect their wishes to be buried with the boys? Were they widows or spinsters with no one to claim them?

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

The important thing, now, is to make sure they are not forgotten. It’s up to us to remember them beyond Memorial Day.

Comments

Welcome to The Banner's subscriber-only commenting community. Please review our community guidelines.